Editor’s note: Senior Independent Study (I.S.) is a year-long program at The College of Wooster in which each student completes a research project and thesis with a faculty mentor. We particularly enjoy I.S. in the Geology Department because there are so many cool things to do for both the faculty advisor and the student. We are now posting abstracts of each study as they become available. The following was written by Stephanie Jarvis, a senior geology and biology double major from Shelbyville, KY. Here is a link to Stephanie’s final PowerPoint presentation on this project as a movie file (which can be paused at any point). You can see earlier blog posts from her field work by clicking the Alaska tag to the right.

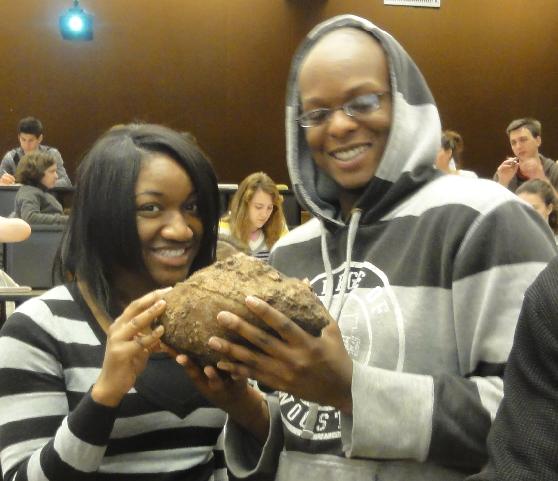

For my IS field work I traveled to Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve, Alaska with my geology advisor, Greg Wiles. Our field crew also consisted of Deb Prinkey (’01), Dan Lawson (CRREL), and Justin Smith, captain of the RV Capelin. My focus was on sampling mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana (Bong.) Carrière) at treeline sites to study climate response and forest health using tree ring analysis. While in Glacier Bay, we also sampled interstadial wood (from forests run over from the glaciers that were now being exposed on the shore) and did some maintenance work on Dan’s climate stations throughout the park. Back in the lab, Wooster junior Sarah Appleton kept me company and helped me out with some of the tree-ring processing, as did Nick Wiesenberg.

An interstadial wood stump, in place. The glacier ran over this tree and buried it in sediment, which is now being washed away.

I ended up processing cores from only one of the three sites I sampled this summer (the others can be fodder for future projects!). In addition, I used data from several other sites sampled in previous years. My data consisted of 3 mountain hemlock sites forming an elevational transect along Beartrack Mountain in Glacier Bay (one described by Alex Trutko ’08), 3 mountain hemlock sites at varying elevations from the mountains around Juneau, AK, and 2 Alaskan yellow-cedar sites (Chamaecyparis nootkatensis (D. Don) Spach) from Glacier Bay used by Colin Mennett (’10). My purpose was to look into the assumption of stationarity in growth response to climate of trees over time and changing climatic conditions. According to the Alaska Climate Research Center, this part of AK as warmed 1.8°C over the past 50 years.

Tree-ring base climate reconstructions are important in our understanding of climatic variations and are a main temperature proxy in IPCC’s 2007 report on climate change. Climate reconstruction is based on the premise that trees at a site are responding to the same environmental variables today that they always have (thus, they are stationary in their response), allowing for the reconstruction of climatic variables using today’s relationship between annual growth and climate.

Temperature reconstructions using different proxies, including tree-rings, from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2007 report.

Recent observations, such as divergence (the uncoupling of long-term trends in temperature and annual growth) and worldwide warming-induced tree mortality, suggest that this assumption of stationarity may not be valid in some cases. Using mean monthly temperature and precipitation data from Sitka, AK that begin in the 1830s, I compared correlations of annual growth in mountain hemlock to climate at different elevations over time. My results indicate that mountain hemlocks at low elevations are experiencing a negative change in response to warm temperatures with time, whereas those at high elevations are experiencing a release in growth with warming. Low-elevation correlation patterns are similar to those of lower-elevation Alaskan yellow-cedar, which is currently in decline due to early loss of protective snowpack with warming. An increasing positive trend in correlation to April precipitation and mountain hemlock growth indicates that spring snowpack may be playing an increased role in mountain hemlock growth as temperatures warm. The high elevation mountain hemlock trends suggest the possibility of tree-line advance, though I was not able to determine if regeneration past the current treeline is occurring. Tree at mid-elevation sites seem to be the least affected by non-stationarity, remaining relatively constant in their growth response throughout the studied time period. This indicates that reconstructions using mid-elevation sites are likely to be more accurate, as the climatic variable they are sensitive to is not as likely to have changed over time.

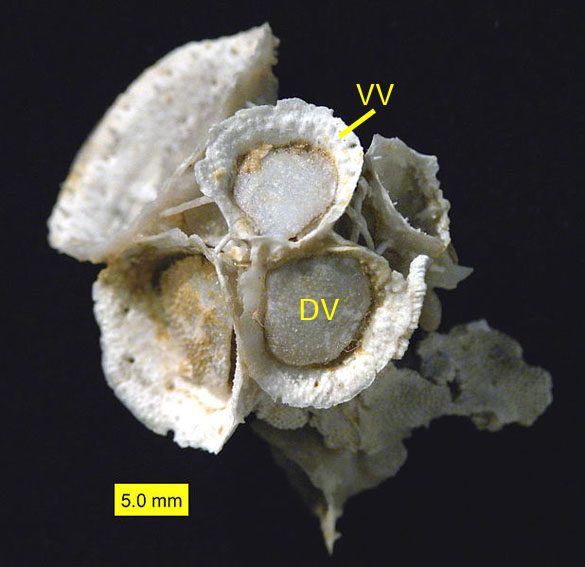

Cedar chronologies (green lines) compared to temperature (brown line). Bar graph represents correlation coefficients between annual ring width and temperature, with colors corresponding to labels on the chronologies (orange is lowest elevation PI, blue is higher elevation ER). Asterisks represent significant correlations. Note that the relationship has changed from being positive at ER during the Little Ice Age to negative by the second half of the 20th century.

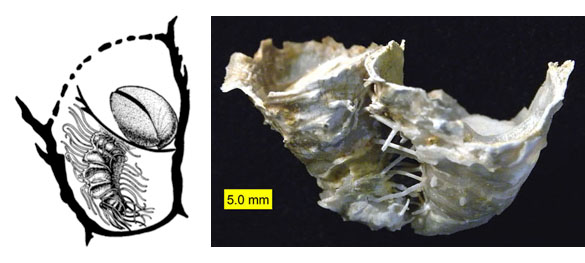

Mountain hemlock chronologies (green lines) compared to temperature (brown line). The top graph is of the Glacier Bay sites, the bottom is of the Juneau sites. Red represents the low elevation sites, green the mid-elevation, and purple the high elevation. Note that the low elevation sites are decreasing in correlation as the cedars have, while the high elevation sites have experienced a release in growth with warming.