Guest Blogger: Sarah Appleton

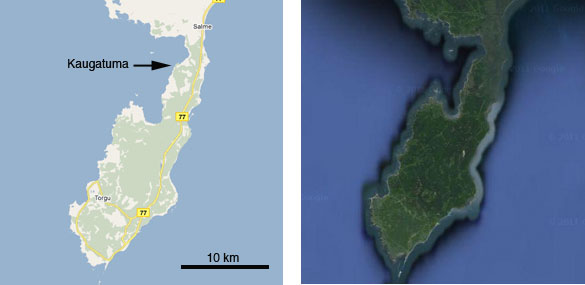

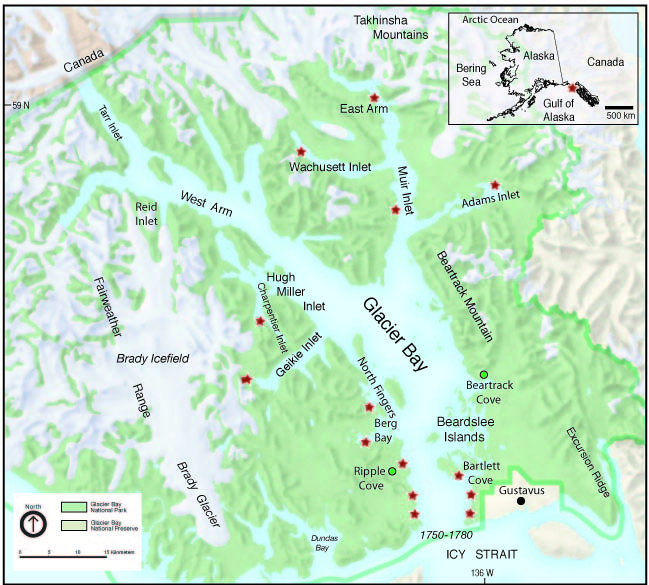

Wooster Geology takes its students all across the globe and this time they have traveled to the distant land of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve (http://www.nps.gov/glba/index.htm), Alaska, for a better look at the sedimentation, ancient forests, and glacial processes at work there. Three of Wooster’s finest, Dr. Greg Wiles, Joe Wilch (Junior), and Sarah Appleton (Senior) ventured out into the Alaska back-country for a chance to study at three amazing sites within Glacier Bay; Wachusett Inlet, Casement Glacier, and Mount Wright. Each site gleaned a tidbit that falls into the overall complex story of glaciations and ice melt throughout the Holocene time period.

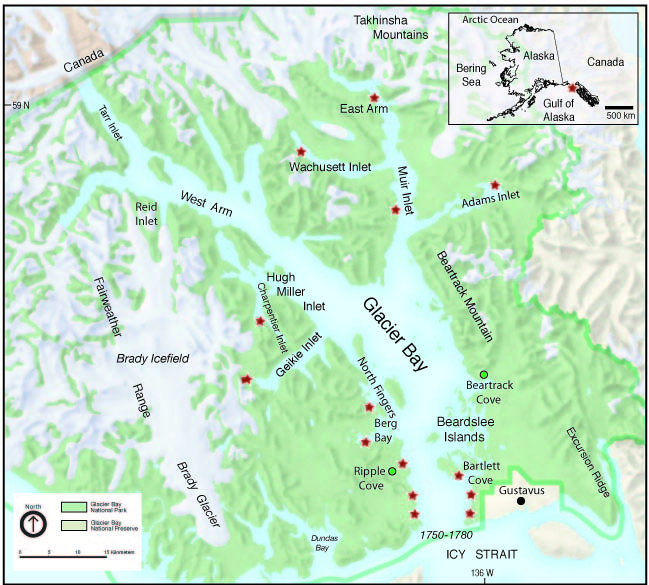

A map of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska.

The team of Wooster geologists set out on the 14th of June for their wilderness study aboard the proud vessel, The Capeland. Captain Justin Smith and the Capeland took out five brave scientists ready to brave the wilderness in order to learn more about the natural world around them.

