TALLINN, ESTONIA–Scientific museums preserve specimens and information from generations of researchers, collectors and students. The interiors of a typical paleontological museum contains windowless rooms filled almost to the ceiling with cabinets, each with dozens of drawers containing carefully labeled and cataloged specimens. Because information grows rapidly in science, the most important information on those labels is not the identity of the fossils but where they were found. The names and even systematic categories often change over the years as we learn new characteristics of particular groups, but the location information will always be critical for the value of the specimen for future researchers.

Today we visited the Institute of Geology at the Tallinn University of Technology. We were hosted by Dr. Helje Pärnaste, a paleontologist who specializes in Ordovician trilobites. She generously spent the day with us going through the collections. Using one of the best electronic cataloging systems we have ever seen, she was able to take us to drawers containing specimens from our study localities. We were able to add to our faunal lists and see better preserved fossils which will help in our future identifications. We concentrated on crinoids, of course, and were able to calibrate what we found which was truly new and see many other examples.

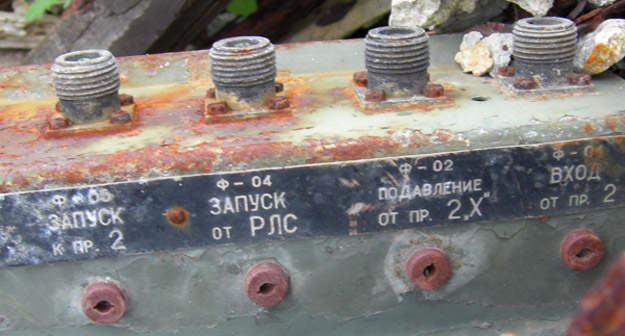

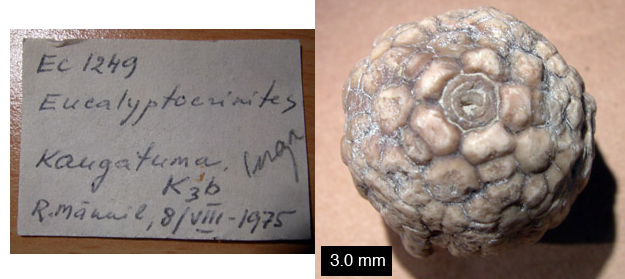

The Estonia Geology Research crew examining specimens in the Institute of Geology collections (left); a typical museum drawer (right).

Much of our work involves finding specimens from our study locations and making quick and simple photographs for later reference.

Again another scientific colleague we did not know before this trip helped us immensely and has become a friend. It is a remarkable universal fellowship. I hope we are able to return many such favors back in the United States.