Yes, that “Recent” in the title was a clue that these are not actually fossils, but the little beauties fit the spirit of our series. This is sand from an unknown island beach in southern Japan. The spotted star-shaped grains are the foraminiferan Baculogypsina sphaerulata (Parker & Jones, 1860). They occur by the billions in tropical and sub-tropical parts of the Pacific Ocean.

Yes, that “Recent” in the title was a clue that these are not actually fossils, but the little beauties fit the spirit of our series. This is sand from an unknown island beach in southern Japan. The spotted star-shaped grains are the foraminiferan Baculogypsina sphaerulata (Parker & Jones, 1860). They occur by the billions in tropical and sub-tropical parts of the Pacific Ocean.

Foraminifera are single-celled organisms that often build shells (tests) of calcite and other materials. They have a long fossil record, and we know their evolutionary history in great detail. Foraminifera are thus excellent index fossils for correlating rock units and estimating geological time relationships.

Foraminifera are single-celled organisms that often build shells (tests) of calcite and other materials. They have a long fossil record, and we know their evolutionary history in great detail. Foraminifera are thus excellent index fossils for correlating rock units and estimating geological time relationships.

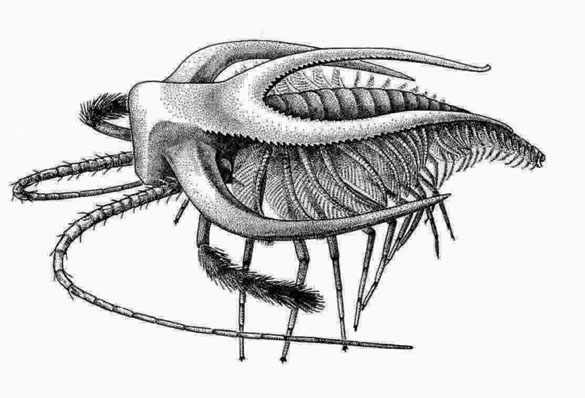

Baculogypsina sphaerulata collected on the famous HMS Challenger expedition of 1873-1876. Image from Brady (1884).

Baculogypsina sphaerulata collected on the famous HMS Challenger expedition of 1873-1876. Image from Brady (1884).

Baculogypsina sphaerulata is an especially interesting foraminiferan. It has a radial canal system that gives it a characteristic star shape. Like many other larger foraminiferans, they have other organisms living inside their tissues called endosymbionts. Here the endosymbionts are pennate (feather-like) diatoms (which was news to me). Diatoms are photosynthetic so they require sunlight to make their carbohydrates. They cluster next to the most transparent parts of the Baculogypsina test interiors, using them like windows to catch some rays. The diatoms release carbohydrate metabolites and oxygen which are used by the host foraminiferan, completing the mutually-beneficial symbiotic relationship.

References:

Brady, H.B. 1884. Report on the Foraminifera dredged by H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873-1876. Report of the scientific results of the voyage of H.M.S. Challenger, 1873-1876, Zoology 9: 1-814.

Hyams-Kaphzan, O. and Lee, J.J. 2008. Cytological examination and location of symbionts in “living sands” — Baculogypsina. Journal of Foraminiferal Research 38: 298-304.

Lee, J.J., Faber, W.W., Nathanson, B., Roettger, R., Nishihira, M. and Krueger, R. 1993. Endosymbiotic diatoms from larger Foraminifera collected in Pacific habitats. Symbiosis 14: 265-281.

Lee, J.J., Morales, J., Symons, A. and Hallock, P. 1995. Diatom symbionts in larger foraminifera from Caribbean hosts. Marine Micropaleontology 26: 99-105.

Röttger, R. and Krüger, R. 1990. Observations on the biology of Calcarinidae (Foraminiferida). Marine Biology 106: 419-425.