Captain Smith standing on the front of the Capeland as they are getting ready to leave.

Captain Smith standing on the front of the Capeland as they are getting ready to leave.

- Our team of Wooster Geologists we accompanied out into the field by two noble scientists from the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, Meagan and Ed. They were out studying the effect of wood in the stream on the amount nitrogen present and the presence of different microbial organisms in the water and soil of the stream. They brought with them their brilliant sea faring skiff, Porcupine, (which they affectionately refer to as Porkey) who blazes through land and sea.

Porkey the skiff, blazing a trail on land and sea.

The Capeland dropped both groups of dedicated scientists off at their first campsite, a large outwash fan near the head of Wachusett Inlet. We dropped off our gear and got right to work. The first order of business was to investigate the Plateau Glacier, an ice remnant across the fjord near to Megan and Ed’s site of study. They lead us bravely through the maze of alders to their study site below two small lakes, and pointed us upstream toward the source of the water, the glacier. We hiked up and made our way out of the alder and brush and onto the glacial outwash plane. A cool breeze blew around the glacier, which at first glance appeared to be gone. On a closer inspection we discovered that the glacier was still there, buried in sand and gravel.

Platueau Glacier, an ice remnant, buried in sand and gravel with the melt water from the ice flowing out in front.

We approached the glacier enthusiastically ready to investigate and set about exploring the ice. There were caves in the ice where the glacier had melted and many little braided streams carrying the silty water away from it. All too soon it was time to travel back to meet our fellow scientists and travel back across the fjord. We beat our way back down through the brush and alder to the shore where we met Megan and Ed, who sailed Porkey back across the water to our camp. Once ashore we set up camp and made dinner. It was a great first day in the field.

Sarah Appleton and Joe Wilch exploring Plateau Glacier ice remnant.

Wachusett Inlet: The Unnamed Valley

Day two began bright and early, with oatmeal and hot chocolate or coffee. It was time for the real work began. The plan of attack was to tackle the right side of the recently deglaciated unnamed valley whose base we were camping on. The hike began through a few alders and quickly emerged onto a more tundra like moraine that consisted of large boulders covered in lichen, moss, and dryas. Carefully, we picked out way up the ridge keeping close to the thundering outwash/melt water stream. We walked along the edge inspecting the valley below. What we saw was very promising, large freshly eroded walls of sediment features that helped to tell the story of the past glaciations and deglaciations. We pause frequently to photograph the left wall which we could see as well as to take photos of our beautiful surroundings. As we could, we climbed down into the valley and began to work along the wall mapping out the different sediment layers and taking photographs. We hiked well up into the mountain until we reached a point where the stream divided into two where we took a break for a snack, rest, and more photographs.

Sarah Appleton and Joe Wilch taking a break high on the mountain overlooking Wachusett Inlet.

We made our way back down the valley this time working the other side of the large moraine that was present. The hypothesis we formed was that this moraine was part of the small unnamed glacier at the top of the mountain. Using the same method as before, our team worked back down the mountain looking at the sediment featured in relation to the in situ forests we saw. Once back at camp we made dinner and plans for our next day’s work. Megan and Ed were kind enough to offer us a ride around the large outwash stream the next morning on their way across the fjord so that we would be able to work the other side of the valley. The outwash stream was a bit too large to be crosses on foot except for at low tide. Our return would be at low tide so we planned to attempt to cross the stream on the way back to allow us more freedom while working on the left side of the valley.

Sarah Appleton and Joe Wilch climbing/sliding down the slope for a better look at some in situ tree stumps.

The hike up this side of the valley covered the same type of terrain that we saw on the other side of the valley. Our group crashed through the alder and brush up the opposite side of the moraine to the tundra like section and again kept to the edge of the stream to get a good view of the valley walls. We hiked to the site use below the moraine as we planned the previous day and began to work our way down the valley mapping the different sediment features in relation to the in situ tree stumps. The biggest mystery was what layer of sediment the trees we rooted into. As we worked we pondered this and then we spotted it, a stump that was rooted upright in a layer of dark organic soil. This was the key to being able to figure out more about the first site we were looking at. It was an awesome breakthrough.

