Guest Bloggers SEAK25 (Keck – Southeast Alaska 2025) – Dendrochronological methods are a key part to our research team’s success. While analyzing and drawing conclusions from data is essential, it is equally as important to ensure the proper collection, preparation, and handling of samples and extraction of ring measurements. There are many key steps to this process in dendrochronology, that when done correctly, ensures the success of a research team.

Taking samples

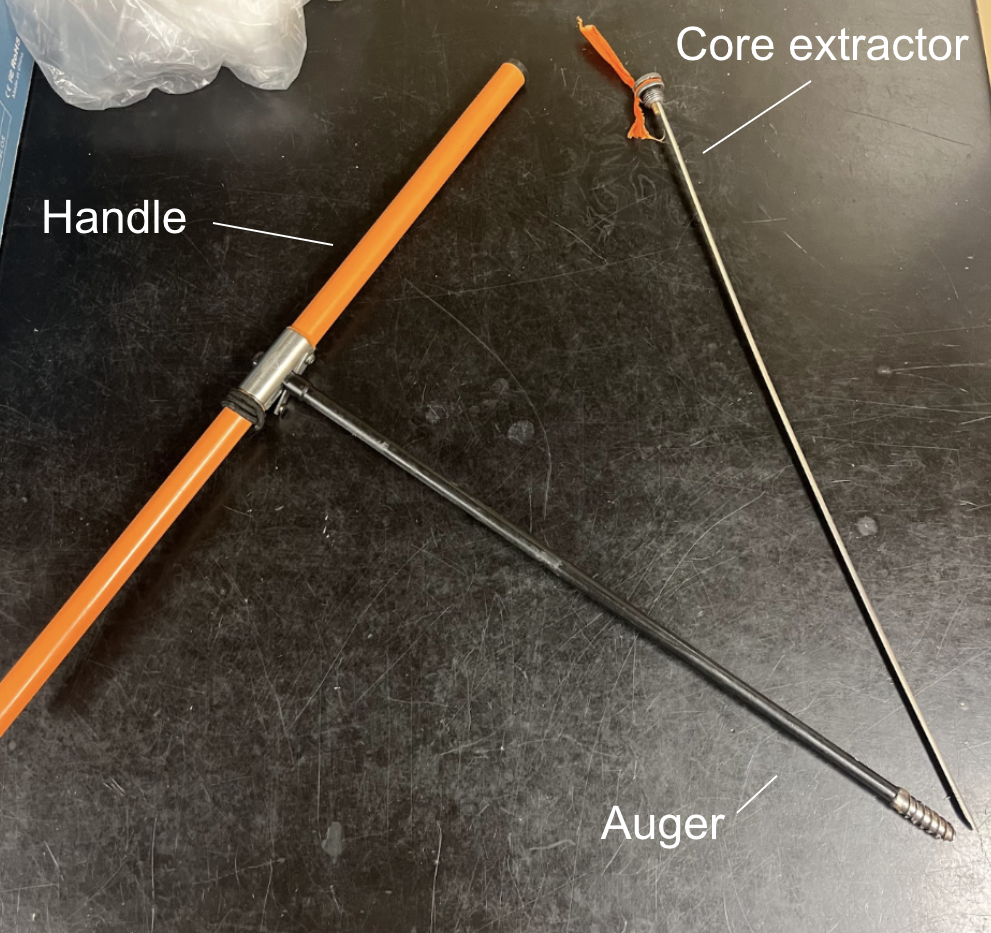

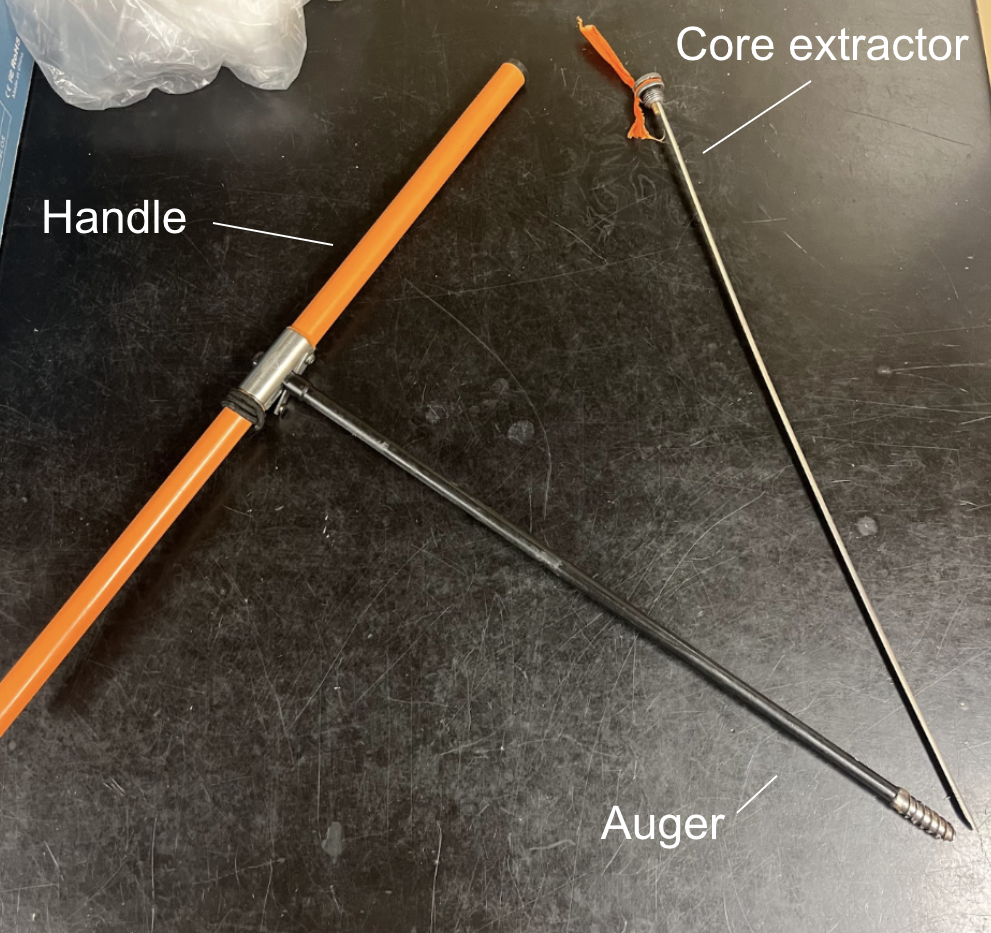

Tree cores are extracted using an increment borer. By manually drilling the auger into a tree, the core is preserved inside the increment borer with minor injury to the tree. The core extractor, a half circular metal tray, then fits into the auger bit. After cranking the handle counter clockwise, the core then fully separates from the body of the tree. Pulling the core extractor out of the auger allows the extraction of a tree core.

Increment borer.

Selecting the right tree within a stand is crucial to obtaining a good sample. It is important to consider factors such as tree health and direction of lean before coring. Trees that lean excessively can be more difficult to core, as the wood is under more directed pressure. We aimed for trees that stand tall, with little to no lean. If there is a slight lean, then we cored perpendicular to the direction of the lean. When coring we were sure that the auger aimed to the heart of the tree and did not enter at an angle. Depending on the thickness of the tree, two separate cores are required to get data on the entire diameter of the tree. Smaller trees may only require one coring through the full diameter.

