Guest Blogger: Lynnsey Delio, The Keck Geology 2025 team has been working in the Wooster dendrochronology lab for the first week of research. The team cored the oak tree in front of Scovel on day 1 for some practice coring. They also made use of the woodshop in Scovel Hall and practiced sanding and mounting cores.

Dexter, Lynnsey, Lev, and Landon coring the oak tree in front of Scovel Hall.

Lev with a core reveal!

The team has also been working with programs COFECHA and CooRecorder in the computer lab to mark the tree rings on red cedars from Southeast Alaska. They have been working to create an optimized red cedar tree ring series for the area, dating back centuries. This data can be used to compare to other tree ring series and look for climate signals and responses. These climate responses can be analyzed from a global climate perspective to understand the correlation between dendrochronology and global climate phenomena.

To accurately date the cedar cores, the team used cores from previously dated red cedars from Klawock, Southeast Alaska to correlate them to the undated samples. Some of these previously dated cores included logged trees that were intended for use in totems.

The team and Nick in the computer lab working with the dendrochronology programs.

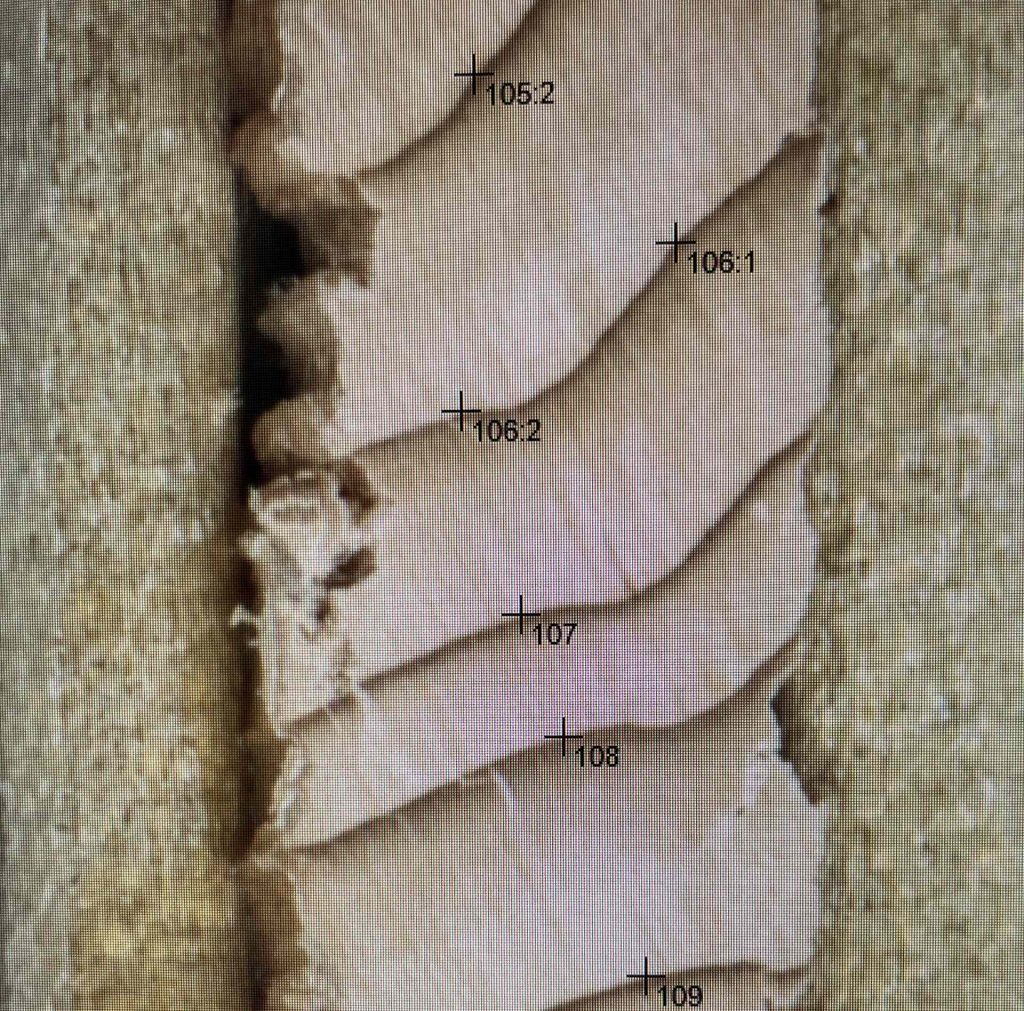

A close-up of one of the red cedars marked using CooRecorder.

Some of the oldest red cedars in the area were taken from dead trees. Red cedars are naturally rot-resistant and can stand dead for centuries. Because of this, the Keck team actually dated a core with an inner ring date of CE 1130. Dating this far back in history will give our team and others access to climate information far beyond the observed record.

During one of the cooler days of the week, the team piled into Nick and Dr. Wiles’ cars for an afternoon in Wooster Memorial Park. There, they got lots of practice coring the hemlocks in the park.

The team watching as Nick explains the wonderful art of coring trees.