Joe Wilch standing above the tree rooted in the organic layer of sediment.

We climbed out of the highest bowl and began to hike down to the second and third bowls repeating our procedure for the first one. Overall it was a productive day! Once we had all the data we thought we could glean from the site for the day we hiked back down the mountain to camp. We were almost to camp the only thing keeping us from it was the raging outwash stream. Dr. Wiles lead the way across the stream carefully picking out a good way. Joe followed once Dr. Wiles had made it across. Finally, Sarah attempted to cross the stream…SPLASH! Down she went for her first swim of the trip. Fortunately, camp was very close so dry clothes were not far away though on the warm Alaskan day the swim was quiet refreshing. This wrapped up our work in Wachusett Inlet.

Joe Wilch crossing the raging water of the outwash stream.

On June 17th the team rose to a bright sunny if a bit cool day. After breakfast Megan and Ed took Porkey up the Inlet to attempt to make radio contact with the outside world so that we would know when the Capeland was arriving to pick us up for our move to Forest Creek and Casement Glacier. As they drove out of sight we began to pack up gear and lay wet gear out to dry in the sun on large boulders. We helped them load their boat and waved them off. After they had left we moved all of our gear down the beach to the shore and settled in for lunch, naps, and time to update our notebooks. We waited patiently for the Capeland, stirring once to move our gear up above high tide as the water came in before the boat arrived. The Capeland dropped us off at Forest Creek, a former outwash stream of Casement Glacier and we set up camp in two beach meadows.

Dr. Wiles setting up camp in the second beach meadow filled with strawberry flowers.

Casement Glacier

Once camp was established and we had helped Megan and Ed unload their gear we decided to make a run up the short trail to Casement Glacier to investigate what we would spend the next three days studying in depth. It was a little bit later in the day about six o’clock in the evening and the outwash was only 3 km away from camp. We began our hike chatting about what we might find once we arrived at the glacier. Beating through a row of alder and what luck! We found a moose trail! The moose trail appeared to go to the glacier, so we began to follow the way of the moose. The moose trail was fairly easy to follow until we arrived to the near end of our journey, where our moose trail swung to the right and away from our goal. We were about two and a half hours into our hike, so much for a short trail! The three of us crashed through a thick bunch of alder and emerged on the endless outwash plain of Casement Glacier.

The outwash plain goes on and on my friends, some people started crossing it not knowing what it was, and it is the outwash plain that never ends!

In the distance we could see a corner of bedrock and Sarah decided that we should walk out to peek around it. That turned out to be a bad decision. The outwash plain and the large section of bedrock tricked the eye and were much farther than they appeared. The three geologists peeked around the corner, caught their breaths, and turned around to head back to camp and dinner.

Casement Glacier

One small glitch occurred, however, once you are in the alder it all tends to look exactly the same and so our brave scientists got turned around looking for the way of the moose. After an hour or so of circling around the alder the team finally located the moose trail and ran down the mountain to avoid getting caught in the dark, which in an Alaskan summer doesn’t happen often. Finally, the team stumbled out of the alder and back onto the beach. We were bushed and grabbed a bagel for dinner and crawled into our tents and out of the killer bugs.

Joe Wilch and Sarah Appleton standing in front of Casement Glacier.

The next day we stiffly got out of our tents, ate breakfast, and gathered our gear. We set out again on the way of the moose crossing the lakes of the killer giant toads and battling the flesh eating mosquitoes through the moose sandbox and past look out rock. We kept our heads down and practiced the Alaska wave. The Alaska wave can be done in a wide variety of ways, some people prefer to use the back and forth method, others wave with a willow branch, and some swat in a violent fashion. Trudging onward the scientists finally reached the land of the endless outwash plain. They put their heads down and continued to march. Eventually, they reached the corner of bedrock and two large boulders were chosen as a suitable site for a rest and lunch. We continued our procedure that we started in the valley at Wachusett Inlet taking pictures and looking in depth of the sediment in relation to the in situ stumps along the wall of the exposure.