Storing and labeling samples

After extracting cores from trees, samples must be properly stored and labeled. The cores are carefully removed from the extractor tray of the increment borer storing the in a plastic straw. It is important to keep the end of the straw near the opening of the auger to ensure the entire core is preserved in case the core itself is broken and is extracted in multiple pieces. Once the sample is safely inside of the plastic straw, the straw ends are folded in to keep the sample in place. The plastic straws we use have holes throughout for proper drying of the sample.

Plastic straws used for sample storage.

It is critical to label the samples immediately after putting them in the plastic straw to avoid mislabeling and confusion. Samples are labeled by their tree ID. This tree ID is given based on research location and sample number. The red cedar cores from Klawock, Alaska were from the “Lower Steelhead” site. They were marked with the label LSRC, standing for “Lower Steelhead Red Cedar.” Each tree from the site was assigned a number as it was cored,;LSRC01 was the first tree cored. The label is written directly on the plastic straw to keep the samples organized. Assuming there are two cores from each tree, each core should have both an “A” and “B” sample, taken from opposite sides of the tree. If they are stored in separate straws, “A” or “B” should be written after the tree ID (eg. LSRC01 A). If it is not clear which end of the core is which, labeling the inside “pith” could also be helpful for future analysis. Tree IDs are used during the marking and cross dating process to identify particular cores, so accurate identification is important.

