On the second floor of Wooster’s Scovel Hall, in a room behind the main teaching laboratory, are six cabinets completely full of labelled rocks and fossils (see below). There is even an additional set of specimens too large for the cabinets stored under the eaves in the attic space on the third floor, and in various other cabinets are suites of fossil hard substrates. This is The College of Wooster’s carbonate hardground collection, unique in the world for its size and diversity.

On the second floor of Wooster’s Scovel Hall, in a room behind the main teaching laboratory, are six cabinets completely full of labelled rocks and fossils (see below). There is even an additional set of specimens too large for the cabinets stored under the eaves in the attic space on the third floor, and in various other cabinets are suites of fossil hard substrates. This is The College of Wooster’s carbonate hardground collection, unique in the world for its size and diversity.

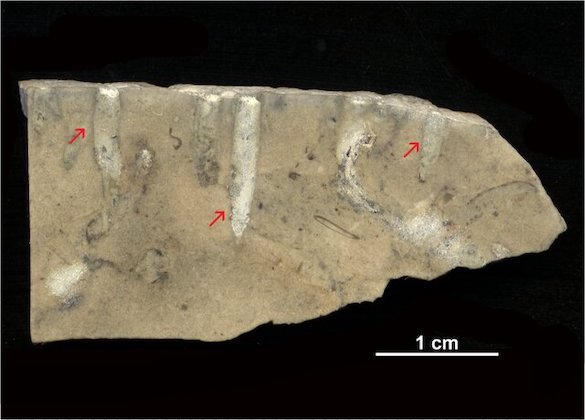

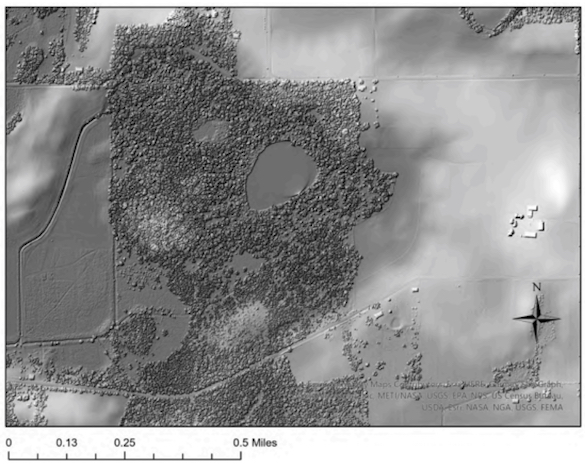

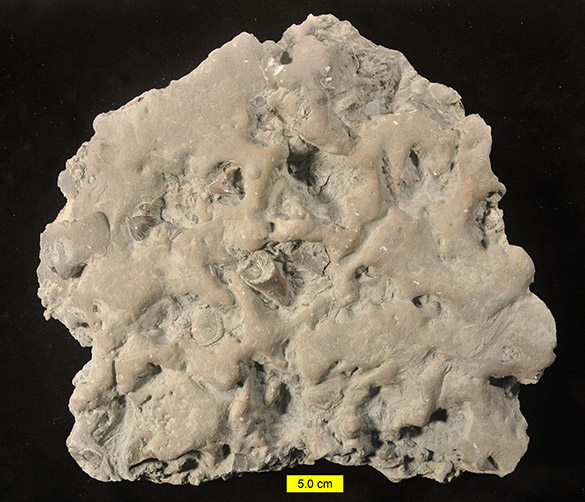

Carbonate hardgrounds are rock surfaces that were once cemented calcareous sediment layers on seafloors (Palmer, 1982; Wilson and Palmer, 1992). The top image of this post shows a hardground from the Upper Ordovician of southwestern Ohio. It is a limestone distinguished by a surface with encrusting organisms, borings, and nestlers in cavities showing it was an ancient lithified seafloor — a rocky substrate in a shallow Ordovician sea. The cementation of carbonate hardgrounds is synsedimentary, meaning they were formed by precipitation of carbonate crystals between sediment grains on the seafloor itself, not long afterwards following deep burial (Erhardt et al., 2020).

