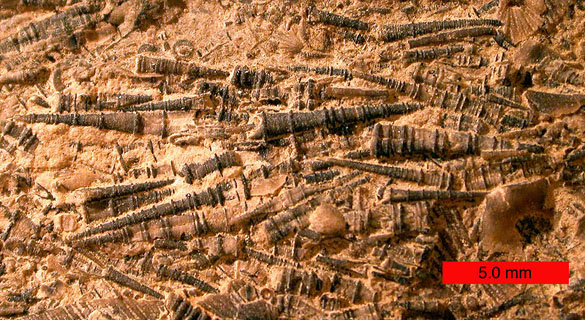

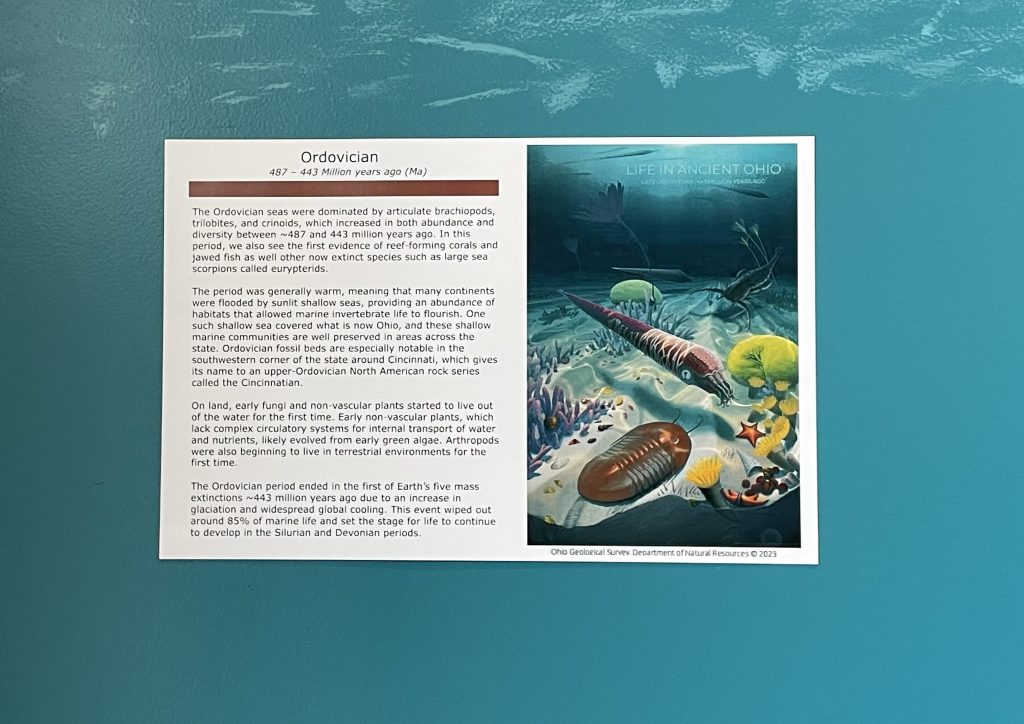

It was my privilege to join an Estonian-Polish-Chinese-American team interpreting partial soft-tissue preservation of the feeding devices of Silurian cornulitids, which are extinct Paleozoic organisms that constructed small conical, ribbed tubes. Cornulitids are very common sclerobionts (hard-substrate dwellers) in the Upper Ordovician Cincinnatian Group of Indiana, Kentucky and Ohio, so these are familiar fossils to Wooster geologists. Now we know a little bit more about their paleobiology. Our new paper can be downloaded here.

It was my privilege to join an Estonian-Polish-Chinese-American team interpreting partial soft-tissue preservation of the feeding devices of Silurian cornulitids, which are extinct Paleozoic organisms that constructed small conical, ribbed tubes. Cornulitids are very common sclerobionts (hard-substrate dwellers) in the Upper Ordovician Cincinnatian Group of Indiana, Kentucky and Ohio, so these are familiar fossils to Wooster geologists. Now we know a little bit more about their paleobiology. Our new paper can be downloaded here.

