I am thrilled to announce the publication today of this comprehensive open-access paper in Science Advances: “Quantifying ecospace utilization and ecosystem engineering during the early Phanerozoic — The role of bioturbation and bioerosion“. It was a long time coming after a massive data collection and analysis project led by the indefatigable and highly productive team of Luis Buatois and Gabriela Mángano (University of Saskatchewan). We even have a news release. (Above image: Trace fossils in the Early Cambrian Gog Group, Lake Louise, Alberta, Canada. See earlier blog post for details.)

I am thrilled to announce the publication today of this comprehensive open-access paper in Science Advances: “Quantifying ecospace utilization and ecosystem engineering during the early Phanerozoic — The role of bioturbation and bioerosion“. It was a long time coming after a massive data collection and analysis project led by the indefatigable and highly productive team of Luis Buatois and Gabriela Mángano (University of Saskatchewan). We even have a news release. (Above image: Trace fossils in the Early Cambrian Gog Group, Lake Louise, Alberta, Canada. See earlier blog post for details.)

The abstract —

The Cambrian explosion (CE) and the great Ordovician biodiversification event (GOBE) are the two most important radiations in Paleozoic oceans. We quantify the role of bioturbation and bioerosion in ecospace utilization and ecosystem engineering using information from 1367 stratigraphic units. An increase in all diversity metrics is demonstrated for the Ediacaran-Cambrian transition, followed by a decrease in most values during the middle to late Cambrian, and by a more modest increase during the Ordovician. A marked increase in ichnodiversity and ichnodisparity of bioturbation is shown during the CE and of bioerosion during the GOBE. Innovations took place first in offshore settings and later expanded into marginal-marine, nearshore, deep-water, and carbonate environments. This study highlights the importance of the CE, despite its Ediacaran roots. Differences in infaunalization in offshore and shelf paleoenvironments favor the hypothesis of early Cambrian wedge-shaped oxygen minimum zones instead of a horizontally stratified ocean.

In short, this is a study of trace fossil occurrences during the Ediacaran, Cambrian and Ordovician periods. Trace fossils are evidence of organism activity, so we are looking at the early evolution of animal behavior in space and time. The paleoenvironmental conclusions include support for Early Cambrian laterally discontinuous, wedge-shaped oxygen minimum zones, which have implications for Cambrian community development.

The illustrations in this paper do not fit well into this blog format. The above is part of Figure 2, a plot of changes in modes of life (ML), ecosystem engineering (EE), maximum alpha ichnodiversity (AI), global ichnodiversity (GI), and ichnodisparity (Id) in all environments. Counts are plotted at the middle of the series intervals.

The illustrations in this paper do not fit well into this blog format. The above is part of Figure 2, a plot of changes in modes of life (ML), ecosystem engineering (EE), maximum alpha ichnodiversity (AI), global ichnodiversity (GI), and ichnodisparity (Id) in all environments. Counts are plotted at the middle of the series intervals.

Another portion of Figure 2 showing some of the ecospace patterns. Since the paper is open-access, you can click here for the originals.

Another portion of Figure 2 showing some of the ecospace patterns. Since the paper is open-access, you can click here for the originals.

Note that the data for this work came from 1367 stratigraphic units. This paper is thus based on generations of geological and paleontological articles. It is affirming to know that hundreds of small, local descriptive studies eventually add up to major evolutionary and paleoenvironmental models. Several of those projects were done by Wooster faculty, students, and alumni. Some of the earlier comprehensive data gathering and analysis can be found in Buatois et al. (2016) and Buatois et al. (2017).

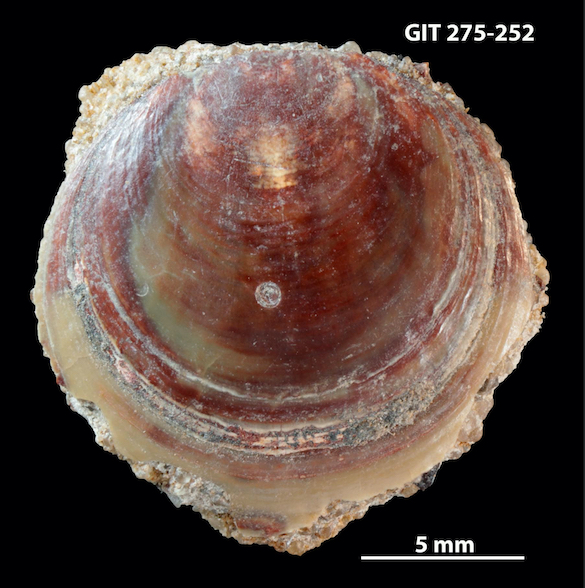

My primary job on this international team of scientists was to join with Max Wisshak (Marine Research Department, Senckenberg am Meer, Wilhelmshaven, Germany) to sort out the bioerosion data and patterns. (Bioerosion is the biological abrasion of hard substrates such as rocks and shells.) Max generally focused on microbioerosion and I mostly did macrobioerosion. We showed that bioerosion had a dramatic increase in diversity during the Ordovician, probably because hard substrates like shells and hardgrounds became more available.

This was an exciting project. I look forward to future applications of the data and methodology we employed in this work. There are many opportunities for Wooster Independent Study students here. Thanks again for the leadership of Luis Buatois and Gabriela Mángano.

References:

Buatois, L.A., Mángano, M.G., Minter, N.J., Zhou, K., Wisshak, M., Wilson, M.A. and Olea, R.A. 2020. Quantifying ecospace utilization and ecosystem engineering during the early Phanerozoic — The role of bioturbation and bioerosion. Science Advances 6: eabb0618.

Buatois, L.A., Mángano, M.G., Olea, R.A. and Wilson, M.A. 2016. Decoupled evolution of soft and hard substrate communities during the Cambrian Explosion and Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A. 113: 6945–6948.

Buatois, L.A., Wisshak, M., Wilson, M.A. and Mángano, M.G. 2017. Categories of architectural designs in trace fossils: A measure of ichnodisparity. Earth Science Reviews 164: 102–181.

Once again I’m proud to be on Olev Vinn’s team with this new article on predatory drill holes in Cambrian and Ordovician brachiopods. Predation in the fossil record is always interesting, especially in the early Paleozoic. Here is the abstract with explanatory links added:

Once again I’m proud to be on Olev Vinn’s team with this new article on predatory drill holes in Cambrian and Ordovician brachiopods. Predation in the fossil record is always interesting, especially in the early Paleozoic. Here is the abstract with explanatory links added:

The many faces of Browns Lake. Thanks to The Nature Conservancy (TNC) for allowing us to do this work and for managing this amazing resource.

The many faces of Browns Lake. Thanks to The Nature Conservancy (TNC) for allowing us to do this work and for managing this amazing resource.

The slump from above. Note the arcuate scarp that marks the upper reaches of the slump block – a series of grabens and scarps stair-step their way into the valley.

The slump from above. Note the arcuate scarp that marks the upper reaches of the slump block – a series of grabens and scarps stair-step their way into the valley.