Carbonate hardgrounds are rock surfaces that were once cemented calcareous sediment layers on seafloors (Palmer, 1982; Wilson and Palmer, 1992). The top image of this post shows a hardground from the Upper Ordovician of southwestern Ohio. It is a limestone distinguished by a surface with encrusting organisms, borings, and nestlers in cavities showing it was an ancient lithified seafloor — a rocky substrate in a shallow Ordovician sea. The cementation of carbonate hardgrounds is synsedimentary, meaning they were formed by precipitation of carbonate crystals between sediment grains on the seafloor itself, not long afterwards following deep burial (Erhardt et al., 2020).

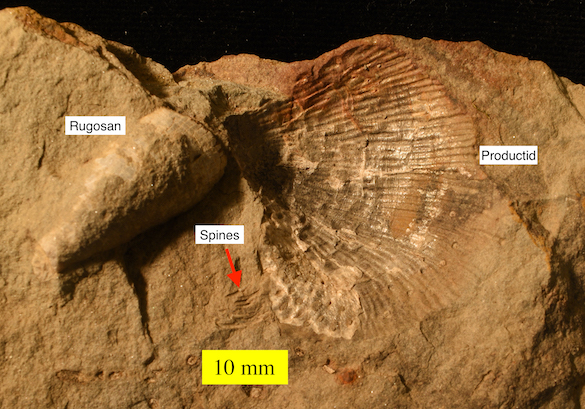

Even though the process of forming a carbonate hardground is geochemical, they are most often recognized by biological phenomena that show they were hard marine seafloors with associated hard substrate-dwelling organisms (sclerobionts). These sclerobionts include encrusting organisms (such as bryozoans, crinoids, oysters, barnacles and the like), borings (often made by polychaete worms, clams, snails and sea urchins), and nestlers that lived in cracks, crevices and caverns of these rocks. In the image above you can see two rugose corals that nestled in shallow concavities on the hardground surface. (It is a closer view of the Ordovician hardground pictured at the top.)

Even though the process of forming a carbonate hardground is geochemical, they are most often recognized by biological phenomena that show they were hard marine seafloors with associated hard substrate-dwelling organisms (sclerobionts). These sclerobionts include encrusting organisms (such as bryozoans, crinoids, oysters, barnacles and the like), borings (often made by polychaete worms, clams, snails and sea urchins), and nestlers that lived in cracks, crevices and caverns of these rocks. In the image above you can see two rugose corals that nestled in shallow concavities on the hardground surface. (It is a closer view of the Ordovician hardground pictured at the top.)

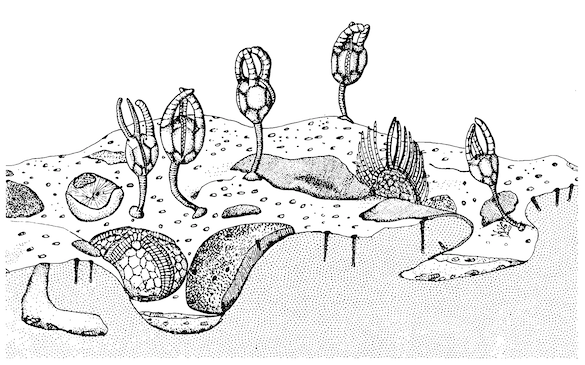

Brett and Liddell (1978, fig. 9, p. 344) constructed this beautiful diagram reconstructing a Middle Ordovician hardground found in southern Ontario, Canada. It shows encrusting bryozoans, stemmed echinoderms, and cross-sections of borings cut into the rock surface.

Brett and Liddell (1978, fig. 9, p. 344) constructed this beautiful diagram reconstructing a Middle Ordovician hardground found in southern Ontario, Canada. It shows encrusting bryozoans, stemmed echinoderms, and cross-sections of borings cut into the rock surface.

The origin story for Wooster’s hardground collection begins in 1984. My wife Gloria and I were exploring sites in northern Kentucky for an upcoming Wooster paleontology course field trip. We stopped by a muddy exposure in Boone County and I immediately saw the above flat cobble weathered out of the outcrop. It was encrusted with beautiful fossils, and had many cylindrical borings. There were hundreds of similar cobbles scattered about. Most were encrusted and bored on both sides, so I knew there was a paleoecological narrative here.

