WOOSTER, OHIO–A dozen Wooster Geologists participated today in the annual Wooster Senior Research Symposium: A Celebration of Independent Study! All did superb presentations that were very well received. The geology portion began in the morning with talks from Team Utah 3.0, led by Dr. Meagen Pollock and Dr. Shelley Judge. Michael Williams (’16) gave his talk entitled “Emplacement Processes and Monogenetic Classification of Ice Springs Volcanic Field, Central Utah”. Here’s a link to Michael’s field work.

WOOSTER, OHIO–A dozen Wooster Geologists participated today in the annual Wooster Senior Research Symposium: A Celebration of Independent Study! All did superb presentations that were very well received. The geology portion began in the morning with talks from Team Utah 3.0, led by Dr. Meagen Pollock and Dr. Shelley Judge. Michael Williams (’16) gave his talk entitled “Emplacement Processes and Monogenetic Classification of Ice Springs Volcanic Field, Central Utah”. Here’s a link to Michael’s field work.

Kelli Baxstrom (’16) also spoke for Team Utah with her talk entitled: “Ice Springs Volcanic Field: New Insights and History for a Series of Complex Eruptions”. Here’s a link to Kelli’s field work.

Kelli Baxstrom (’16) also spoke for Team Utah with her talk entitled: “Ice Springs Volcanic Field: New Insights and History for a Series of Complex Eruptions”. Here’s a link to Kelli’s field work.

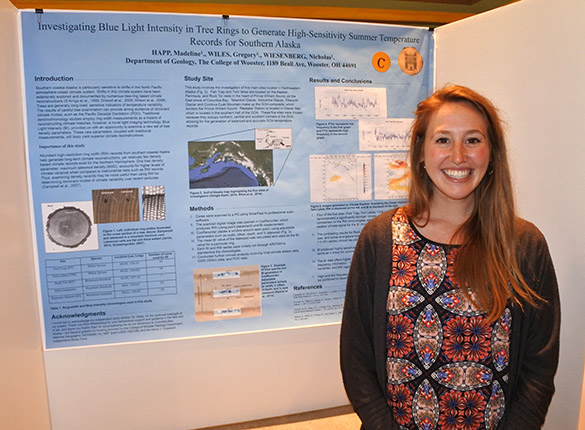

Maddie Happ (’16) had a poster entitled: “Investigating Blue Light Intensity in Tree Rings to Generate High-Sensitivity Summer Temperature Records for Southern Alaska”. Here’s a link to Maddie’s field work.

Maddie Happ (’16) had a poster entitled: “Investigating Blue Light Intensity in Tree Rings to Generate High-Sensitivity Summer Temperature Records for Southern Alaska”. Here’s a link to Maddie’s field work.

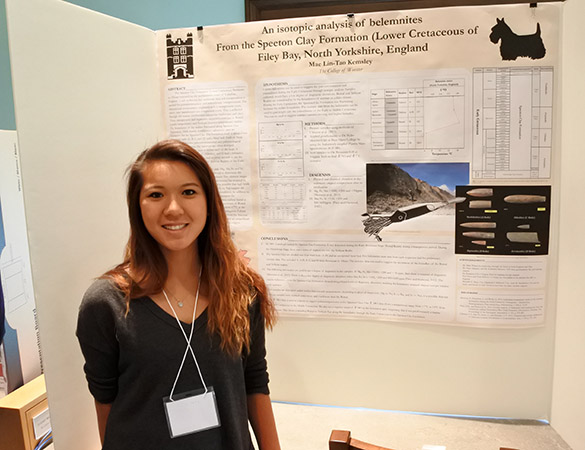

Mae Kemsley (’16) presented: “An isotopic analysis of belemnites from the Speeton Clay Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of Filey Bay, North Yorkshire, England”. Here’s a link to Mae’s field work.

Mae Kemsley (’16) presented: “An isotopic analysis of belemnites from the Speeton Clay Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of Filey Bay, North Yorkshire, England”. Here’s a link to Mae’s field work.

Meredith Mann (’16) gave a poster entitled: “Paleoecology and Depositional Environments of the Passage Beds Member at Filey Brigg (Upper Jurassic, North Yorkshire, England)”. Here’s a link to Meredith’s field work.

Meredith Mann (’16) gave a poster entitled: “Paleoecology and Depositional Environments of the Passage Beds Member at Filey Brigg (Upper Jurassic, North Yorkshire, England)”. Here’s a link to Meredith’s field work.

Dan Misinay (’16) presented: “Late Holocene Glacial History of Muir Inlet, Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska”. Here’s a link to Dan’s field work.

