In addition to the summer work described by Lilly Hinkley and Tyrell Cooper, the Wooster Tree Ring Lab is collaborating projects with (1) The Tree Ring Lab of the Johannes Gutenberg-University in Mainz, Germany. This work is part of a project called Monostar (Modelling Non-Stationary Tree growth Responses to global warming) and (2) The University of Alaska – Fairbanks funded by the National Science Foundation, which involves developing long tree-ring records from along the Gulf of Alaska. This post describes some of the sampling aspects of these projects this past summer.

First MONOSTAR sampling: We started in Juneau – here (below, left to right) is Nick Wiesenberg (Wooster), Philipp Romer (Mainz), and Davide Frigo (University of Padova, Italy).

The first tree-ring site was above the Mendenhall Glacier at the East Glacier Site. MONOSTAR sampling is being done across the Northern Hemisphere to determine the whys, hows, wheres and whens of changing tree growth with changing climate. The trees in the background are mountain hemlock with a few Sitka spruce. This is close to a yellow cedar site that we sampled some years ago.

Philipp and Davide with Mendenhall Glacier in the background.

The next stop was Glacier Bay where we flew to Gustavus. The Tlingit Meeting House in Glacier Bay. The totems here in Bartlett Cove look to the east towards Excursion Ridge where the team sampled an Alaska Yellow Cedar and a Shore Pine tree-ring site.

Walking up Excursion Ridge – the first obstacle was a river crossing a bit deeper that our boots, Nick manufactured a bridge for the group.

Philippe shows off a large diameter tree core from an Alaska Yellow Cedar core. After the work with MONOSTAR, we left Bartlett Cove and caught a ride with the Foglark Research Vessel with captain Justin Smith who brought us to the East Arm of Glacier Bay (Muir Inlet).

The Foglark sits offshore after dropping us off with our kayak in Muir Inlet. The mission was to sample wood in fans along the margin of the fiord in the wake of the retreating ice. The priority was to sample wood in the 2000 year old range.

Most of the area we explored over a 9-day period was covered in ice very recently. The map above shows location at the head of Muir Inlet south to McBride Glacier.

In the summer 2023 Muir Glacier (right) is now split into Muir and Morse Glacier (left), which are both terminating on land now, rather than in the ocean (tidewater glaciers).

Landing at the head of Muir Inlet we examined the outwash of the considerable rivers flowing, but no wood was found.

Nick shown scouring the many tributary side valleys that are recently deglaciated – many that were sampled successfully for wood in years past have been scoured of wood, likely due to large rainstorms and mass movements.

The next stop was McBride Glacier. Recent (last 5 years) ice retreat has opened up new landscapes and the potential of buried wood. We know from previous sampling that the wood should be in the 8,000 year old range.

The view into McBride is spectacular.

2020 GoogleEarth image above shows the tidewater McBride Glacier and the 2023 ice margin.

August 2023 ice margin on this GoogleEarth image. The tributary valleys just south of the ice margin have been exposed over the past two years.

To the left and the right of the 2023 ice margin, the two valleys recently exposed by the retreating ice. The valleys align along a fault zone.

Nick is standing on a major sand bar/ delta in the middle of the fiord suggesting the glacier may be grounded now, or is there ice below the sand? It is hard to determine. It may be with the large sediment wedge the glacier will slow its retreat or even advance a bit.

From the mid-fiord sand bar looking downfjord – the two deltas to the left and right are contributing large volumes of sediment to the fan we are standing on.

Nick samples the 8000 year old wood encased in ice-marginal sediments.

An 8000 year old Sitka spruce stump in place – it is reminiscent of a totem.

The North Pacific pours in and out of McBride Inlet twice a day – the navigation is tricky. We look forward to further work on McBride.

The next stop down Muir Inlet was in the shadow of the Nunatak – the wood here is in the critical 2000 year old range (run over by ice 2000 years ago). A Nunatak is a hill/mountain surrounded by ice (from Inuit nunataq).

Nick shows the haul of wood sampled from drainages around the Nunatak.

The final sampling in Muir Inlet was done as we paddled south down Muir Inlet. Here we camped with a spectacular view of Mt. Wright. From previous work we have amazing Mt. Hemlock data from this impressive mountain.