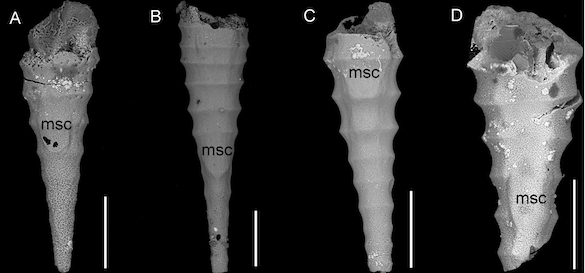

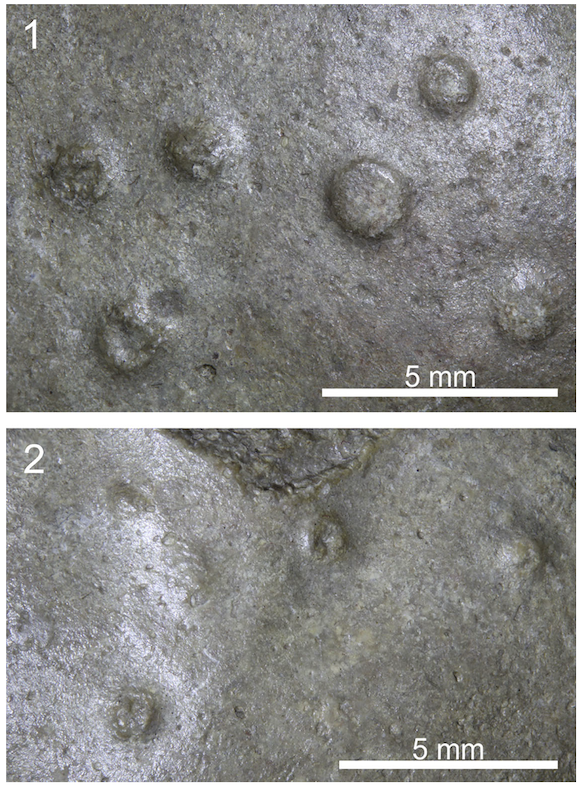

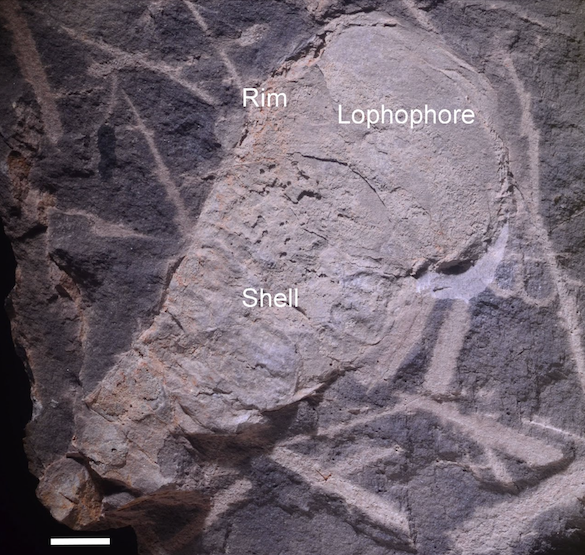

The top image is from Figure 3A of Vinn et al. (2026). It is Cornulites cf. cellulosus (HWR007a) showing a fully protracted likely lophophore (filter-feeding device). Scale bar is 5 mm.

Abstract.–Circular structures observed at the apertures of several Cornulites specimens from the earliest Silurian of China are interpreted as possible fossilized remains of a lophophore with a simple, ring-like morphology. These structures may represent partial preservation of the feeding apparatus, with the absence of tentacle preservation likely resulting from taphonomic processes. The preserved rim surrounding the circular structure likely reflects the thickness of the lophophore and its tentacles, while a neck-like extension visible in one specimen is interpreted as the basal region of the lophophore. Specimens displaying a partially extended lophophore suggest that Cornulites individuals may have been capable of retracting their lophophore entirely into the shell, between feeding episodes, although complete retraction remains speculative. These partial soft-tissue remains support the classification of cornulitids as lophophorates. However, the available evidence remains insufficient to definitively resolve whether cornulitids are more closely related to bryozoans or phoronids. As the only shelled benthic fossils in the Huangshi deposits, cornulitids seemed to have been opportunistic organisms which were able to colonize and thrive in oxygen-deficient palaeoenvironments following the Late Ordovician mass extinction.