Dan Misinay (’16) presented: “Late Holocene Glacial History of Muir Inlet, Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska”. Here’s a link to Dan’s field work.

Brittany Nicholson (’16) gave a poster entitled: “Mentoring Structures in Undergraduate Research”.

Brittany Nicholson (’16) gave a poster entitled: “Mentoring Structures in Undergraduate Research”.

Eric Parker (’16) presented: “Analysis of Water Quality Parameters and Preliminary Investigation into the Impacts of Human Access on the Water Quality of the Nisqually River, Mount Rainier National Park”.

Eric Parker (’16) presented: “Analysis of Water Quality Parameters and Preliminary Investigation into the Impacts of Human Access on the Water Quality of the Nisqually River, Mount Rainier National Park”.

Krysden Schantz (’16) gave: “The Use of Multiple Dating Methods to Determine the Age of Basalt in the Ice Springs Volcanic Field, Millard County, Utah”. Here’s a link to Krysden’s field work.

Krysden Schantz (’16) gave: “The Use of Multiple Dating Methods to Determine the Age of Basalt in the Ice Springs Volcanic Field, Millard County, Utah”. Here’s a link to Krysden’s field work.

Adam Silverstein (’16) presented: “Regional Volcanic Extinction as a Mechanism for Subsidence in the Vatnsdalur Structural Basin, Skagi Peninsula, Northwest Iceland”. You can find Adam in Iceland in this post.

Adam Silverstein (’16) presented: “Regional Volcanic Extinction as a Mechanism for Subsidence in the Vatnsdalur Structural Basin, Skagi Peninsula, Northwest Iceland”. You can find Adam in Iceland in this post.

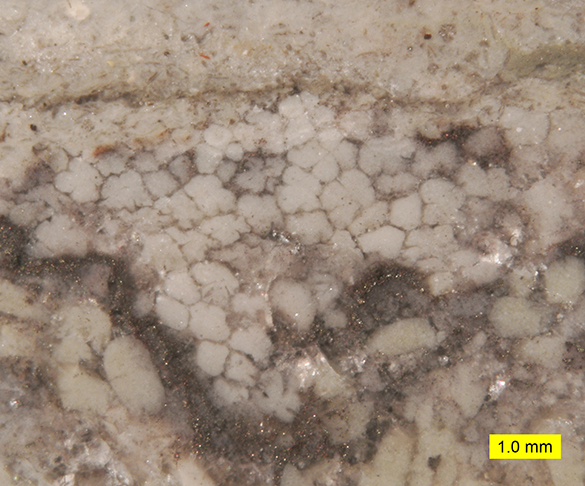

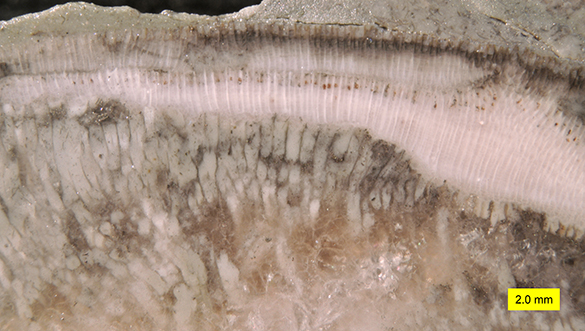

Kaitlin Starr (’16) is a double major in studio art and geology. Maybe we shouldn’t have been surprised to see her double-booked for the same time slot at the symposium. Her geology I.S. thesis poster was titled: “Reconstructing Glacial History from Forests Preserved in the Wake of the Catastrophic Retreating Columbia and Wooster Glaciers, Prince William Sound, Alaska”. Here’s a link to Kaitlin’s field work. She is shown above with her art exhibit: “Exploring the Unknown: A Ceramic Journey Through the Sea of Imagination”. She made fantastical representations of marine creatures that do not exist but look eerily like beautiful fossils.

Kaitlin Starr (’16) is a double major in studio art and geology. Maybe we shouldn’t have been surprised to see her double-booked for the same time slot at the symposium. Her geology I.S. thesis poster was titled: “Reconstructing Glacial History from Forests Preserved in the Wake of the Catastrophic Retreating Columbia and Wooster Glaciers, Prince William Sound, Alaska”. Here’s a link to Kaitlin’s field work. She is shown above with her art exhibit: “Exploring the Unknown: A Ceramic Journey Through the Sea of Imagination”. She made fantastical representations of marine creatures that do not exist but look eerily like beautiful fossils.

I call them Kaitlin’s Kreations, and think they’re wonderful!

I call them Kaitlin’s Kreations, and think they’re wonderful!

Congratulations on your successful Independent Study projects, Wooster Seniors!