WOOSTER, OHIO–The cheerful group above is the Wooster Geology Club in our traditional start of the year group photograph. (The image was kindly taken by Danielle Reeder.) We are fewer than usual because an unprecedented number of our geology majors are overseas on off-campus adventures (seven juniors) and our beloved petrologist Meagen Pollock is on a semester research leave. An addition to our crew this year is the man in the upper left with a beard. He is Matt Curren, our new geological technician.

WOOSTER, OHIO–The cheerful group above is the Wooster Geology Club in our traditional start of the year group photograph. (The image was kindly taken by Danielle Reeder.) We are fewer than usual because an unprecedented number of our geology majors are overseas on off-campus adventures (seven juniors) and our beloved petrologist Meagen Pollock is on a semester research leave. An addition to our crew this year is the man in the upper left with a beard. He is Matt Curren, our new geological technician.

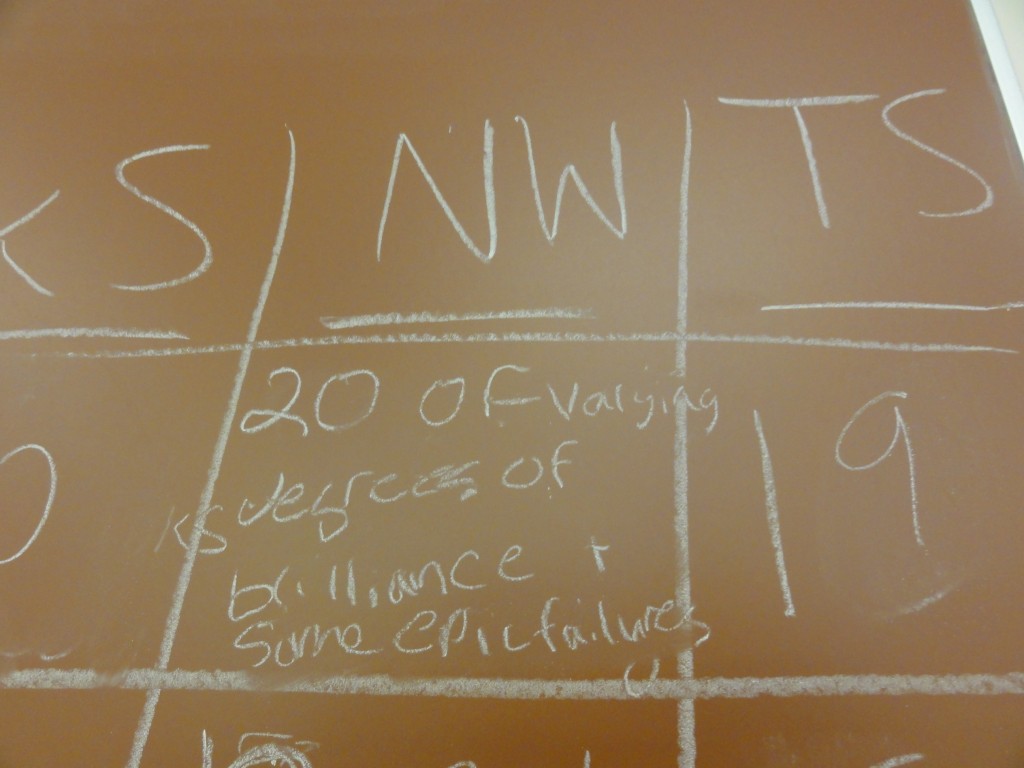

Here you can see happy students in the 8:00 a.m. Invertebrate Paleontology course enjoying their first taste of taxonomic rules and the problem of species. Or maybe they’re grinning because they just learned there is not a quiz this morning?

Here you can see happy students in the 8:00 a.m. Invertebrate Paleontology course enjoying their first taste of taxonomic rules and the problem of species. Or maybe they’re grinning because they just learned there is not a quiz this morning?

There are two significant changes in Scovel Hall for this year. We have a new X-Ray Laboratory under the supervision of Dr. Pollock, complete with a “clean room” for wet chemistry. (I know what the alumni are thinking: A clean room in Scovel? But yes, it really is!) We also have fancy new (and wonderfully silent) computer projection systems in our classrooms, as seen below. We are now very far beyond those old 35 mm slide projectors I grew up with.

Our courses have detailed webpages that you are encouraged to visit. You may also want to see our list of Geology Club events, including Independent Study presentations and outside speakers. Finally, you can follow this link to pdf versions of our annual reports, including our report for this past year and summer (see cover below). Patrice Reeder works very hard to produce these high quality documents.

Our courses have detailed webpages that you are encouraged to visit. You may also want to see our list of Geology Club events, including Independent Study presentations and outside speakers. Finally, you can follow this link to pdf versions of our annual reports, including our report for this past year and summer (see cover below). Patrice Reeder works very hard to produce these high quality documents.

It is going to be another eventful year for the Wooster Geologists. We again thank the generations that have gone before us to build this department, and the alumni and friends who support us so faithfully.

It is going to be another eventful year for the Wooster Geologists. We again thank the generations that have gone before us to build this department, and the alumni and friends who support us so faithfully.