Several of my colleagues and I have been studying the fossil records of tubeworms for almost three decades now. We find them especially interesting because they are often beautifully preserved on hard substrates like shells, rocks and hardgrounds. They represent a relatively simply paleoecological niche: small sessile benthic filter-feeders. Tubeworms are also systematically diverse and polyphyletic (no common tubeworm ancestor). They show much evolutionary convergence over time between separate groups. One of the most dramatic comparisons (if there is drama in such esoteric topics) is between the extinct microconchids and the extant spirorbin serpulids. Their little shells can be nearly identical, separable primarily bu different skeletal microstructures. Microconchids and spirorbins are in the same ecological niche, but when did the former give way to the latter? We now have new evidence that narrows the time gap between the two clades.

Several of my colleagues and I have been studying the fossil records of tubeworms for almost three decades now. We find them especially interesting because they are often beautifully preserved on hard substrates like shells, rocks and hardgrounds. They represent a relatively simply paleoecological niche: small sessile benthic filter-feeders. Tubeworms are also systematically diverse and polyphyletic (no common tubeworm ancestor). They show much evolutionary convergence over time between separate groups. One of the most dramatic comparisons (if there is drama in such esoteric topics) is between the extinct microconchids and the extant spirorbin serpulids. Their little shells can be nearly identical, separable primarily bu different skeletal microstructures. Microconchids and spirorbins are in the same ecological niche, but when did the former give way to the latter? We now have new evidence that narrows the time gap between the two clades.

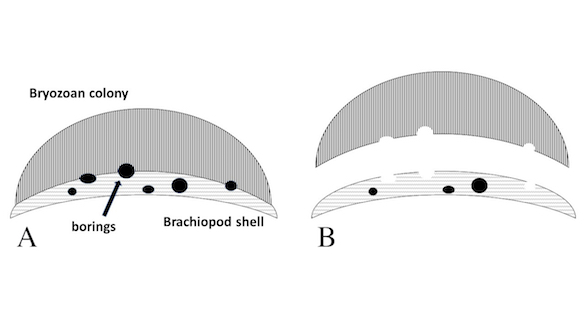

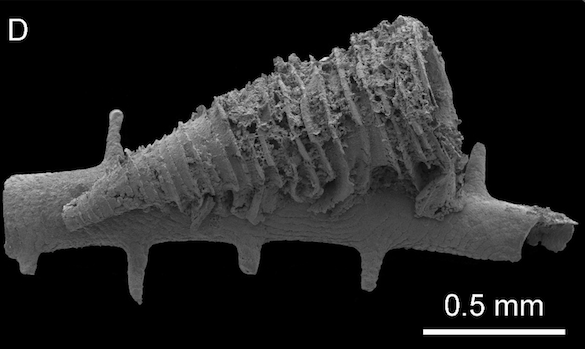

Two years ago I had a look through a set of crinoid columns collected in the Callovian (Middle Jurassic) Matmor Formation of southern Israel. The fantastic fossils in the Matmor have been the basis of many papers (and blog posts) from my research group over the past two decades. (The top image of this post shows some of these fossils in the field. Note the abundant crinoid columns.) I was revisiting these crinoid columns for some crinoid-related idea I’ve now forgotten. Instead, I noticed tiny little spiral tubeworms encrusting some of the crinoids. This was immediately an issue — they were either the youngest microconchids (which are Bathonian, a stage below) or the oldest spirorbins (up until now in the Cretaceous, a system above). They fell into the stratigraphic gap between these groups.

I sent the specimens immediately to my friend and colleague Olev Vinn in Estonia. He determined through analysis of the microstructure that these Callovian tubes were of the earliest spirorbins, and that they represented two new species. We invited two other experts into the project who had their own mysterious Middle Jurassic tubeworms. Our paper has now appeared in the journal PalZ. Here is the abstract —

Two new spirorbin species, Neomicrorbis israelicus sp. nov. and Spirorbis? hagadolensis sp. nov., are here described from the Callovian of Israel, together with two new variations of Neomicrorbis israelicus from the late Bathonian of northern France and Callovian of Madagascar. These are the geologically earliest true Spirorbinae. Our new data, and a literature review of microconchids and early spirorbins, suggest that the ecological switchover from spirorbiform microconchids to spirorbin polychaetes took place in the late Bathonian, and that the spread of spirorbins across the Jurassic and Early Cretaceous seas was rapid. The ecospace of spirally coiled spirorbiform microconchids could thus have been competitively taken over by true spirorbins. The true spirorbin polychaetes may have been ecologically more successful than their Paleozoic analogues – the microconchids. The general rarity of spirorbin-bearing localities in Europe from the Bathonian to Albian supports the hypothesis that the Spirorbinae likely originated in the equatorial Tethys and only occasionally spread to the northern hemisphere seas until the end of the Early Cretaceous. Spirorbins finally became common, diverse and widespread in the northern seas by the Late Cretaceous, and even more so in the Cenozoic.