Sarah Appleton standing on the lower tier of a buried forest that is topped by a layer of glacial till.

The sediment features were much less clear at this site most of what we saw was glacial till and bedrock though we did see a section of sediment that appeared to be lake sediments with the trees rooted just below the layers causing up to hypothesize that the trees were growing when a lake came in and flooded them causing them to die and then be run over by a glacial advance. Joe and Sarah hiked up the outwash to further investigate the site. They walked up to the margin of the glacier and discovered even more buried forests up around the corner of the glacier. These were left to be tackled another day, and we made the journey back across the vastly different lands to our base camp.

Joe Wilch pondering the mysteries of Casement Glacier.

Wolf Point

The next day, everyone was exhausted from the brutal hikes to Casement Glacier so we opted to work in a different site to mix it up and allow our legs a chance to heal. Our camp mates, Megan and Ed, said that they saw some old wood in their site, so we decided to go and investigate. Wolf Point is a nice little stream that was across Muir Inlet from our camp. It was an easy walk back to through the alder. The stream was much bigger than the one at their previous site, and required frequent crossing. The first thing we did when we got to the stream was too investigate the old wood. There were several pieces in the stream itself being beaten by the water. After stopping to look at the wood we continued up the stream to catch up with Megan and Ed for lunch. We were nearly there when another stream crossing came up. Dr. Wiles picked his way across it and Sarah was following just behind when SPLASH! Swim number two. She stood up then scurried across the stream. The dry clothes were a relief as was the fact that the rain had finally stopped.

Some old wood mixed in with modern wood caught in the stream.

After lunch we opted to stay and help Megan and Ed with their experiment. We helped them get their water samples and soil samples for the day learning about what they studied and their methods for doing so. All too soon we had completed another field day and it was time to head back to camp. We began to trek back to the beach and were doing well until we came to another stream. Then SPLASH! Sarah’s third swim of the trip. Apparently, you must be so tall to cross the stream and she was just not big enough or more likely needs more practice. This time fortunately, Sarah did not get too wet.

Megan and Ed taking a water sample while Sarah watches in the background.

We pushed onward to the beach and the boat which was floating in the water patiently waiting on our return. Our crew climbed into the boat and sailed back to the beach. Throughout the day we had talked about dinner and decided that we would have quesadillas cooked over the propane stove. We were all really looking forward to this meal. Sarah put in charge of cooking them paired with chicken flavored rice. It turned out to be a great meal that everyone enjoyed while standing around a campfire on the beach as the sun peaked through the gray overcast sky to set behind the mountains. It was a good and relaxing day learning about other research that was done in Glacier Bay.

Large eagle drying out on a small twig.

Bear/Casement

The next day was our last full day at the Forest Creek camp we were set to leave the next morning for Sandy Cove. With the daunting hike to Casement Glacier looming over us we took out time getting ready this morning thought hoping to make somewhat of a decent start. We ate breakfast and gathered our gear that we would need for the day. Once we were ready we piled it up on the beach and went to help get Porkey back into the water. With the five of us pushing the skiff nobody was really watching our surroundings as the metal boat scraped its way down the beach. We successfully managed to get the boat into the water and had turned around to pick up the rest of Megan and Ed’s gear and put it back into the boat. Megan saw it first and called BEAR!

The bear that crept up on us as we pushed Porkey back into the water.

We all froze and began to scan down the beach looking for the bear. Most of us missed it at first because we were looking out down the beach instead of close to us. The bear was less than 100 meters from us and walking right along the shore in our direction. This is one of those moments all the bear safety lectures kick in. We grabbed the remaining gear and grouped together on the beach to make ourselves look bigger. We yelled and clapped our hands or waved trying to get the bear to move away. This bear did not look so good. His fur was dull and shedding out and he was thin. He seemed less than interested in us but gave us a couple more meters space as he walked around us and continued down the shore. He paused every now and again to turn over a good size rock in search of eels to snack on. He took so long and was, fortunately, ignoring us that we began to joke that he was turning over every third rock just to annoy us. Megan and Ed snapped some pictures while we watched and waited for the bear to move on.