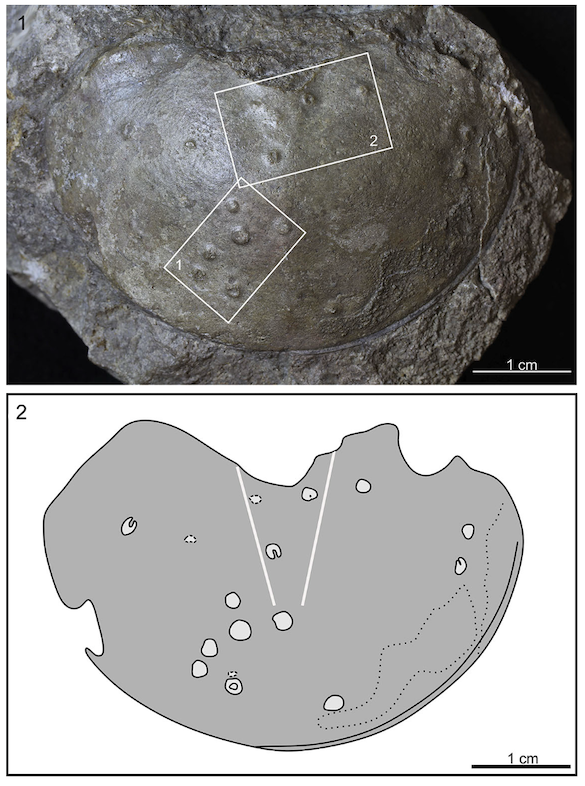

From Figure 4 of Vinn et al. (2026). Cornulites sp. (specimen HWR072a-1) interpreted as showing a partially retracted lophophore. Scale bar is 5 mm.

From Figure 4 of Vinn et al. (2026). Cornulites sp. (specimen HWR072a-1) interpreted as showing a partially retracted lophophore. Scale bar is 5 mm.

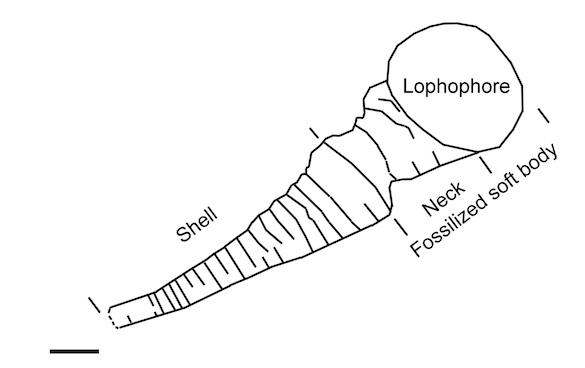

From Figure 5 of Vinn et al. (2026). Schematic line drawing of Cornulites cf. cellulosus (HWR007a) showing a fully protracted lophophore. Scale bar 5 mm.

From Figure 5 of Vinn et al. (2026). Schematic line drawing of Cornulites cf. cellulosus (HWR007a) showing a fully protracted lophophore. Scale bar 5 mm.

