Guest Blogger: Audrey Steiner-Malumphy

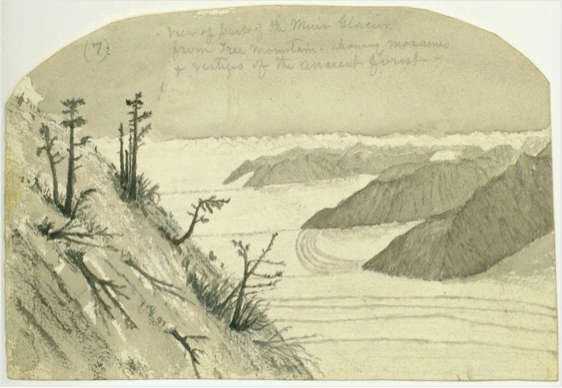

In 2011, Dr. Wiles and his advisees Lauren Vargo and Jennifer Horton cored dozens of trees from Tree Mountain in Alaska’s Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. Muir Glacier is located northwest of this mountain, named after the esteemed naturalist and preservationist John Muir.

Muir first traveled to the area in 1879 with a particular interest in Alaska’s glaciers. He returned many times, continually fine-tuning his preservationist vision while drawing from theistic and transcendentalist ideas to transform the public’s perception of wilderness. Muir’s published works recalling these expeditions sparked national interest in Alaska’s wilderness and its preservation, laying the foundation for environmental debates yet to come.

Though the Tlingit lived in the Glacier Bay region for centuries, and others explored the area before him, Muir was the first distinguished scientist to map it and record his observations.

Above is a present-day map of Glacier Bay, courtesy of Google Earth. Tree Mountain is marked in red on the southern border of Adams Inlet, which feeds into Muir Inlet. Muir Glacier lies at its base. Note the altered position and size of the glacier in comparison to Muir’s map.

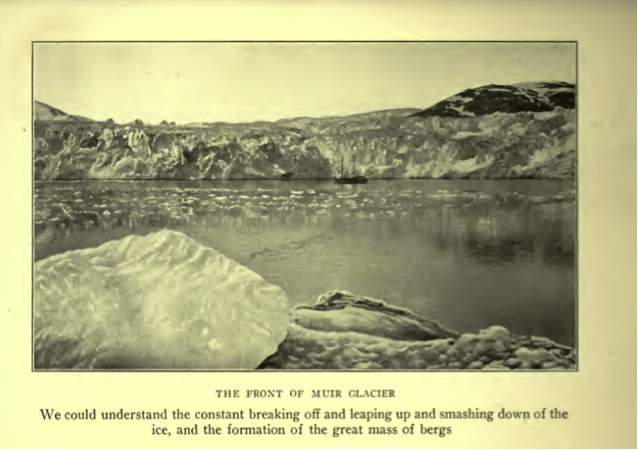

Photographs from the National Snow and Ice Data Center famously portray Muir Glacier’s retreat. Between 1941 (left) and 2004 (right), the tidewater glacier retreated more than seven miles, though it has been rapidly retreating since the end of the Little Ice Age in the mid 1800s.

Muir observed the rapid retreat of glaciers, expressing concern for Alaska’s changing climate and frustration with potential anthropogenic causes, specifically deforestation. In October of his 1879 expedition, he wrote in his journal, “That the climate is warmer is shown by the melting shrinking condition of the glaciers… where formerly much snow fell to thaw off gradually, incessant flood-rains fall, saturating the soil, causing it to decay and become slippery and wash off… It was not in this condition while the forests existed.”

To learn more about the climate in the Glacier Bay area when Muir recorded his observations, I measured the tree-ring widths of the Tree Mountain cores. Twenty of the Tree Mountain samples dated back to the mid 1800s or later, allowing me to compare tree-ring records with John Muir’s notes from his 19th century expeditions.

The growth patterns of tree-rings vary based on the species, age of the tree, and other environmental factors. However, tight growth patterns, representing little growth, are typically an indication of stress. Increased growth usually reflects temperature, precipitation, the availability of nutrients.

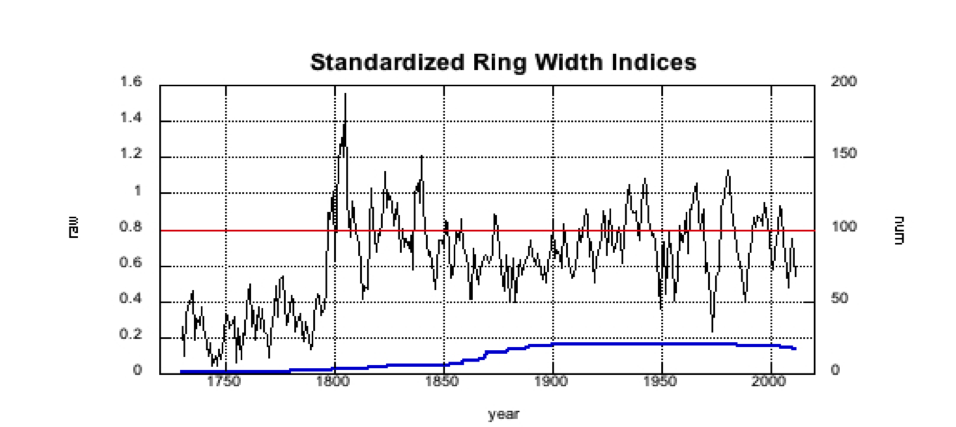

This figure above shows the standardized raw ring widths of the twenty cores from Tree Mountain. The growth trend has been removed. The blue line beneath the raw data represents the number of cores measured each year.

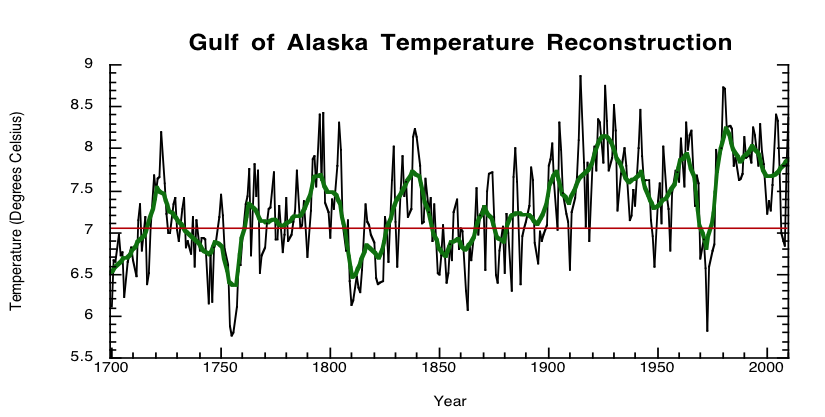

A 2014 study headed by Dr. Wiles provides a chronology and climate reconstruction for the entire Gulf of Alaska over the past 1200 years.

A 2014 study headed by Dr. Wiles provides a chronology and climate reconstruction for the entire Gulf of Alaska over the past 1200 years.

According to my Tree Mountain findings, John Muir’s 19th expeditions in Alaska occurred during a period of gradual warming, aligning with the chronology provided in Dr. Wiles’ study. However, the small Tree Mountain sample size poses difficulties in making significant comparisons, as well as the complexities of the numerous factors that influence both ring width and temperature, which are not accounted for in this post. Further comparisons of the paleoclimate record and the writings of John Muir in Glacier Bay continue..

John Muir has been my hero since high school. Excellent account.