Once the samples are labeled and stored in the straws, they can be taken back to the lab where they will air dry inside of the plastic straw for anywhere from a couple days to several weeks. Having a fully dried core will lessen the likelihood of warping or cracking when it is glued to a mount.

Prepping core samples for analyses

Once the cores have been dried, they are placed in wooden core mounts. Cores are glued into the mounts with the grain of the wood oriented vertically. The cores are then secured using tape every 2 to 3 inches. The mounts are then labeled with the sample name. Once the samples are mounted they are ready to be sanded. This process begins with placing the core upside down on the belt sander. The core is first belt sanded on 80 to 150 grit then 180 to 220 grit. The cores should be sanded approximately to the thickness of a quarter above the line of the wood mount. The samples are then hand sanded depending on the softness of the type of wood. For example, yellow cedar is harder than red cedar so it was hand sanded using 600 grit then 800 grit sandpaper. Red cedar is softer so it was hand sanded with 800 grit.

Mounted and labeled cores.

A sample after being belt sanded.

Scanning samples

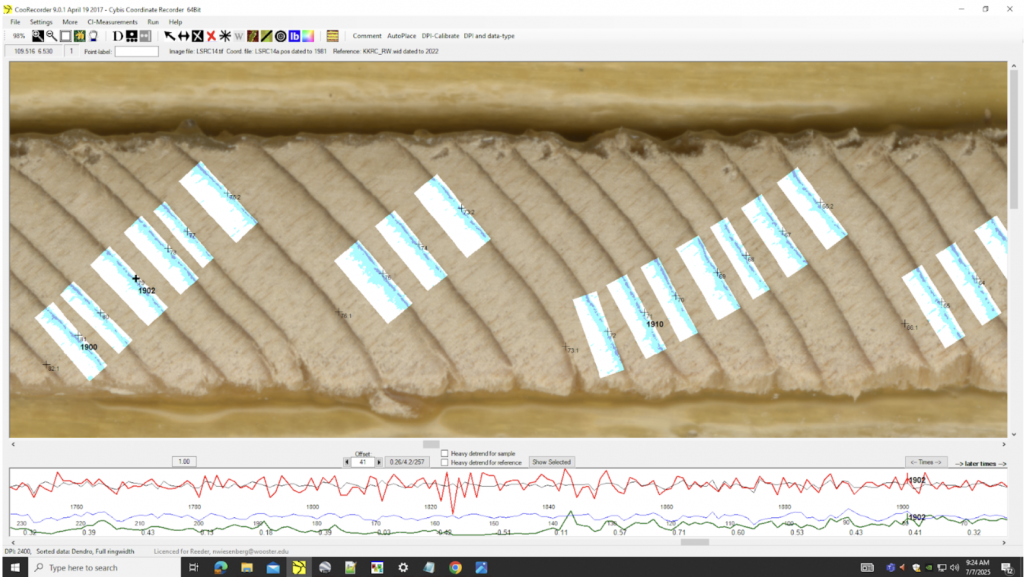

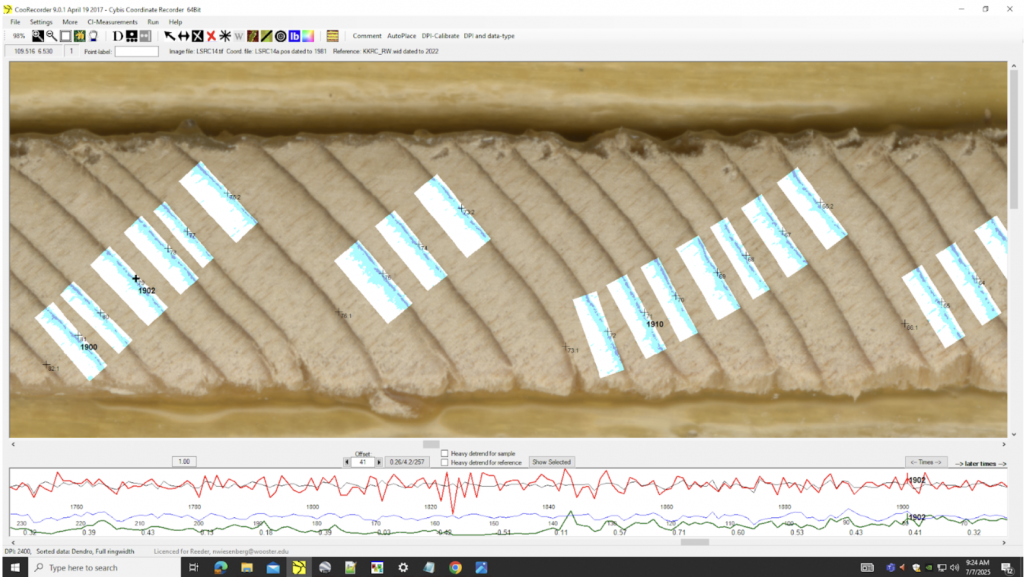

Once the sanding process was completed, and the wood anatomy was clear and scratches were removed the cores are ready for scanning. We used a flatbed photo scanner to scan the cores (2400 dpi). The scanned images were then uploaded to CooRecorder, a software used for tree-ring dating and analysis (Maxwell and Larsson, 2021). CooRecorder allows users to click and place a point on the boundary between each ring, capturing annual layers within a tree. We placed points on the earlywood-latewood boundary, capturing the end of each growing season. This boundary can be identified by the distinct changes in color between latewood and earlywood, latewood being tighter-grained and darker than the more porous and lighter-colored earlywood. We then measured the distances between ring boundaries (individual ring thicknesses). A master ring-width chronology of red cedars already in hand from the area (our master chronology) was used as a dating reference. Given that cores we measured and the series in the mater chronology were from the same region and experienced the same climate signals, we expected the widths to match to some extent. This is an an important step in recognizing any mistakes in dating or any unusual growth in the trees. The CooRecorder software can also display the latewood blue intensity, which is shown in the image below (a subject for a later blog post, blue intensity is a fascinating parameter that we are excited to analyze later this week). The final step for each core was ensuring the latewood blue boxes were parallel to the ring thus accurately representing the boundaries of each ring. Overall, the dating using CooRecorder is a tedious yet rewarding process, and upon completion, we had dates and ring-width measurements for each core and could proceed to chronology development.

Screenshot of the CooRecorder software with the latewood blue intensity parameter turned on.