The origin story for Wooster’s hardground collection begins in 1984. My wife Gloria and I were exploring sites in northern Kentucky for an upcoming Wooster paleontology course field trip. We stopped by a muddy exposure in Boone County and I immediately saw the above flat cobble weathered out of the outcrop. It was encrusted with beautiful fossils, and had many cylindrical borings. There were hundreds of similar cobbles scattered about. Most were encrusted and bored on both sides, so I knew there was a paleoecological narrative here.

Here is a close view of another of these Ordovician cobbles in Kentucky. The fine branching network is the bryozoan Corynotrypa, and the stellate encruster is an edrioasteroid echinoderm (Cystaster stellatus). I was enchanted with this little hard substrate community and wrote a paper about how they show a rare example of ecological succession in the fossil record (Wilson, 1985). I wanted to pursue more research on these sclerobionts (even though that term was yet to be coined!).

Here is a close view of another of these Ordovician cobbles in Kentucky. The fine branching network is the bryozoan Corynotrypa, and the stellate encruster is an edrioasteroid echinoderm (Cystaster stellatus). I was enchanted with this little hard substrate community and wrote a paper about how they show a rare example of ecological succession in the fossil record (Wilson, 1985). I wanted to pursue more research on these sclerobionts (even though that term was yet to be coined!).

Shortly after that Kentucky work, I took my first research leave in 1985 to Oxford University in England. I told my host in the Department of Earth Sciences that I was interested in the paleoecology and evolution of hard substrate communities. He quickly recommended that I meet two young paleontologists. The first was Tim Palmer at Aberystwyth University on the western coast of Wales. I contacted Tim and he generously invited me and my little family to his home. Meeting Tim changed my life. Tim had done pioneering work on carbonate hardground communities in the 1970s, resulting in several classic hardground papers (e.g., Palmer and Fürsich, 1974; Palmer and Palmer, 1977) and the first summary of hardground communities through time (Palmer, 1982). During his North American work, he and his wife Caroline collected an astonishing number of hardground samples from Paleozoic and Mesozoic strata. They deposited this material in the US National Museum in Washington, DC, and in the early 1980s it was transferred to Wooster to form the nucleus of our hardground collection. Tim and I, along with other colleagues and students, have added to that collection ever since.

Shortly after that Kentucky work, I took my first research leave in 1985 to Oxford University in England. I told my host in the Department of Earth Sciences that I was interested in the paleoecology and evolution of hard substrate communities. He quickly recommended that I meet two young paleontologists. The first was Tim Palmer at Aberystwyth University on the western coast of Wales. I contacted Tim and he generously invited me and my little family to his home. Meeting Tim changed my life. Tim had done pioneering work on carbonate hardground communities in the 1970s, resulting in several classic hardground papers (e.g., Palmer and Fürsich, 1974; Palmer and Palmer, 1977) and the first summary of hardground communities through time (Palmer, 1982). During his North American work, he and his wife Caroline collected an astonishing number of hardground samples from Paleozoic and Mesozoic strata. They deposited this material in the US National Museum in Washington, DC, and in the early 1980s it was transferred to Wooster to form the nucleus of our hardground collection. Tim and I, along with other colleagues and students, have added to that collection ever since.

The second English paleontologist I was encouraged to meet in 1985 was Paul Taylor of the Natural History Museum in London. As with Tim Palmer, Paul and I quickly became close colleagues and friends. Paul specializes in bryozoans of all types, as well as other organisms found encrusting and boring hard substrates. In fact, it was Paul and I who invented the term sclerobiont (Taylor and Wilson, 2002 and 2003). Over the decades, Paul also contributed to the Wooster hardground collection, as well as to other suites of sclerobionts on other hard substrates. I can’t say enough about what fantastic friends and colleagues Tim and Paul have been for me, and how much they influenced paleontology at Wooster through their work with many of our students. (And yes, they both seem to have fancied pink shirts for fieldwork!)

