The beautiful fossil shrimp above is Aeger tipularis (Schlotheim, 1822), and it comes from one of the most famous rock units: the Solnhofen Plattenkalk (Tithonian, Upper Jurassic) of Germany. (The Solnhofen is well known for its extraordinary fossils, including the fossil bird Archaeopteryx.) This shrimp is yet another generous gift to the Department of Geology from George Chambers (’79).

The beautiful fossil shrimp above is Aeger tipularis (Schlotheim, 1822), and it comes from one of the most famous rock units: the Solnhofen Plattenkalk (Tithonian, Upper Jurassic) of Germany. (The Solnhofen is well known for its extraordinary fossils, including the fossil bird Archaeopteryx.) This shrimp is yet another generous gift to the Department of Geology from George Chambers (’79).

The shrimp in the Solnhofen are very well preserved. Note the long, long antennae and the tiny spines on the carapace. (I suspect, though, that parts of this specimen have been enhanced with ink by a commercial collector, especially the legs.)

Aeger tipularis was described in 1822 by Ernst Friedrich, Baron von Schlotheim (1764-1832), a prolific German paleontologist we profiled earlier. The drawing above is the original reconstruction by Schlotheim (1822, pl. 2, fig. 1; Solnhofen Lithographic Limestone, Solnhofen area; Lower Tithonian, Hybonotum Zone; width of figure 23.7 cm.)

References:

Garassino, A. and Teruzzi, G. 1990. The genus Aeger MÜNSTER, 1839 in the Sinemurian of Osteno in Lombardy (Crustacea, Decapoda). Atti della Società Italiana di Scienze Naturali e del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano 131: 105-136.

Schlotheim, E.F. von. 1822. Nachträge zur Petrefactenkunde (Addenda al Petrefactenkunde). Gotha, Beckersche Buchhandlung.

Schweigert, G. 2001. The late Jurassic decapod species Aeger tipularius (Schlotheim, 1822) (Crustacea: Decapoda: Aegeridae). Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Series B, 309: 1-10.

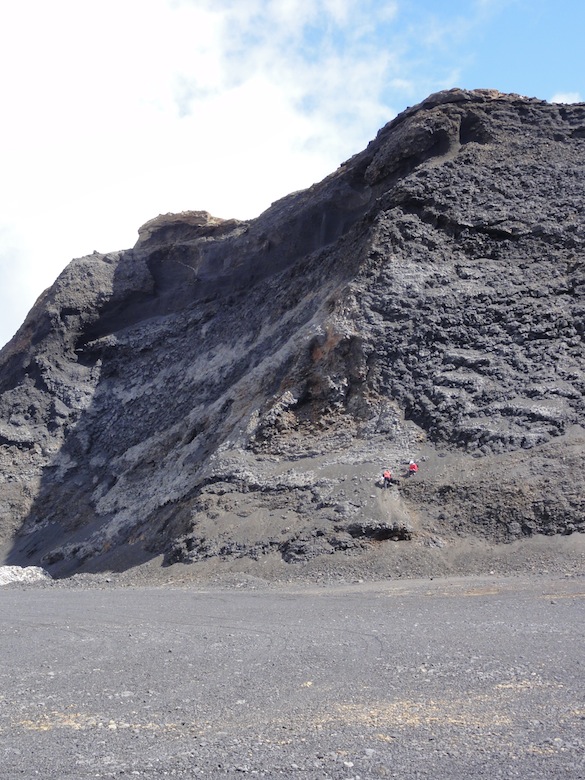

CATANIA, SICILY, ITALY–This summer Wooster’s Team Italy consists of only me. Maybe in the future I’ll take students here for Independent Study projects depending on what I find. I’ve just arrived in the city of Catania on the eastern coast of Sicily. Above is a view of the gorgeous Mount Etna from the plane as we landed. This volcano dominates the city, both structurally and historically. More on that later. Twenty-three hours of travel through four airports has tuckered me out. Luckily we have an early dinner at 8:00 p.m.

CATANIA, SICILY, ITALY–This summer Wooster’s Team Italy consists of only me. Maybe in the future I’ll take students here for Independent Study projects depending on what I find. I’ve just arrived in the city of Catania on the eastern coast of Sicily. Above is a view of the gorgeous Mount Etna from the plane as we landed. This volcano dominates the city, both structurally and historically. More on that later. Twenty-three hours of travel through four airports has tuckered me out. Luckily we have an early dinner at 8:00 p.m.