Quality Control of the Cross dating

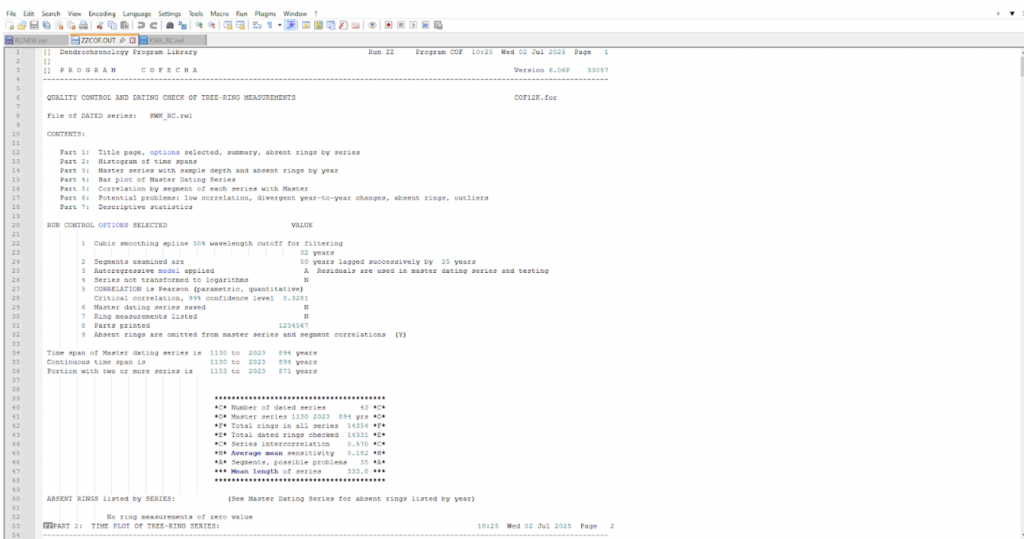

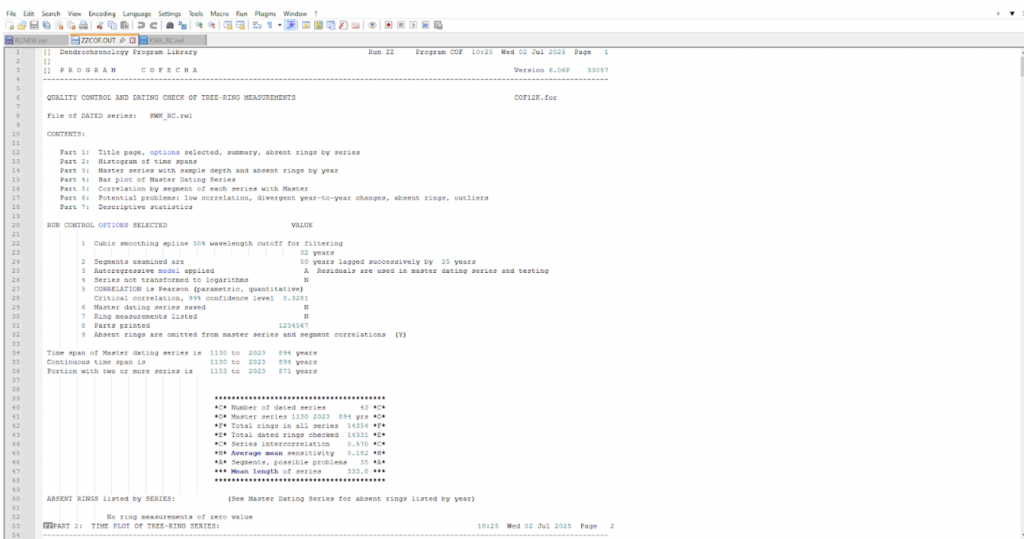

Another important step in the dendrochronological process is the building of a “master” chronology. A master chronology is a collection of tree ring series of a particular species that is generally accepted to be a reliably dated and can be compared with newly measured ring – width series. In our case we added to the master chronology which was then used to evaluate the climate signal in the trees.

An example run that compared two of our Western red cedar chronologies, using the COFECHA program (Holmes 1983).

For example, an existing Western redcedar master chronology may be used to check the reliability of a different red cedar chronology from a similar area. This is accomplished by comparing the relative growth of the trees over time. If the chronologies display a similar growth pattern as measured by correlations (i.e. years of faster and slower growth are during similar years), then the new chronology can likely be trusted as being a well-dated and potentially useful dataset. This process of cross-referencing an existing chronology with a new one is called cross dating, and is an important principle in dendrochronology. Our research team has built a new master chronology for Western redc edars using the program COFECHA (Holmes, 1983) that consist of 60 ring-width series. To our knowledge, this is the most robust and complete chronology of red cedar in Alaska to date. Thus, this is an exciting opportunity to use this new chronology for potentially innovative projects.