Lev and Nick taking a core from “Big Boy.”

Landon with a boulder as Dr. Wiles takes a detour from dendrochronology and explains the geomorphology of Wooster Memorial Park.

The team testing out their boots before venturing into the Alaskan rainforest (they work!).

The link to the full publication and supporting data can be found

The link to the full publication and supporting data can be found

Diatom-derived highly branched isoprenoids (HBIs) are lipid bio- markers found in marine and lacustrine sediments. Most of the work on these has been done in marine environments and the UC group is now extending study to lake settings.

Diatom-derived highly branched isoprenoids (HBIs) are lipid bio- markers found in marine and lacustrine sediments. Most of the work on these has been done in marine environments and the UC group is now extending study to lake settings. The sampling team on a North Dakota Lake.

The sampling team on a North Dakota Lake. Locations of the 50 lakes sampled in this study (A) and expanded maps of the Indiana lakes (B) and Adirondack region lakes (C).

Locations of the 50 lakes sampled in this study (A) and expanded maps of the Indiana lakes (B) and Adirondack region lakes (C).

Students sampling the remanent white oak stand at Browns Lake Bog a site managed by the Nature Conservancy.

Students sampling the remanent white oak stand at Browns Lake Bog a site managed by the Nature Conservancy.  Coring the second-growth white oaks in Wooster Memorial Park.

Coring the second-growth white oaks in Wooster Memorial Park.

The College of Wooster campus maintains an impressive stand of old growth white oaks on its campus. Here members of the Holden Arboretum Tree Corps sample one the the impressive old trees.

The College of Wooster campus maintains an impressive stand of old growth white oaks on its campus. Here members of the Holden Arboretum Tree Corps sample one the the impressive old trees. Secrest Arboretum (on the Wooster campus of the CFAES) is one of our favorite sites to cores trees. Many of the trees from all around the world have lived in Ohio for over 100 years. Here one of the coauthors cores a white oak planted about 100 years ago.

Secrest Arboretum (on the Wooster campus of the CFAES) is one of our favorite sites to cores trees. Many of the trees from all around the world have lived in Ohio for over 100 years. Here one of the coauthors cores a white oak planted about 100 years ago.

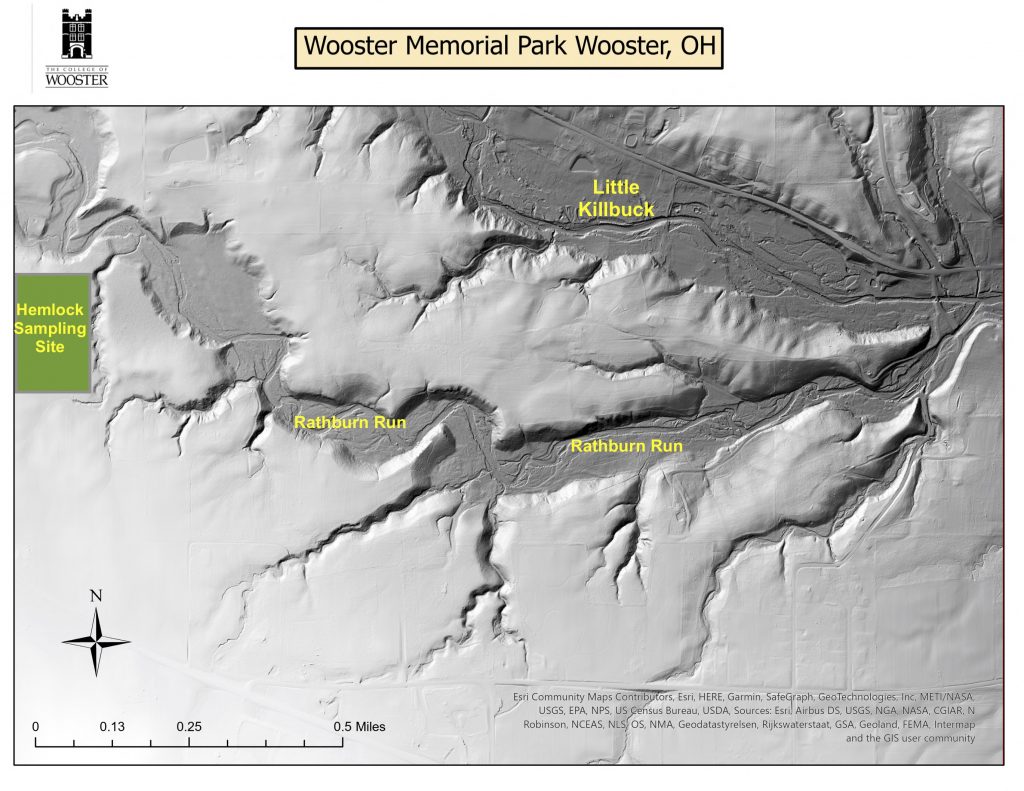

Lidar Map of Wooster Memorial Park – the green field in the west of the park is the approximate location of tree-ring sampling.

Lidar Map of Wooster Memorial Park – the green field in the west of the park is the approximate location of tree-ring sampling.