Along the way, Nick stops at a log that we know is about 4000 years old. It may not look like a log but it is a Mt. Hemlock tree with well over 350 rings. We know this as we sampled it last year 2022.

Nick extracts the section.

A panorama of McBride Fiord (right) and Muir Inlet (left) during a flooding tide. We thank The College of Wooster, the National Park Service, the National Science Foundation, and all the students and collaborators who have contributed to this work.

This year’s Paleoecology class field trip was to a familiar place: a roadcut outside Richmond, Indiana, exposing the Whitewater Formation in the gorgeous Upper Ordovician System. We call it the catchy name “C/W-148” (N 39.78722°, W 84.90166°). It was a beautiful sunny August day. Warm and plenty humid, with innumerable sweat bees to keep us company as we collected bags of fossils.

This year’s Paleoecology class field trip was to a familiar place: a roadcut outside Richmond, Indiana, exposing the Whitewater Formation in the gorgeous Upper Ordovician System. We call it the catchy name “C/W-148” (N 39.78722°, W 84.90166°). It was a beautiful sunny August day. Warm and plenty humid, with innumerable sweat bees to keep us company as we collected bags of fossils. Here’s the happy class as we begin the three-hour bus ride to the outcrop. They are all well adapted to school bus travel with their pillows and phones.

Here’s the happy class as we begin the three-hour bus ride to the outcrop. They are all well adapted to school bus travel with their pillows and phones. Once at the outcrop we spread out and began filling bags with fossils. We hadn’t yet finished even our first week in the course before the trip, so the students had little idea what they were collecting other than what we could examine in a preceding lab. In a way this sort of naive collecting produces more diverse assemblages to study back home in Wooster.

Once at the outcrop we spread out and began filling bags with fossils. We hadn’t yet finished even our first week in the course before the trip, so the students had little idea what they were collecting other than what we could examine in a preceding lab. In a way this sort of naive collecting produces more diverse assemblages to study back home in Wooster. Success! Everyone made it home safely, and everyone had a full bag of fossil delights.

Success! Everyone made it home safely, and everyone had a full bag of fossil delights. Once we had the fossils in the lab we could begin the simplest preparation — washing them. Here our TA Hudson Davis shows how it’s done.

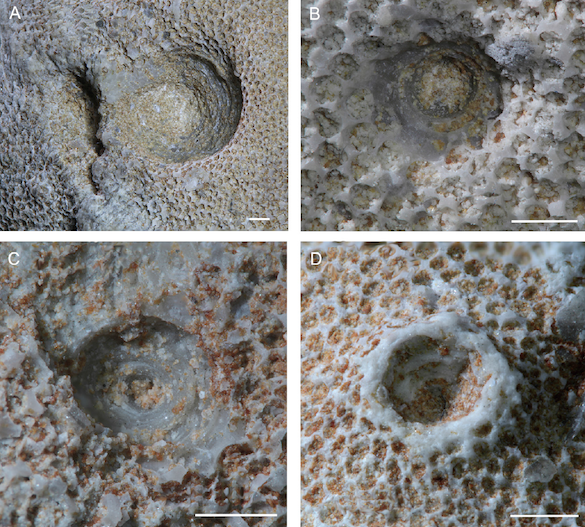

Once we had the fossils in the lab we could begin the simplest preparation — washing them. Here our TA Hudson Davis shows how it’s done. A washed collection from one student. It is great fun looking at 15 such trays at the start to see what treasures we have. Students will be preparing, identifying and interpreting these fossils for the rest of the semester, culminating in a lab report.

A washed collection from one student. It is great fun looking at 15 such trays at the start to see what treasures we have. Students will be preparing, identifying and interpreting these fossils for the rest of the semester, culminating in a lab report. Here’s the class again, this time in our air-conditioned classroom. It’s going to be a great semester of paleoecology at The College of Wooster!

Here’s the class again, this time in our air-conditioned classroom. It’s going to be a great semester of paleoecology at The College of Wooster! [Added on August 29, 2023. All specimens washed! Quite the collection.]

[Added on August 29, 2023. All specimens washed! Quite the collection.]