Please say hello to Pierrella larsoni Wilson & Taylor 2012 — a new genus and species of ctenostome bryozoan from the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian-Maastrichtian) Pierre Shale of Wyoming and South Dakota. I imagine it as a graceful little thing spreading delicately through the dark interiors of baculitid ammonite conchs on a muddy Cretaceous seafloor. Above is a fossil of Baculites formed when sediment filled the shell and lithified. The shell itself dissolved away, leaving the internal mold of rock (or steinkern) as a kind of cast of the interior. (But don’t ever call it a “cast”!) Pierrella larsoni encrusted the inside surface of Baculites and is thus preserved as a series of connected teardrops on the outside of the internal mold. The specimen is from Heart Tail Ranch, South Dakota, and the scale bar is 10 mm. (Baculites was described in an earlier Fossil of the Week post.)

Please say hello to Pierrella larsoni Wilson & Taylor 2012 — a new genus and species of ctenostome bryozoan from the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian-Maastrichtian) Pierre Shale of Wyoming and South Dakota. I imagine it as a graceful little thing spreading delicately through the dark interiors of baculitid ammonite conchs on a muddy Cretaceous seafloor. Above is a fossil of Baculites formed when sediment filled the shell and lithified. The shell itself dissolved away, leaving the internal mold of rock (or steinkern) as a kind of cast of the interior. (But don’t ever call it a “cast”!) Pierrella larsoni encrusted the inside surface of Baculites and is thus preserved as a series of connected teardrops on the outside of the internal mold. The specimen is from Heart Tail Ranch, South Dakota, and the scale bar is 10 mm. (Baculites was described in an earlier Fossil of the Week post.)

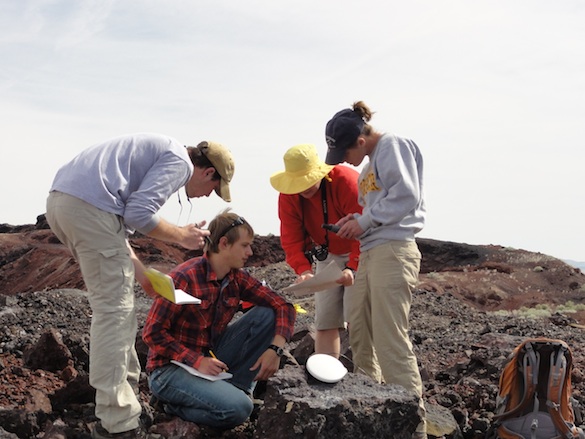

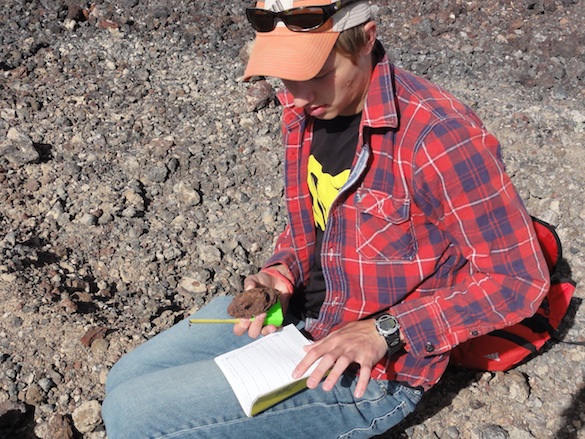

My friend Paul Taylor (The Natural History Museum, London) and I had a wonderful field trip to South Dakota and Wyoming in June 2008. We were accompanied by my ace student John Sime (who is a spectacular field paleontologist) and greatly helped by the distinguished paleontologist and ammonite expert Neal Larson (Black Hills Institute of Geological Research), Bill Wahl (Wyoming Dinosaur Center), and Mike Ross, an avid amateur paleontologist in Casper, Wyoming. We also had assistance from Walter Stein (PaleoAdventures) and the enthusiastic and knowledgeable amateur paleontologist Jamie Brezina. You can see some images from our trip here.

The primary purpose of our expedition was to find and study Late Cretaceous bryozoans. Our paper describing this work has now appeared in a special volume on bryozoan research. The specimen above on the left is from Red Bird, Wyoming, and the one on the right is from the Heart Tail Ranch in South Dakota. The scale bars are 10 and 5 mm respectively.

The primary purpose of our expedition was to find and study Late Cretaceous bryozoans. Our paper describing this work has now appeared in a special volume on bryozoan research. The specimen above on the left is from Red Bird, Wyoming, and the one on the right is from the Heart Tail Ranch in South Dakota. The scale bars are 10 and 5 mm respectively.

Above is a typical example of the Pierre Shale exposures we worked with on this trip. This particular shot is from the Chance Davis Ranch in South Dakota, but they all looked pretty much the same. We crouched down and scanned miles of “outcrop” like this, picking fossils up from the ground.

Above is a typical example of the Pierre Shale exposures we worked with on this trip. This particular shot is from the Chance Davis Ranch in South Dakota, but they all looked pretty much the same. We crouched down and scanned miles of “outcrop” like this, picking fossils up from the ground.

Finding ctenostome bryozoans preserved like this is unusual. They did not (and do not today) have calcareous skeletons. These Pierre specimens were somehow preserved as the internal molds formed, most likely through some process of early cementation of the mud. I described this fossil fauna and its preservation in an earlier post from a GSA meeting.

Pierrella is named after the Pierre Shale; larsoni after our colleague Neal Larson. It is nice to have locked into the name direct reminders of that delightful summer under those big Western skies.

Reference:

Wilson, M.A. and Taylor, P.D. 2012. Palaeoecology, preservation and taxonomy of encrusting ctenostome bryozoans inhabiting ammonite body chambers in the Late Cretaceous Pierre Shale of Wyoming and South Dakota, USA. In: Ernst, A., Schäfer, P. and Scholz, J. (eds.) Bryozoan Studies 2010; Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences 143: 399-412.