Stromatoporoids are very common fossils in the Silurian and Devonian of Ohio and Indiana, especially in carbonate rocks like the Columbus Limestone (from which the above specimen was collected). Wooster geologists encountered them frequently on our Estonia expeditions in the last few years, and we worked with at least their functional equivalents in the Jurassic of Israel (Wilson et al., 2008).

Stromatoporoids are very common fossils in the Silurian and Devonian of Ohio and Indiana, especially in carbonate rocks like the Columbus Limestone (from which the above specimen was collected). Wooster geologists encountered them frequently on our Estonia expeditions in the last few years, and we worked with at least their functional equivalents in the Jurassic of Israel (Wilson et al., 2008).

For their abundance, though, stromatoporoids still are a bit mysterious. We know for sure that they were marine animals of some kind, and they formed reefs in clear, warm seas rich in calcium carbonate (DaSilva et al., 2011). Because of this tropical habit, early workers believed they were some kind of coral, but now most paleontologists believe they were sponges. Stromatoporoids appear in the Ordovician and are abundant into the Early Carboniferous. The group seems to disappear until the Mesozoic, when they again become common with the same form and life habits lasting until extinction in the Late Cretaceous (Stearn et al., 1999).

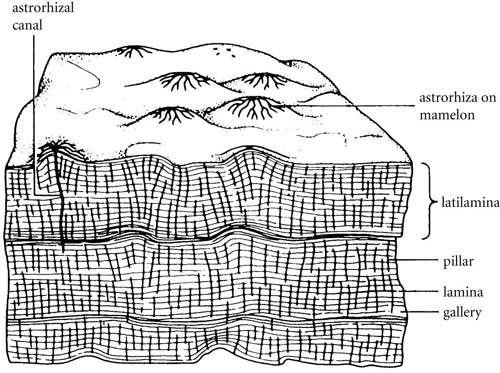

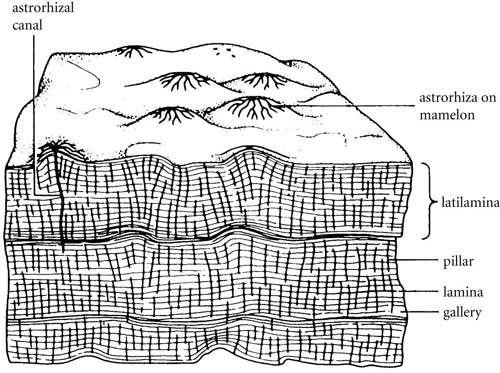

The typical stromatoporoid has a thick skeleton of calcite with horizontal laminae, vertical pillars, mounds on the upper surface called mamelons, and dendritic canals called astrorhizae shallowly inscribed on the mamelons. These astrorhizae are the key to deciphering what the stromatoproids. They are very similar to those on modern hard sponges called sclerosponges. Stromatoporoids appear to be a kind of sclerosponge with a few significant differences (like a calcitic instead of an aragonitic skeleton).

Stromatoporoid anatomy from Boardman et al. (1987).

Top surface of a stromatoporoid from the Columbus Limestone showing the mamelons.

There is considerable debate about whether the Paleozoic stromatoporoids are really ancestral to the Mesozoic versions. There may instead be some kind of evolutionary convergence between two groups of hard sponges. The arguments are usually at the microscopic level!

The stromatoporoids were originally named by Nicholson and Murie in 1878. This gives us a chance to introduce another 19th Century paleontologist whose name we often see on common fossil taxa: Henry Alleyne Nicholson (1844-1899). Nicholson was a biologist and geologist born in England and educated in Germany and Scotland. He was an accomplished writer, authoring several popular textbooks, and a spectacular artist of the natural world. Nicholson taught in many universities in Canada and Great Britain, finally ending his career as Regius Professor of Natural History at the University of Aberdeen.

Henry Alleyne Nicholson (1844-1899) from the University of Aberdeen museum website.

Henry Alleyne Nicholson (1844-1899) from the University of Aberdeen museum website.

References:

Boardman, R.S., Cheetham, A.H. and Rowell, A.J. 1987. Fossil Invertebrates. Wiley Publishers. 728 pages.

DaSilva, A., Kershaw, S. and Boulvain, F. 2011. Stromatoporoid palaeoecology in the Frasnian (Upper Devonian) Belgian platform, and its applications in interpretation of carbonate platform environments. Palaeontology 54: 883–905.

Nicholson, H.A. and Murie, J. 1878. On the minute structure of Stromatopora and its allies. Linnean Society, Journal of Zoology 14: 187-246.

Stearn, C.W., Webby, B.D., Nestor, H. and Stock, C.W. 1999. Revised classification and terminology of Palaeozoic stromatoporoids. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 44: 1-70.

Wilson, M.A., Feldman, H.R., Bowen, J.C. and Avni, Y. 2008. A new equatorial, very shallow marine sclerozoan fauna from the Middle Jurassic (late Callovian) of southern Israel. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 263: 24-29.

[Originally published on October 30, 2011]

The sharp little conical fossils above are common Paleozoic fossils, especially in the Devonian. They are tentaculitids now most commonly placed in the Class Tentaculitoidea Ljashenko 1957. Tentaculitids appeared in the Ordovician and disappeared sometime around the end of the Carboniferous and beginning of the Permian. These specimens are from the Devonian of Maryland.

The sharp little conical fossils above are common Paleozoic fossils, especially in the Devonian. They are tentaculitids now most commonly placed in the Class Tentaculitoidea Ljashenko 1957. Tentaculitids appeared in the Ordovician and disappeared sometime around the end of the Carboniferous and beginning of the Permian. These specimens are from the Devonian of Maryland.