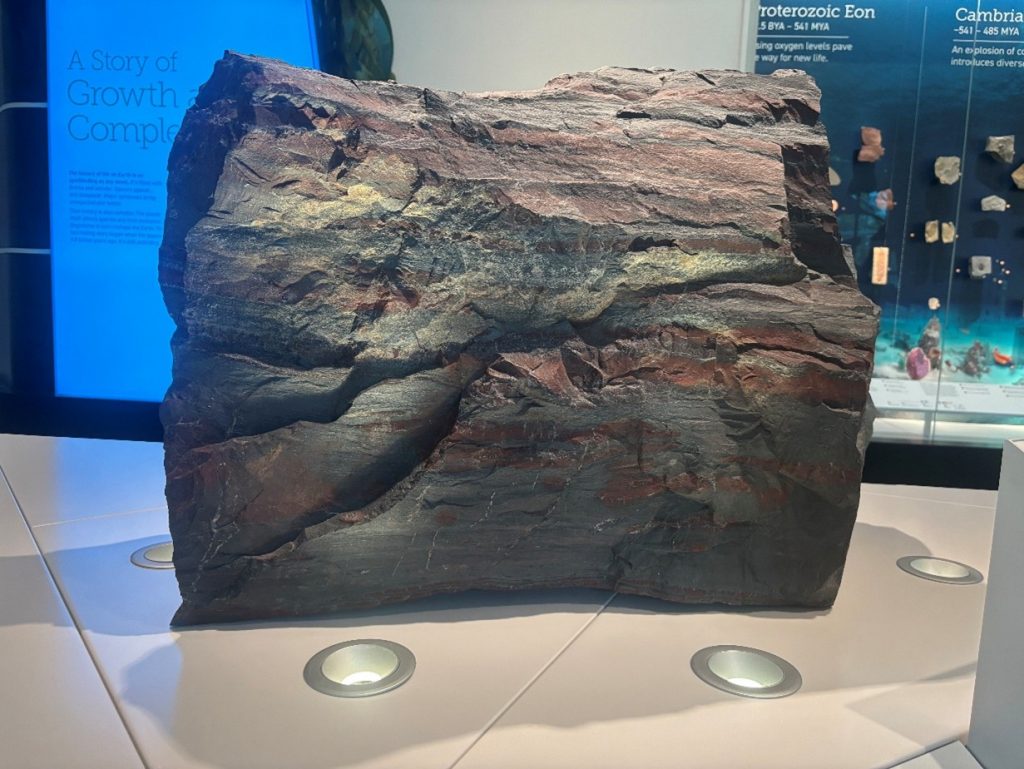

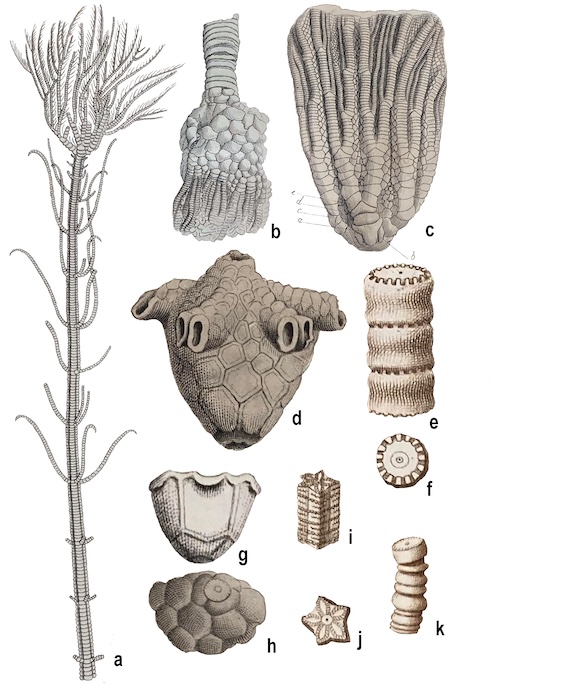

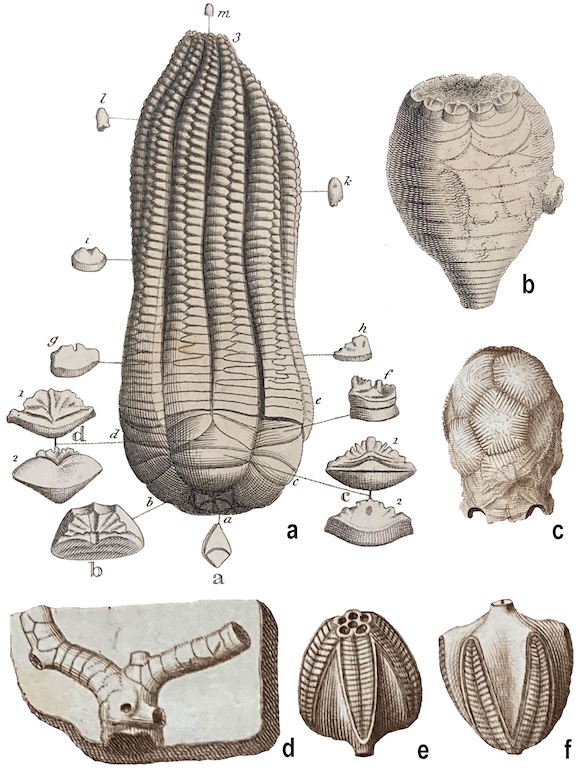

Cornulitids are old friends to those Wooster geologists who studied Ordovician fossils in paleo courses. This is the genus Cornulites Schlotheim 1820, specifically Cornulites flexuosus (Hall 1847). It was found in the Whitewater Formation (Late Ordovician, Katian) during a College of Wooster field trip to southeastern Indiana (C/W-148; N 39.78722°, W 84.90166°).

Cornulitids are old friends to those Wooster geologists who studied Ordovician fossils in paleo courses. This is the genus Cornulites Schlotheim 1820, specifically Cornulites flexuosus (Hall 1847). It was found in the Whitewater