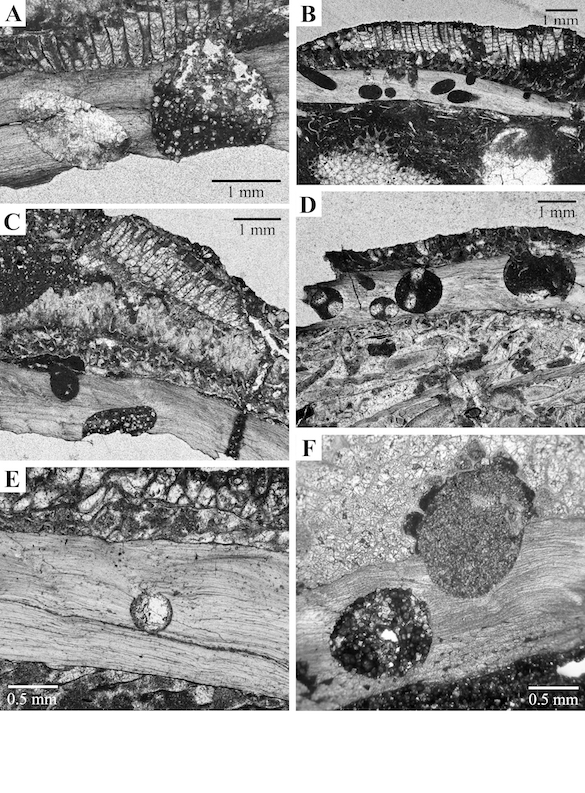

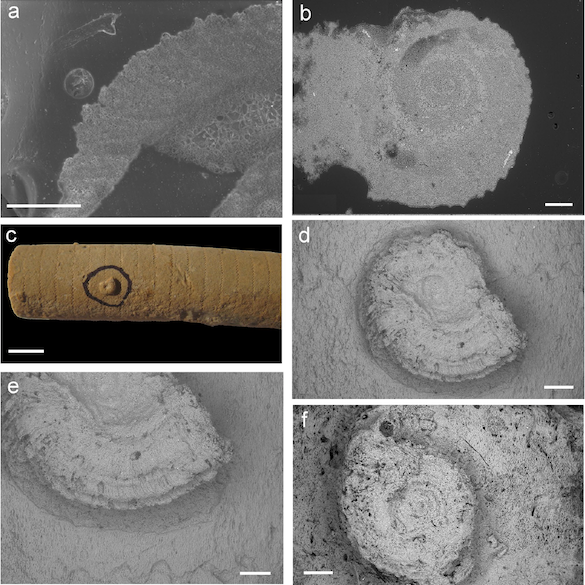

Spirorbins from the Callovian of Hamakhtesh Hagadol, Israel. a Longitudinal section of the tube showing growth lamellae characteristic of the serpulids. b Section through the tube showing open tube origin and lack of protoconch. c Neomicrorbis israelicus sp. nov. encrusting a crinoid stem. d–e Neomicrorbis israelicus sp. nov. (holotype) showing four longitudinal keels. f. Neomicrorbis israelicus sp. nov. (paratype). Scale bars: a, b, e, f 300 um; c 5 mm; d 400 um. (From Figure 1 of Vinn et al., 2024.)

Spirorbins from the Callovian of Hamakhtesh Hagadol, Israel. a Longitudinal section of the tube showing growth lamellae characteristic of the serpulids. b Section through the tube showing open tube origin and lack of protoconch. c Neomicrorbis israelicus sp. nov. encrusting a crinoid stem. d–e Neomicrorbis israelicus sp. nov. (holotype) showing four longitudinal keels. f. Neomicrorbis israelicus sp. nov. (paratype). Scale bars: a, b, e, f 300 um; c 5 mm; d 400 um. (From Figure 1 of Vinn et al., 2024.)

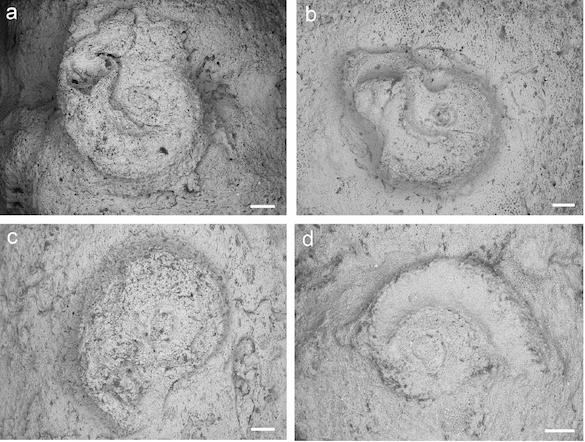

a–d Spirorbis? hagadolensis sp. nov. from the Callovian of Hamakhtesh Hagadol, Israel. Note lack of the longitudinal keels and rounded tube cross-section. Scale bars: a 400 um; b 200 um; c, d 300 um. (From Figure 4 of Vinn et al., 2024.)

a–d Spirorbis? hagadolensis sp. nov. from the Callovian of Hamakhtesh Hagadol, Israel. Note lack of the longitudinal keels and rounded tube cross-section. Scale bars: a 400 um; b 200 um; c, d 300 um. (From Figure 4 of Vinn et al., 2024.)

I tell my students to always look for anomalies in scientific observations and data. There are stories to be told when you find something out of place. This is also a case of specimens in a collection being useful for projects unknown at the time they were gathered. This is one reason why have museums to preserve items for unknown future discoveries. The spirobin tubeworms here are certainly not charismatic fossils, but they nonetheless fill in an important evolutionary gap.

Reference:

Vinn, O. Wilson, M.A., Jäger, M. and Kočí, T. 2024. The earliest true Spirorbinae from the late Bathonian and Callovian (Middle Jurassic) of France, Israel and Madagascar. PalZ (in press) https://doi.org/10.1007/s12542-023-00681-7