The second English paleontologist I was encouraged to meet in 1985 was Paul Taylor of the Natural History Museum in London. As with Tim Palmer, Paul and I quickly became close colleagues and friends. Paul specializes in bryozoans of all types, as well as other organisms found encrusting and boring hard substrates. In fact, it was Paul and I who invented the term sclerobiont (Taylor and Wilson, 2002 and 2003). Over the decades, Paul also contributed to the Wooster hardground collection, as well as to other suites of sclerobionts on other hard substrates. I can’t say enough about what fantastic friends and colleagues Tim and Paul have been for me, and how much they influenced paleontology at Wooster through their work with many of our students. (And yes, they both seem to have fancied pink shirts for fieldwork!)

About 20 years I met the remarkably productive Estonian paleontologist Olev Vinn, currently an Associate Professor of Paleontology at the University of Tartu. We have common interests with hard substrate communities and very quickly began to look at hardground faunas in the Baltic (for examples, see Vinn and Wilson, 2010a and 2010b; Vinn et al., 2015). Samples from these and other Baltic Ordovician hardgrounds have been added to the growing Wooster collections. Olev and I have since done diverse work on sclerobionts, especially borings and tube-dwellers. Lately we’ve been concentrating on symbiotic relationships in hard-substrate faunas. Much of this work has recently included our Estonian colleague Ursula Toom.

About 20 years I met the remarkably productive Estonian paleontologist Olev Vinn, currently an Associate Professor of Paleontology at the University of Tartu. We have common interests with hard substrate communities and very quickly began to look at hardground faunas in the Baltic (for examples, see Vinn and Wilson, 2010a and 2010b; Vinn et al., 2015). Samples from these and other Baltic Ordovician hardgrounds have been added to the growing Wooster collections. Olev and I have since done diverse work on sclerobionts, especially borings and tube-dwellers. Lately we’ve been concentrating on symbiotic relationships in hard-substrate faunas. Much of this work has recently included our Estonian colleague Ursula Toom.

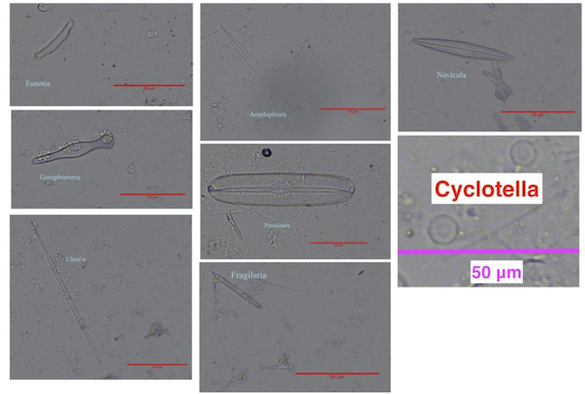

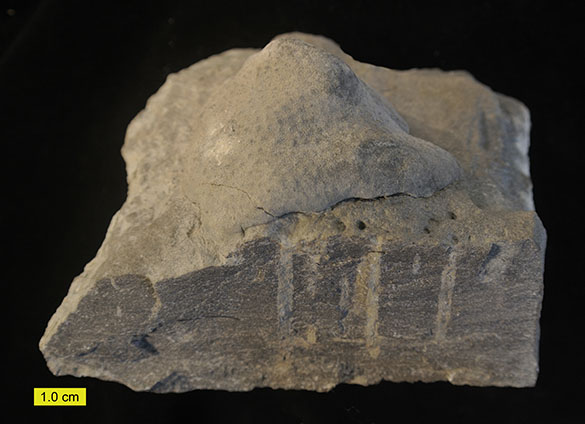

Ordovician (Katian) hardground in cross-section from the Vasalemma quarry in Estonia (GIT 222-499). The borings are the ubiquitous Trypanites. From Figure 9 of Vinn et al. (2015).

Also at the turn of the century I met another English paleontologist: Caroline J. Buttler, currently Head of Collections Development at Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales. (Image from her museum staff profile.) We share a passion for bryozoans, especially big lumpy trepostomes from the Ordovician. She headed a project describing an Upper Ordovician hardground complex from northern Kentucky in which the hardgrounds were eroded and undermined on the seafloor to form caverns with hardground roofs (see below). Samples of these hardgrounds are in several drawers of Wooster’s hardground collection. The roadside outcrop from which they were collected no longer exists, so these specimens are the only record.