Preliminary investigation of the ring width series

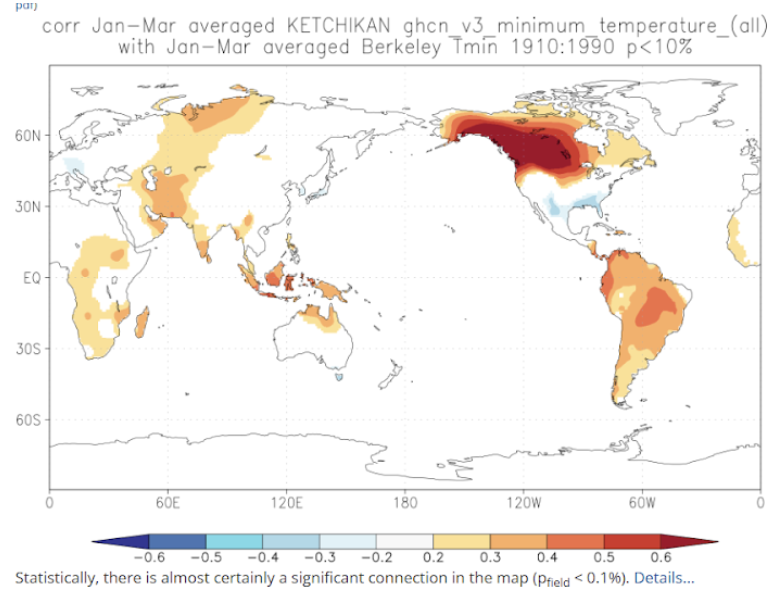

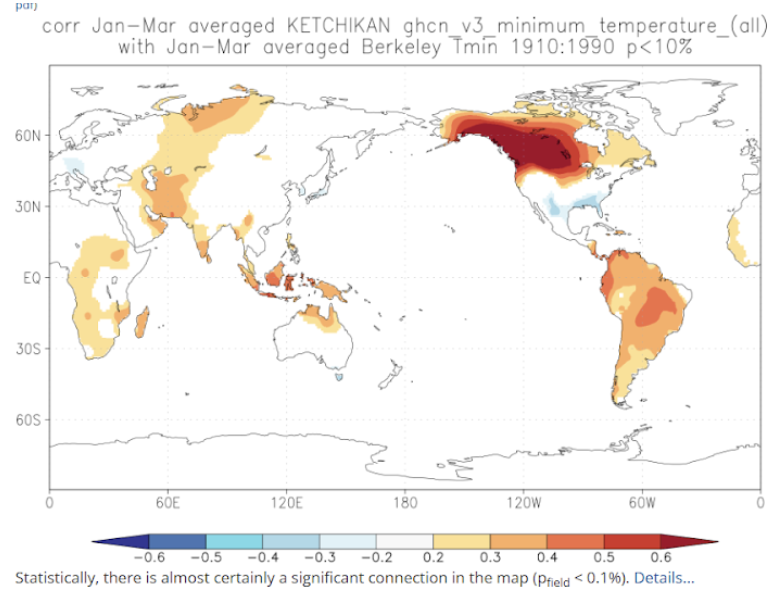

Once samples have been properly collected and prepared for analysis, a preliminary investigation of how the data might be useful can be performed. Before identifying the scope of a study, one needs to know what phenomenon in particular the tree ring chronology is being used to study. This is easily accomplished by loading a tree ring chronology and comparing it with an existing observational dataset. Often, in dendrochronology, this will be a climatic data set (average, minimum and maximum temperatures, precipitation, etc.) because trees are the most sensitive to climatic variables. However, finding which climatic variable a particular chronology is sensitive to can be trickier.

A correlation field demonstrating the high correlation between our Western red cedar chronology and winter minimum temperature in Alaska. Note the high positive correlations of the tree-ring site and much of Alaska and Western Canada.

To accomplish this, our research team loaded our master Alaskan red cedar chronology into an online climate analysis tool called KNMI Climate Explorer (Trouet & Van Oldenborgh, 2013), a useful website that contains a plethora of observational and modeled climatic datasets. This website also allows the user to correlate datasets, which is how our team, through trial and error, found a climatic variable that our chronology is sensitive to. For this particular red cedar chronology, we found that the chronology is sensitive to winter minimum temperatures. This means that our chronology dataset has a high positive correlation with the observational dataset for this particular variable. The team is working on understanding why winter minimum temperatures are most strongly correlated with the site.