Formation (Late Ordovician, Katian) during a College of Wooster field trip to southeastern Indiana (C/W-148; N 39.78722°, W 84.90166°).

I thank my international co-authors for inviting me to join this team.

Reference:

Vinn, O., Zong, R., Wilson, M.A., Liu, Y. and Zatoń, M. 2026. Partially preserved cornulitid feeding apparatuses from the lowest Silurian of South China support the lophophorate affinities of this enigmatic group. Lethaia https://doi.org/10.18261/let.59.3

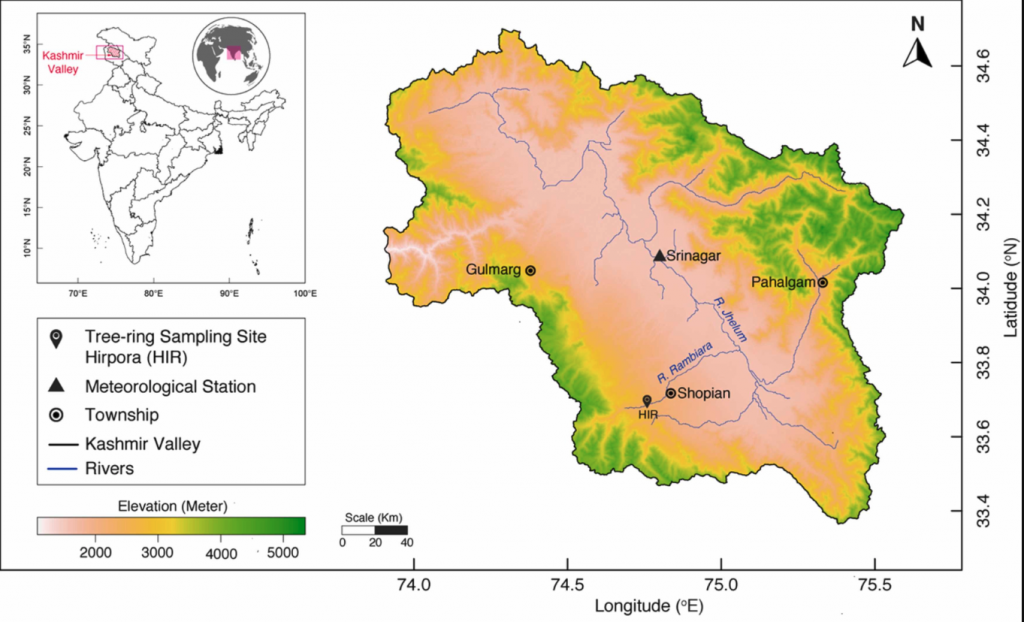

The Weather station active in the Arboretum since the late 1800s provided the monthly climate records.

The Weather station active in the Arboretum since the late 1800s provided the monthly climate records.