Also at the turn of the century I met another English paleontologist: Caroline J. Buttler, currently Head of Collections Development at Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales. (Image from her museum staff profile.) We share a passion for bryozoans, especially big lumpy trepostomes from the Ordovician. She headed a project describing an Upper Ordovician hardground complex from northern Kentucky in which the hardgrounds were eroded and undermined on the seafloor to form caverns with hardground roofs (see below). Samples of these hardgrounds are in several drawers of Wooster’s hardground collection. The roadside outcrop from which they were collected no longer exists, so these specimens are the only record.

One of the cave-forming hardgrounds from the Upper Ordovician of northern Kentucky described by Buttler and Wilson (2018). The large lump on the surface is a trepostome bryozoan colony. The vertical holes are the boring Trypanites. This looks like a typical bored and encrusted carbonate hardground, but in this image it is upside-down!

One of the cave-forming hardgrounds from the Upper Ordovician of northern Kentucky described by Buttler and Wilson (2018). The large lump on the surface is a trepostome bryozoan colony. The vertical holes are the boring Trypanites. This looks like a typical bored and encrusted carbonate hardground, but in this image it is upside-down!

This is the actual orientation of the Buttler and Wilson (2018) hardground. It is the roof of a small cavern. The bryozoan was attached to the ceiling and hung down into the little cave. The borings were actually excavated upwards into the limestone roof. Pretty cool story.

This is the actual orientation of the Buttler and Wilson (2018) hardground. It is the roof of a small cavern. The bryozoan was attached to the ceiling and hung down into the little cave. The borings were actually excavated upwards into the limestone roof. Pretty cool story.

Many other professional colleagues, amateur collectors, and Wooster students have added to the Wooster carbonate hardground collection, as well as to other fossil hard substrate assemblages. I wish I could name them all!

Here are some highlighted carbonate hardgrounds represented in Wooster’s collections. Above is a hardground from the Upper Ordovician of southeastern Ohio. We can identify it as a hardground by the abundant small holes punched into the surface (which are the common Trypanites borings). What is notable in this specimen are the irregular cavities, including the straight cone at the top. These are molds of aragonitic shells like those of many bivalves, gastropods, and cephalopods. (The conical one is from a straight nautiloid cephalopod.) This specimen represents a critical observation that these aragonite shells dissolved on the seafloor, producing fluids that precipitated calcite crystals in the sediments, forming the hardground that was later bored and encrusted. This process, a feature of Calcite Sea geochemistry, was described by Palmer et al. (1988).

Here are some highlighted carbonate hardgrounds represented in Wooster’s collections. Above is a hardground from the Upper Ordovician of southeastern Ohio. We can identify it as a hardground by the abundant small holes punched into the surface (which are the common Trypanites borings). What is notable in this specimen are the irregular cavities, including the straight cone at the top. These are molds of aragonitic shells like those of many bivalves, gastropods, and cephalopods. (The conical one is from a straight nautiloid cephalopod.) This specimen represents a critical observation that these aragonite shells dissolved on the seafloor, producing fluids that precipitated calcite crystals in the sediments, forming the hardground that was later bored and encrusted. This process, a feature of Calcite Sea geochemistry, was described by Palmer et al. (1988).

This slab shows an Upper Ordovician hardground surface in southwestern Ohio with the ovoid borings of bivalves. These borings were described as Petroxestes by Wilson and Palmer (1988).

This slab shows an Upper Ordovician hardground surface in southwestern Ohio with the ovoid borings of bivalves. These borings were described as Petroxestes by Wilson and Palmer (1988).

This is an encrusted hardground from the Middle Ordovician Kanosh Shale of west-central Utah. Most of these encrusters are eocrinoids, an early echinoderm. This hardground series was described by Wilson et al. (1992).

This is an encrusted hardground from the Middle Ordovician Kanosh Shale of west-central Utah. Most of these encrusters are eocrinoids, an early echinoderm. This hardground series was described by Wilson et al. (1992).

The above hardground sample is also from the Kanosh Shale. The large lump on the left is the encrusting bryozoan Nicholsonella.

The above hardground sample is also from the Kanosh Shale. The large lump on the left is the encrusting bryozoan Nicholsonella.

