Time for a trace fossil! This is one of my favorite ichnogenera (the trace fossil equivalent of a biological genus). It is Gyrochorte Heer, 1865, from the Middle Jurassic (Bajocian) Carmel Formation of southwestern Utah (near Gunlock; locality C/W-142). It was collected on an Independent Study field trip a long, long time ago with Steve Smail. We are looking at a convex epirelief, meaning the trace is convex to our view (positive) on the top bedding plane. This is how Gyrochorte is usually recognized.

Time for a trace fossil! This is one of my favorite ichnogenera (the trace fossil equivalent of a biological genus). It is Gyrochorte Heer, 1865, from the Middle Jurassic (Bajocian) Carmel Formation of southwestern Utah (near Gunlock; locality C/W-142). It was collected on an Independent Study field trip a long, long time ago with Steve Smail. We are looking at a convex epirelief, meaning the trace is convex to our view (positive) on the top bedding plane. This is how Gyrochorte is usually recognized.

A quick confirmation that we are looking at Gyrochorte is provided by turning the specimen over and looking at the bottom of the bed, the hyporelief. We see above a simple double track in concave (negative) hyporelief. Gyrochorte typically penetrates deep in the sediment, generating a trace that penetrates through several layers.

A quick confirmation that we are looking at Gyrochorte is provided by turning the specimen over and looking at the bottom of the bed, the hyporelief. We see above a simple double track in concave (negative) hyporelief. Gyrochorte typically penetrates deep in the sediment, generating a trace that penetrates through several layers.

Gyrochorte is bilobed (two rows of impressions). When the burrowing animal took a hard turn, as above, the impressions separate and show feathery distal ends.

Gyrochorte is bilobed (two rows of impressions). When the burrowing animal took a hard turn, as above, the impressions separate and show feathery distal ends.

Gyrochorte traces can become complex intertwined, and their detailed features can change along the same trace.

Gyrochorte traces can become complex intertwined, and their detailed features can change along the same trace.

This is a model of Gyrochorte presented by Gibert and Benner (2002, fig. 1). A is a three-dimensional view of the trace, with the top of the bed at the top; B is the morphology of an individual layer; C is the typical preservation of Gyrochorte.

This is a model of Gyrochorte presented by Gibert and Benner (2002, fig. 1). A is a three-dimensional view of the trace, with the top of the bed at the top; B is the morphology of an individual layer; C is the typical preservation of Gyrochorte.

Our Gyrochorte is common in the oobiosparites and grainstones of the Carmel Formation (mostly in Member D). The paleoenvironment here appears to have been shallow ramp shoal and lagoonal. Other trace fossils in these units include Nereites, Asteriacites, Chondrites, Palaeophycus, Monocraterion and Teichichnus. (I also ran into Gyrochorte in the beautiful Triassic of southern Israel.)

So what kind of animal produced Gyrochorte? There is no simple answer. The animal burrowed obliquely in a series of small steps. Most researchers attribute this to a deposit-feeder searching through sediments rather poor in organic material. It may have been some kind of annelid worm (always the easiest answer!) or an amphipod-like arthropod. There is no trace like it being produced today.

We have renewed interest in Gyrochorte because a team of Wooster Geologists is going to southern Utah this summer to work in these wonderful Jurassic sections.

Oswald Heer (1809-1883) named Gyrochorte in 1865. He was a Swiss naturalist with very diverse interests, from insects to plants to the developing science of trace fossils. Heer was a very productive professor of botany at the University of Zürich. In paleobotany alone he described over 1600 new species. One of his contributions was the observation that the Arctic was not always as cold as it is now and was likely an evolutionary center for the radiation of many European organisms.

Oswald Heer (1809-1883) named Gyrochorte in 1865. He was a Swiss naturalist with very diverse interests, from insects to plants to the developing science of trace fossils. Heer was a very productive professor of botany at the University of Zürich. In paleobotany alone he described over 1600 new species. One of his contributions was the observation that the Arctic was not always as cold as it is now and was likely an evolutionary center for the radiation of many European organisms.

References:

Gibert, J.M. de and Benner, J.S. 2002. The trace fossil Gyrochorte: ethology and paleoecology. Revista Espanola de paleontologia 17: 1-12.

Heer, O. 1864-1865. Die Urwelt der Schweiz. 1st edition, Zurich. 622 pp.

Heinberg, C. 1973. The internal structure of the trace fossils Gyrochorte and Curvolithus. Lethaia 6: 227-238.

Karaszewski, W. 1974. Rhizocorallium, Gyrochorte and other trace fossils from the Middle Jurassic of the Inowlódz Region, Middle Poland. Bulletin of the Polish Academy of Sciences 21: 199-204.

Sprinkel, D.A., Doelling, H.H., Kowallis, B.J., Waanders, G., and Kuehne, P.A., 2011, Early results of a study of Middle Jurassic strata in the Sevier fold and thrust belt, Utah, in Sprinkel, D.A., Yonkee, W.A., and Chidsey, T.C., Jr. eds., Sevier thrust belt: Northern and central Utah and adjacent areas, Utah Geological Association 40: 151–172.

