SCARBOROUGH, ENGLAND (June 7, 2015) — This steep and muddy slope may not look like much, but it is the man exposure of the famous Speeton Clay, a Lower Cretaceous unit rich with fossils. Team Yorkshire started here (N 54.16654°, W 00.24567°) this morning to continue our reconnaissance of the local geology. The weather could not have been better. (I can only imagine what this sediment is like when wet!)

SCARBOROUGH, ENGLAND (June 7, 2015) — This steep and muddy slope may not look like much, but it is the man exposure of the famous Speeton Clay, a Lower Cretaceous unit rich with fossils. Team Yorkshire started here (N 54.16654°, W 00.24567°) this morning to continue our reconnaissance of the local geology. The weather could not have been better. (I can only imagine what this sediment is like when wet!)

The Speeton Clay is quite mobile, with slips and land slippages very common along its coastal exposure. This is a World War II pillbox, part of the sea defenses of Britain, making its way down slope on the clay. On the shore itself are bits of previous WWII concrete installations that are now on the beach.

The Speeton Clay is quite mobile, with slips and land slippages very common along its coastal exposure. This is a World War II pillbox, part of the sea defenses of Britain, making its way down slope on the clay. On the shore itself are bits of previous WWII concrete installations that are now on the beach.

After collecting dozens of belemnites from the Speeton Clay for future research, we visited an exposure of the Red Chalk (Hunstanton Formation), which has smaller belemnites of a different genus.

After collecting dozens of belemnites from the Speeton Clay for future research, we visited an exposure of the Red Chalk (Hunstanton Formation), which has smaller belemnites of a different genus.

If we continued to the south we would have met these imposing cliffs of chalk, the northern part of the series of white coastal chalks that extends south past Dover. Seabirds swirled around them in the thousands this morning.

If we continued to the south we would have met these imposing cliffs of chalk, the northern part of the series of white coastal chalks that extends south past Dover. Seabirds swirled around them in the thousands this morning.

While walking back to our car, Paul Taylor showed Meredith Mann and Mae Kemsley various intertidal organisms exposed on the broad beach beneath the Speeton Cliffs.

While walking back to our car, Paul Taylor showed Meredith Mann and Mae Kemsley various intertidal organisms exposed on the broad beach beneath the Speeton Cliffs.

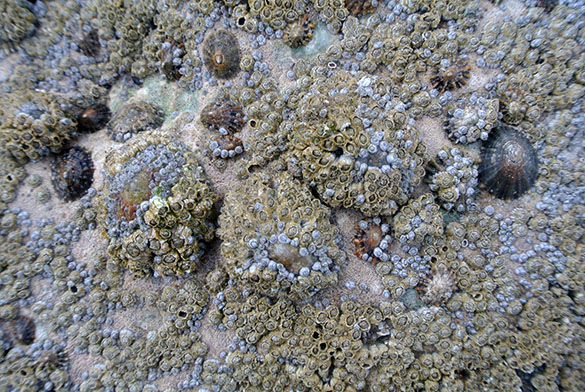

At a certain mid-tide level, the boulders on the beach were entirely covered with tiny barnacles. The rock itself is completely hidden.

At a certain mid-tide level, the boulders on the beach were entirely covered with tiny barnacles. The rock itself is completely hidden.

Here is a closer view of the rock surface. The oldest barnacles are greenish, the younger are gray. You can easily see several small limpets, but do you see the three large individuals in the center? They are camouflaged by their covering of barnacles.

Here is a closer view of the rock surface. The oldest barnacles are greenish, the younger are gray. You can easily see several small limpets, but do you see the three large individuals in the center? They are camouflaged by their covering of barnacles.

For a Sunday afternoon on such a nice day, we were pleased to see very few people on large stretches of the beach along the Speeton Cliffs. We had much more company later in the day.

For a Sunday afternoon on such a nice day, we were pleased to see very few people on large stretches of the beach along the Speeton Cliffs. We had much more company later in the day.

In the afternoon we visited Filey Brigg for a look at parts of the Coralline Oolite Formation (Upper Jurassic, Oxfordian; N 54.21674°, W 00.26922°). We found the Hambleton Oolite Member very accessible and with a good number of fossils that could be collected. We are here looking at the “Upper Leaf” of the unit.

In the afternoon we visited Filey Brigg for a look at parts of the Coralline Oolite Formation (Upper Jurassic, Oxfordian; N 54.21674°, W 00.26922°). We found the Hambleton Oolite Member very accessible and with a good number of fossils that could be collected. We are here looking at the “Upper Leaf” of the unit.

Down on the Brigg itself we saw these massive overturned boulders of the Birdsall Calcareous Grit Member with spectacular examples of the trace fossil “boxwork” Thalassinoides. These fossil burrow systems were made by shrimp, probably of the callianassid variety.

Down on the Brigg itself we saw these massive overturned boulders of the Birdsall Calcareous Grit Member with spectacular examples of the trace fossil “boxwork” Thalassinoides. These fossil burrow systems were made by shrimp, probably of the callianassid variety.

Sometimes the sediment between the infilled Thalassinoides tunnels was washed away, leaving this beautiful network in full relief.

Sometimes the sediment between the infilled Thalassinoides tunnels was washed away, leaving this beautiful network in full relief.

On the north side of Filey Brigg we could continue to follow the Upper Leaf of the Hambleton Oolite Member. The exposure is very good and well above the high tide. The access to this place, though, requires a low tide like we had this afternoon.

On the north side of Filey Brigg we could continue to follow the Upper Leaf of the Hambleton Oolite Member. The exposure is very good and well above the high tide. The access to this place, though, requires a low tide like we had this afternoon.

At this site on the north side of Filey Brigg (N 54.21823°, W 00.26908°) we can get to the Lower Leaf of the Hambleton Oolite Member, with the Birdsall Calcareous Grit Member just above. Again, the Hambleton has many fossils that can be collected. If you look at the undersurface of the yellowish rock above our field party, you may be able to make out the Thalassinoides trace fossils. We can thus place the loose blocks with this distinctive trace fossil in their original stratigraphic position.

At this site on the north side of Filey Brigg (N 54.21823°, W 00.26908°) we can get to the Lower Leaf of the Hambleton Oolite Member, with the Birdsall Calcareous Grit Member just above. Again, the Hambleton has many fossils that can be collected. If you look at the undersurface of the yellowish rock above our field party, you may be able to make out the Thalassinoides trace fossils. We can thus place the loose blocks with this distinctive trace fossil in their original stratigraphic position.

Another delightful field day. One more expedition tomorrow, and then we decide on the specific student projects.