This hardground is from the Carmel Formation (Middle Jurassic) of southwestern Utah. The light-gray layer above the ruler shows numerous bivalve borings known as Gastrochaenolites. It was described and interpreted by Wilson and Palmer (1994) and Wilson (1998). The Carmel Formation has been a popular topic for Wooster Independent Study students over the past 30 years. Search for it in this blog!

This hardground is from the Carmel Formation (Middle Jurassic) of southwestern Utah. The light-gray layer above the ruler shows numerous bivalve borings known as Gastrochaenolites. It was described and interpreted by Wilson and Palmer (1994) and Wilson (1998). The Carmel Formation has been a popular topic for Wooster Independent Study students over the past 30 years. Search for it in this blog!

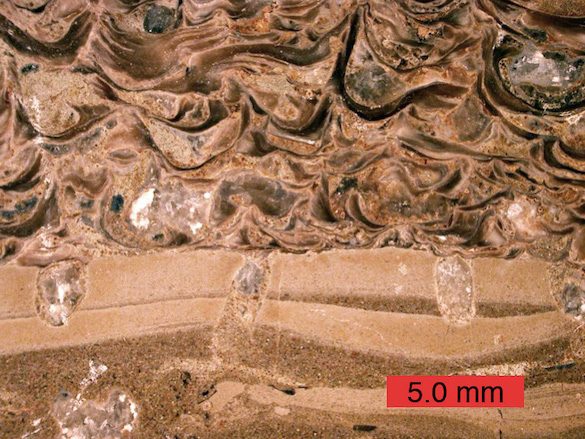

This is a polished cross-section of a Carmel Formation hardground. The layered unit below is the hardground, complete with Gastrochaenolites borings. The top half shows layers of encrusting oysters.

This is a polished cross-section of a Carmel Formation hardground. The layered unit below is the hardground, complete with Gastrochaenolites borings. The top half shows layers of encrusting oysters.

This is a bivalve-bored carbonate hardground in the Ora Formation (Upper Cretaceous, Turonian) near Makhtesh Ramon in the Negev of southern Israel. It makes a very distinctive marker horizon in the Cretaceous of this region.

This is a bivalve-bored carbonate hardground in the Ora Formation (Upper Cretaceous, Turonian) near Makhtesh Ramon in the Negev of southern Israel. It makes a very distinctive marker horizon in the Cretaceous of this region.

I want to end this tour of the Wooster Carbonate Hardground Collection with a specimen that is not technically a carbonate hardground, but interpreted by its common features with hardgrounds. This is a “rockground”, which is an informal term for a sedimentary hard substrate that was encrusted and bioeroded as a rock surface, not a cemented seafloor. This is a wave-eroded coral surface from the Pleistocene exposed on the coast of San Salvador Island, The Bahamas. The small holes are borings formed by clionaid sponges and given the name Entobia. A scleractinian coral encrusts the surface at the upper right. This eroded surface records sea-level changes during the Last Interglacial highstand (White et al., 1998; Wilson et al., 1998; Thompson et al., 2011). You can read the story in this earlier blog post. It was a project that took the lessons of studying carbonate hardgrounds into a bit of paleoclimatology research.

I want to end this tour of the Wooster Carbonate Hardground Collection with a specimen that is not technically a carbonate hardground, but interpreted by its common features with hardgrounds. This is a “rockground”, which is an informal term for a sedimentary hard substrate that was encrusted and bioeroded as a rock surface, not a cemented seafloor. This is a wave-eroded coral surface from the Pleistocene exposed on the coast of San Salvador Island, The Bahamas. The small holes are borings formed by clionaid sponges and given the name Entobia. A scleractinian coral encrusts the surface at the upper right. This eroded surface records sea-level changes during the Last Interglacial highstand (White et al., 1998; Wilson et al., 1998; Thompson et al., 2011). You can read the story in this earlier blog post. It was a project that took the lessons of studying carbonate hardgrounds into a bit of paleoclimatology research.

This is thus a description of the Wooster Carbonate Hardground Collection, which because of its diverse history is unique in the world. If you are ever on the second floor of Scovel Hall, take a peek in the cabinets to see these wonderful rocks and fossils. They have been at the center of my geological and paleontological research program, and thus also for generations of Wooster Independent Study students.