Tang, C.M., and Bottjer, D.J., 1996, Long-term faunal stasis without evolutionary coordination: Jurassic benthic marine paleocommunities, Western Interior, United States: Geology 24: 815–818.

Wilson. M.A. 1997. Trace fossils, hardgrounds and ostreoliths in the Carmel Formation (Middle Jurassic) of southwestern Utah. In: Link, P.K. and Kowallis, B.J. (eds.), Mesozoic to Recent Geology of Utah. Brigham Young University Geology Studies 42, part II, p. 6-9.

[An earlier version of this article was posted on April 17, 2015.]

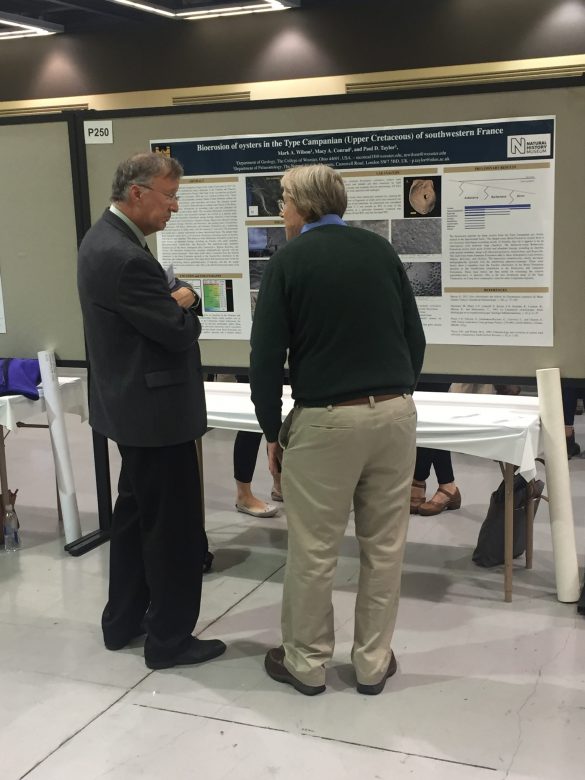

Above is another beautiful image from Paul Taylor’s paleontological lab at the Natural History Museum, London. It is one of our fossil oysters (Pycnodonte vesicularis) from the French Type Campanian collected in the town of Archiac in southwestern France on our most enjoyable expedition this past summer. The fine crossing short grooves are bite marks produced by grazing regular echinoids (sea urchins). They form the trace fossil Gnathichnus pentax Bromley, 1975. You can learn more about this type of fossil in a previous blog entry describing Cretaceous Gnathichnus from southern Israel.

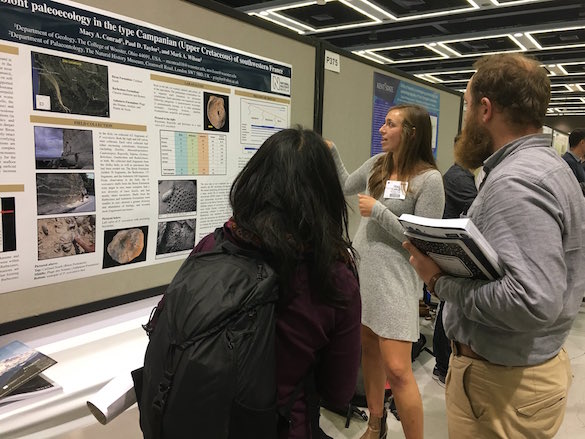

Above is another beautiful image from Paul Taylor’s paleontological lab at the Natural History Museum, London. It is one of our fossil oysters (Pycnodonte vesicularis) from the French Type Campanian collected in the town of Archiac in southwestern France on our most enjoyable expedition this past summer. The fine crossing short grooves are bite marks produced by grazing regular echinoids (sea urchins). They form the trace fossil Gnathichnus pentax Bromley, 1975. You can learn more about this type of fossil in a previous blog entry describing Cretaceous Gnathichnus from southern Israel. This is a good time to update our readers on the French Campanian sclerobiont project. Macy Conrad (’17) has done extraordinary work identifying the hundreds of encrusting bryozoans on our oysters. She is using a series of mugshots of Campanian bryozoans produced by our colleague Paul Taylor to name our specimens as accurately as possible. All the pink you see in these trays represents bryozoans that have been identified.

This is a good time to update our readers on the French Campanian sclerobiont project. Macy Conrad (’17) has done extraordinary work identifying the hundreds of encrusting bryozoans on our oysters. She is using a series of mugshots of Campanian bryozoans produced by our colleague Paul Taylor to name our specimens as accurately as possible. All the pink you see in these trays represents bryozoans that have been identified. Here is a closer view. Very distinct patterns of diversification of bryozoans and trace fossils upward through the stratigraphic column are emerging. Macy will continue this work next semester as she finishes her Independent Study thesis. I will be doing my parts as well, but from a bit of a distance: I’ll be on a research leave next semester.

Here is a closer view. Very distinct patterns of diversification of bryozoans and trace fossils upward through the stratigraphic column are emerging. Macy will continue this work next semester as she finishes her Independent Study thesis. I will be doing my parts as well, but from a bit of a distance: I’ll be on a research leave next semester.