A geoheritage site is a location where the geological features are worth preserving for scientific and cultural reasons. It is a relatively new term dating back to the 1990s. The purpose of designating a geoheritage site is to mark it as special to protect it from degradation or destruction. The label has no legal status (yet), but it is a start on conserving important geological resources with value beyond the real estate they occupy or resources they contain. There is even now a journal titled Geoheritage for publishing accounts of these places.

My friend Olev Vinn of the University of Tartu suggested that two locations on the Sõrve Peninsula of Saaremaa Island, Estonia, should be designated geoheritage sites for their remarkable Upper Silurian rocks and fossils. He put together a team of paleontologists to work on the paper, and I was fortunate to join them. Olev and I have worked together in Estonia since 2006, and have had many colleagues and Wooster students with us since then (including Professor Bill Ausich of The Ohio State University since 2009).

Our paper has now appeared in Geoheritage. Here is the abstract —

The Upper Silurian exposures on Saaremaa Island, mostly represented by small coastal cliffs, are the best in Estonia. Among these exposures are two coastal cliffs that are in many ways unique. The Pridoli crinoid fauna at Kaugatuma and the Ohesaare cliffs contains several endemic genera such as Methabocrinus, Saaremaacrinus, and Velocrinus, which occur exclusively in the Pridoli of Saaremaa Island. These localities have great potential for future studies of crinoid paleobiology and paleoecology. The fossil symbiotic associations have high value for studies devoted to evolutionary paleoecology. The Kaugatuma and Ohesaare cliffs yield the only symbiotic associations that are known from the Pridoli worldwide. Both cliffs are also famous localities of early vertebrates. The Kaugatuma and Ohesaare cliffs are places of scenic beauty, and the rarity of fossiliferous Pridoli outcrops in the Baltic Sea region makes these cliffs important destinations for European geotourism.

The image at the top of this post is of the Kaugatuma-Lõo ripple-mark coast on the Sõrve Peninsula, one of my favorite geological places. Bedding-plane exposures like this are unusual on the island. This one has numerous crinoid holdfasts (functionally “roots”) and stems of crinoids, many quite large. These are the Middle Äigu Beds of the Kaugatuma Formation. It was essentially a well-preserved crinoid forest on the Silurian seafloor. Palmer Shonk (’10) did his Wooster Senior Independent Study field descriptions and collections here. (He is in the yellow shirt above.) This site also has historical importance as the location of a WWII Soviet amphibious landing in November 1944.

Crinoid holdfast in the Middle Äigu Beds of the Kaugatuma Formation on the Kaugatuma-Lõo ripple-mark coast. This structure is like the tap root of a tree. It penetrated the sediment, tapering downwards, and produced lateral branches (radices) which held the crinoid in place in the energetic marine environment.

Another view of the cross-bedded Äigu Beds of the Kaugatuma Formation on the Kaugatuma-Lõo ripple-mark coast.

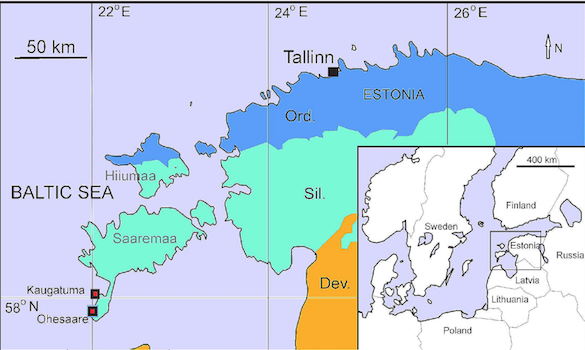

The two geoheritage sites on Saaremaa Island, Estonia. (From Figure 1 of the Geoheritage paper.)

The two geoheritage sites on Saaremaa Island, Estonia. (From Figure 1 of the Geoheritage paper.)

This project brings back many delightful memories of fieldwork in Estonia. In fact, we still continue to study our collections for additional research projects. Thank you, Olev, for your leadership over the past two decades!

Reference:

Vinn, O., Wilson, M.A., Isakar, M. and Toom, U. 2024. Two high value geoheritage sites on Sõrve Peninsula (Saaremaa Island, Estonia): a window to the unique Late Silurian fauna. Geoheritage (in press) https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-024-00957-7