References:

Brett, C.E. and Liddell, W.D., 1978. Preservation and paleoecology of a Middle Ordovician hardground community. Paleobiology 4: 329-348.

Buttler, C.J. and Wilson, M.A. 2018. Paleoecology of an Upper Ordovician submarine cave-dwelling bryozoan fauna and its exposed equivalents in northern Kentucky, USA. Journal of Paleontology 92: 568 – 576.

Erhardt, A.M., Alexandra V. Turchyn, A.V., Dickson, J.A.D., Sadekov, A.Y., Taylor, P.D., Wilson, M.A. and Schrag, D.P. 2020. Chemical composition of carbonate hardground cements as reconstructive tools for Phanerozoic pore fluids. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 21(3): e2019GC008448 (https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GC008448).

Palmer, T.J., 1982. Cambrian to Cretaceous changes in hardground communities. Lethaia 15: 309-323.

Palmer, T.J., and Fürsich, F.T., 1974. The ecology of a Middle Jurassic hardground and crevice fauna. Palaeontology 17: 507-524.

Palmer, T.J., Hudson, J.D., and Wilson, M.A., 1988. Palaeoecological evidence for early aragonite dissolution in ancient calcite seas. Nature 335: 809-810.

Palmer, T.J., and Palmer, C.D., 1977. Faunal distribution and colonization strategy in a Middle Ordovician hardground community. Lethaia 10: 179-199.

Taylor, P.D. and Wilson, M.A. 2002. A new terminology for marine organisms inhabiting hard substrates. Palaios 17: 522-525.

Taylor, P.D. and Wilson, M.A. 2003. Palaeoecology and evolution of marine hard substrate communities. Earth-Science Reviews 62: 1-103.

Thompson, W.G., Curran, H.A., Wilson, M.A. and White, B. 2011. Sea-level oscillations during the Last Interglacial highstand recorded by Bahamas corals. Nature Geoscience 4: 684–687.

Vinn, O. and Wilson, M.A. 2010a. Microconchid-dominated hardground association from the late Pridoli (Silurian) of Saaremaa, Estonia. Palaeontologia Electronica 13(2):9A, 12 p.

Vinn, O. and Wilson, M.A. 2010b. Early large borings from a hardground of Floian-Dapingian age (Early and Middle Ordovician) in northeastern Estonia (Baltica). Carnets de Géologie / Notebooks on Geology, Brest, Note brève / Letter 2010/04 (CG2010_L04).

Vinn, O., Wilson, M.A. and Toom, U. 2015. Bioerosion of inorganic hard substrates in the Ordovician of Estonia (Baltica). PLoS ONE 10(7): e0134279. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134279.

White, B.H., Curran, H.A. and Wilson, M.A. 1998. Bahamian coral reefs yield evidence of a brief sea-level lowstand during the last interglacial. Carbonates and Evaporites 13: 10-22.

Wilson, M.A. 1985. Disturbance and ecologic succession in an Upper Ordovician cobble-dwelling hardground fauna. Science 228: 575-577.

Wilson, M.A., 1998. Succession in a Jurassic marine cavity community and the evolution of cryptic marine faunas. Geology 26, 379-381.

Wilson, M.A., Curran, H.A. and White, B. 1998. Paleontological evidence of a brief global sea-level event during the last interglacial. Lethaia 31: 241-250.

Wilson, M.A., and Palmer, T.J. 1988. Nomenclature of a bivalve boring from the Upper Ordovician of the midwestern United States. Journal of Paleontology. 62: 306–308.

Wilson, M.A. and Palmer, T.J. 1992. Hardgrounds and Hardground Faunas. University of Wales, Aberystwyth, Institute of Earth Studies Publications 9: 1-131.

Wilson, M.A. and Palmer, T.J., 1994. A carbonate hardground in the Carmel Formation (Middle Jurassic, SW Utah, USA) and its associated encrusters, borers and nestlers. Ichnos 3, 79-87.

Wilson, M.A., Palmer, T.J., Guensburg, T.E., Finton, C.D., and Kaufman, L.E. 1992. The development of an Early Ordovician hardground community in response to rapid sea-floor calcite precipitation. Lethaia 25, 19-34.