One common frame used to introduce landforms in introductory Geology courses is the idea of constructive and destructive forces that create and change them. (See, for example some K-12 resources here and here.) Constructive processes like the the deposition of sediment and extrusion of lava build landforms by adding material at the surface. Destructive processes like weathering and erosion and explosive volcanism shape the surface by removing material.

If you go to the Paradise Visitor Center in Mount Rainier National Park, you can observe this dichotomy at work just by comparing the north and south. Looking to the north is the park’s namesake: Mount Rainier. The smooth, rounded shape of this composite stratovolcano is primarily the result of layered ash, rubble, and lava over the past 500,000 to a million years, piling up over 14,000 ft high (NPS). There are glaciers eroding the flanks of Mount Rainier, but the recent volcanism of the past few thousand years means the overall shape is more reflective of volcanism than glaciation.

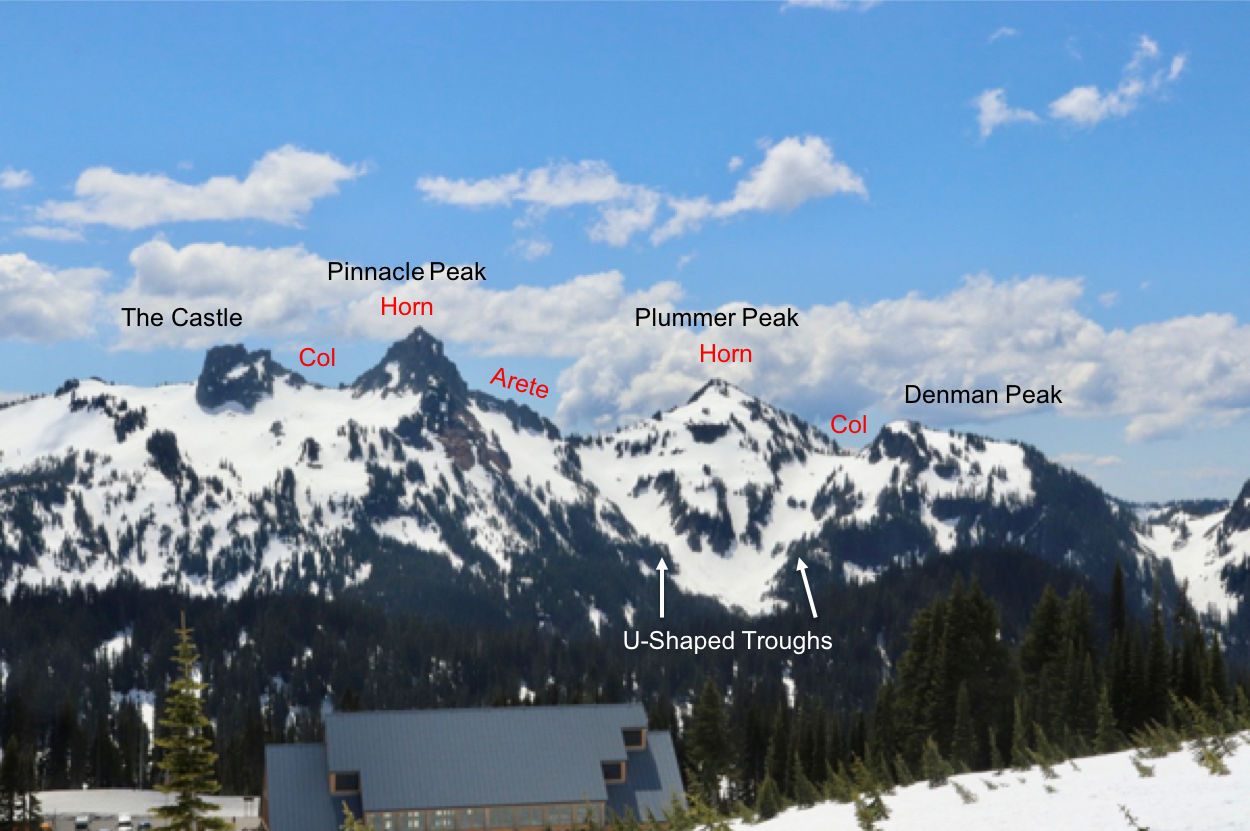

Contrast this with the view to the south. Rather than a single smooth and rounded profile, the Tatoosh Range is characterized by several jagged peaks with names like “The Castle” and “Pinnacle Peak”. This mountain range is the result of extensive weathering of an ancient pluton, which was originally emplaced in the Miocene (14 million years ago; USGS 1963; Mattinson 1977). The Tatoosh pluton was exposed at the surface and actively eroded by Pleistocene glaciers long before Mount Rainier existed. With millions of years of erosion at work, destructive forces are more obvious in the Tatoosh Range than on Mount Rainier. It displays classic glacial features like the horn of Pinnacle Peak, the col between Plummer Peak and Denman Peak, and the converging U-shaped troughs below Plummer Peak.