The bear as he continued down the beach.

The Wooster team began to make plans on the best way to start our hike that did not encroach on the bear since he was going in the same direction down the beach that we would need to head once it was safe. The bear made it down to the corner of the beach and we decided it was safe to creep back to camp and gather our gear to leave. Our team made it part way up the beach when the bear jerked around and came a few steps in our direction. We froze and looked at each other. The bear apparently had forgotten all about us until we moved again. He took a few more steps in our direction and we quickly walked back down the beach to regroup. Unfortunately, the bear was headed for our camp. We all dashed back to camp and grabbed pots and pans to scare the bear off and protect our turf. This is park policy so that the bears do not get too used to humans and become a more dangerous problem. The bear still did not run from us but did wonder away to the nearby meadow to snack on the grass there. Periodically, he would stand up on his hind legs and look at us over the brush. Finally, he moved on to do whatever bears do in the late morning.

And under rock number three? More eels!

With our last day burning down we took off for Casement Glacier, again following the way of the moose. The hours passed quickly with everyone more on guard looking for bears and any other wildlife that was certainly lurking just beyond the next bush, rock, or tree. Eventually, we plodded to the perceived safety of the endless outwash plain where you can see forever in all directions. We passed by a small kettle lake and suddenly heard something crashing through the alders on the side it. A moose charged out of the brush and galloped away from us. It was neat to get to see one of these animals so close up and a relief that it chose to run away unlike the bear who was content to simply ignore us. We then moved on to lunch in our usual spot with everyone remaining a little jumpy. Before long, it was time to get back to work.

We hiked further down the outcrop and around the side of the glacier. We began to work out way back looking at the stratigraphy in relation to the tree stumps that we saw in place. There were six forests still in place in relation to the small section of lake sediment that we saw there. It was much smaller than the section we studied in Wachusett Inlet. We worked our way back down away from the glacier going over each of the sections. All too soon it was time to return back to camp and we took off on the brutal hike back.

McBride Glacier

The next day was bright sunny and clear giving us an excellent view of the beautiful coastal mountains across from our camp at Forest Creek. We got up ate breakfast and quickly tore down camp to be ready for the arrival of the Capeland which was supposed to arrive at 10 am and we had a bit of a leisurely morning. We loaded our gear and then we headed to McBride Inlet with a team that was tearing down a climate station there.

Three Wooster geologists mugging for the camera in front of McBride Glacier.

McBride Inlet is the home of a tidewater glacier with the same name. We hiked into the glacier after the Capeland dropped us off along the steep shoreline. The shore and inlet were littered with icebergs of all sizes that we all enjoyed taking photographs with and of. It took about an hour to hike in to the knob where we could see the glacier. Here we admired the glacier and ate our lunches while Nick Wiesenberg and Dan Lawson got to work tearing down the climate station. We did not get to see any glacial calving while we watched the glacier just admired and enjoyed the view. Instead, we watched the seals down in the inlet sun bathing on the icebergs and the Kittiwakes swoop and fly around their nesting site on the opposite cliff.

Seals sun bathing on icebergs in McBride Inlet.

Once the team had torn down the climate station we headed back to the beach and the waiting Capeland pausing to occasionally take pictures of the ice. Once back on the boat we swung by the Forest Creek camp to pick up Porkey and then we were off to Sandy Cove raft to drop of Dr. Wiles and Sarah Appleton who would be hiking up to a refugia site on Mount Wright to do some coring of the old trees there. A refugia is a forest of trees that were not run over during the last glaciations and are very old in age relative to the other trees which are moving back into the bay from the coast.

Shopping for icebergs?

After sleeping in a tent for eight days the Sandy Cove raft seemed luxurious with its bunk beds and small kitchenette. The rest of the day was spent on the raft relaxing and preparing for the long days hike up onto the ridge behind Mount Wright.

Sandy Cove Raft!

Mt Wright/Sandy Cove

Early in the morning Dr. Wiles and Sarah Appleton began the climb up the ridge to the Mount Wright refugia. The hike was long and intense walking first through the lowland forest, crossing a bog, and then crashing through the brush on the way up the mountain to the old growth forest. The day was bright sunny and clear which made for beautiful conditions to hike.