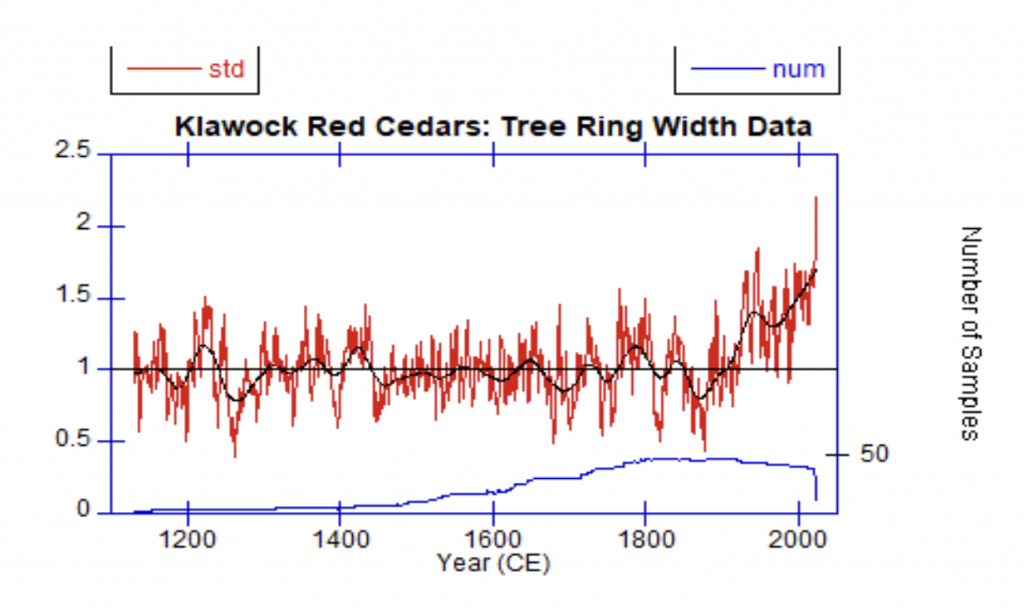

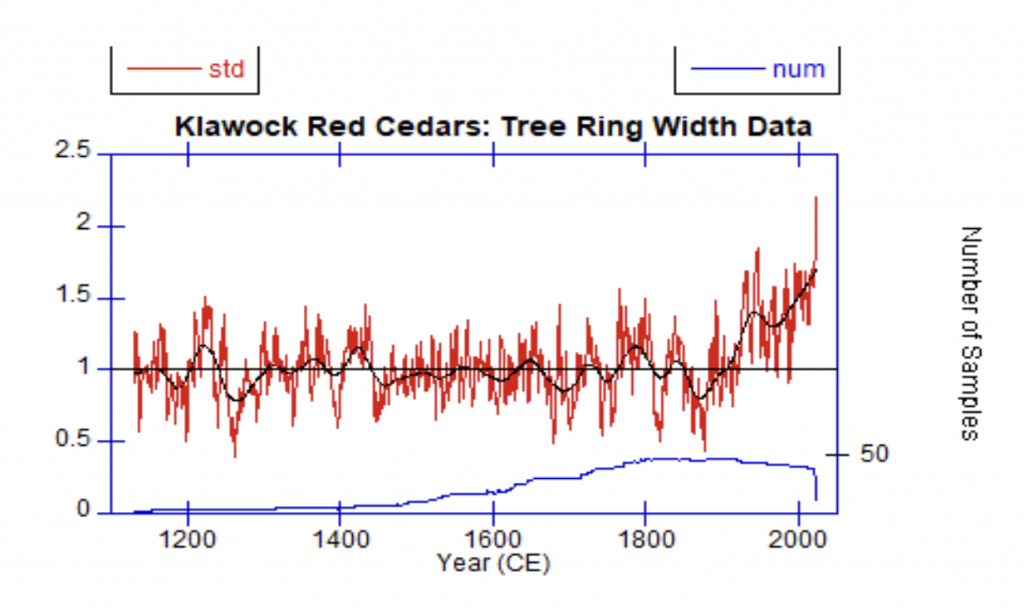

Red cedar chronology (red) the blue line is the sample size. The 1876 ring is the most narrow of the record. Note the increase in tree growth over the past century.

Next steps

Now that we have identified a climatic variable to which our chronology is sensitive, our team can begin more detailed analysis of the chronology. Each of the SEAK25 Team will pick a more narrow topic on which to complete an in-depth research project throughout the course of the summer and the following school year. Potential projects might include an evaluation of the evolution of the Aleutian low-pressure system, an investigation of the Indian Ocean teleconnection recognized in western red cedar, a reconstruction of Great Lakes water levels, and possible snowpack reconstructions in the Sierra Nevada.

References cited

Holmes, R. L. (1983). Computer-assisted quality control in tree-ring dating and measurement, Tree Ring Research, v.43, 69-78.

Maxwell, R. S., & Larsson, L. A. (2021). Measuring tree-ring widths using the CooRecorder software application. Dendrochronologia, 67, 125841.

Trouet, V., & Van Oldenborgh, G. J. (2013). KNMI Climate Explorer: a web-based research tool for high-resolution paleoclimatology. Tree-Ring Research, 69(1), 3-13.

Alexandria, Virginia.– Today Wooster Geologists Greg Wiles and Nick Wiesenberg visited Gloria and me in our new home in northern Virginia. It was great to see treasured old friends from the department. After lunch we visited a tree in our neighborhood claimed to date back to the days of George Washington.

Alexandria, Virginia.– Today Wooster Geologists Greg Wiles and Nick Wiesenberg visited Gloria and me in our new home in northern Virginia. It was great to see treasured old friends from the department. After lunch we visited a tree in our neighborhood claimed to date back to the days of George Washington. This chestnut oak (Quercus montana) overnight dropped a large load of its distinctive elongated acorns, which you can see on the ground around the sign.

This chestnut oak (Quercus montana) overnight dropped a large load of its distinctive elongated acorns, which you can see on the ground around the sign.