View of Beartrack Mountain from the back porch of the Sandy Cove raft.

We hiked up to the upper tree line for a better view. Once at the top we paused to take in the beauty that surrounded them and pictures.

View from the top of the third ridge on Mount Wright!

We sat for a time and rested, overlooking the ground just covered and spotted something gray darting among the patches of green in the snow. Once the gray blur paused to sniff our tracks and we realized it was a wolverine. The wolverine began to follow our tracks back the way we had come. This was sort of frightening to see it track us and to walk down and see its tracks next to ours.

The Wolverine tracking us back the way we had come.

We headed back down to the refugia site and got to work coring trees. Several hours were spent coring trees in the beauty of the forest. All too soon it was time to slide back down the hill through the raspberries and devils club to the shore where we had parked Porkey on loan to us from Megan and Ed. We rowed across the water to the raft and dinner.

The refugia on the ridge behind Mt. Wright in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Alaska.

The next day we laid out our gear to dry and updated our field notes from the day before. The Capeland picked us up and took us back to Gustavus where we loaded our gear up and went to research housing. There we unpacked our personal belongings, took a much needed shower, and met the other scientists staying there as well. We then had a spaghetti dinner courtesy of Nick and went to bed.

Mendenhall

After a great time in Gustavus it was time to fly back to Juneau for a day and a half before we flew home. Saturday morning we boarded Fjord Flying and flew to Juneau.

The plane in which we returned to Juneau.

Once in Juneau we helped to unload our gear from the plane and out into the rental car. From there we went to our favorite Juneau eatery, Donna’s, for breakfast for lunch. After a great and satisfying meal we went to find a place to camp at the Mendenhall campgrounds. Nick and Dr. Wiles carefully picked out the perfect campsite for us to stay. It was lovely with the lake just behind us through the trees. We set up out tents all in a row and set off on a hike to the Mendenhall Glacier!

Mendenhall Glacier in Juneau, Alaska.

We chose to hike the west side trail and go out onto the glacier. The hike was a breeze after all the back country hiking we had done in Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. There was a trail that had good footing and a hand rail when the trail narrowed on an edge. After hiking for a while we made it to the glacier. The cool glacier breeze was refreshing as we cooled off from our hike and explored the glacier, the surrounding bedrock, phyllite, and glacial till. Within the glacial till we were able to find old logs that had been run over by the glacier in the past. We began to wonder about their age and their story. Another student’s future IS???

Sarah Appleton and Nick Wiesenberg hiking on Mendenhall Glacier.

Once our curiosity had been thoroughly sparked we began to hike back down the trail to camp. That night we ate a wonderful meal prepared by Nick over the campfire of bratwursts, complete with onions and green peppers, potato chips, and orange juice followed by a delicate desert of ‘smores made with peanut butter cups or regular chocolate depending on your taste. A great day indeed!

Sarah Appleton and Nick Wiesenberg exploring the Mendenhall Glacier.

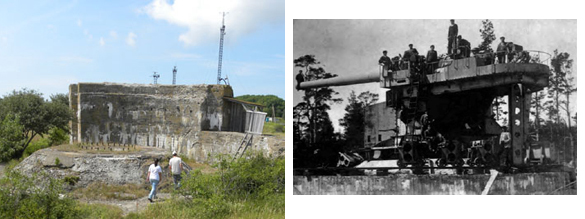

KURESSAARE, ESTONIA–Editor’s note: The Wooster Geologists in Estonia found enough material, and had enough time, to write abstracts for posters at the Geological Society of America Annual Meeting in Minneapolis this October. The following is from student guest blogger Rachel Matt in the format required for GSA abstracts:

KURESSAARE, ESTONIA–Editor’s note: The Wooster Geologists in Estonia found enough material, and had enough time, to write abstracts for posters at the Geological Society of America Annual Meeting in Minneapolis this October. The following is from student guest blogger Rachel Matt in the format required for GSA abstracts: