Guest Blogger: Addison Thompson (’20, Pitzer College) writes about our first 3 days of field work.

6.23.17 For the Utah group, the first day in the field was daunting yet rewarding as our intrepid group of young geologists made themselves acquainted with the Ice Springs Volcanic Field. The Ice Springs Volcanic Field, located in the Black Rock Desert of Utah, is home to many old cinder cone volcanos that currently lay dormant. In the past the cinder cones were active volcanos, spitting and oozing lava. The lava flows have since cooled and currently take the form of basaltic rocks spilling out from four primary cinder cones, Miter, Crescent, Pocket and Terrace.

The day began at 7:15am with breakfast, after which foods were divided for lunch, sandwiches were assembled, and packs were equipped and made field ready. Everything was ready, as was the team and off the Utah group went to the field site, arriving just after 9am. After days of anticipation, stepping out of the car face to face with what the group had read so many articles and papers about was magical. In no time, the group was on their way, climbing up the service road, and eventually up the cinder cone named Miter in order to get a lay of the rocky land.

Team Utah atop the Mitre cinder cone

The terrain comprised uneven, sharp, basaltic rocks and was difficult to traverse, but the group managed. After climbing Miter, the next move was to follow the presumed Miter lava flow path which eventually emptied into a flat basin, an area interpreted to be where a lava flow once pooled. A good section of pahoehoe, a ropy formation of a basaltic rock, was quickly identified, and its sample was taken.

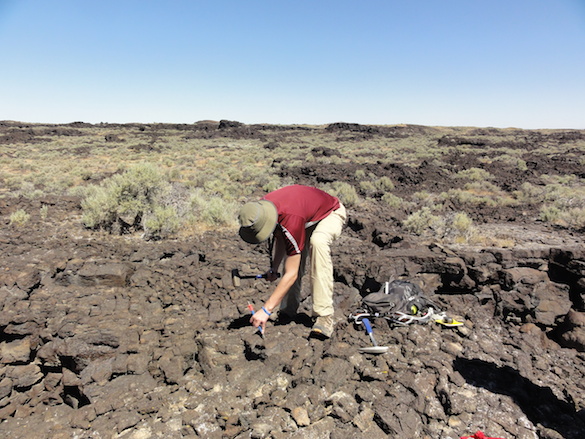

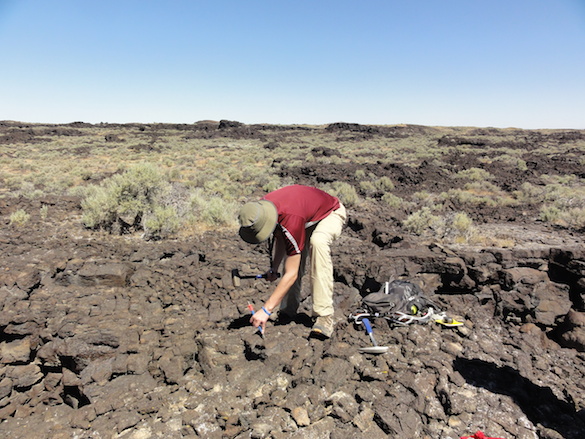

Sam Patzkowsky (’20 Franklin and Marshall College and Team Keck member) dislodging a piece of Pahoehoe to be used as a sample.

With the success of the pahoehoe find, it was time for lunch. Shade was hard to come by, so people did their to take refuge from the incessant beating of the sun. Water was a must. After lunch the group split up in the attempt to identify the Mitre/Crescent lava flow boundary, not an easy task. Regardless of the difficulty, progress was made and we ended the day with promising evidence that could work towards our hypothesis. After a long first day in the field, morale was high but energy was very low; dinner was a welcomed sight.

6.24.17 Waking up on the second day was a breeze. The group had a plan in mind and very little was left to chance. First on the chopping block was a visit to the Carbon-14 dating site followed by accessing the area that is believed to house the Miter/Crescent boundary. Sadly the Carbon-14 dating site was only accessible by a private road, so that idea was nixed. Next up was entering the lava flows from the north west side via a rarely traveled dirt access road. The going was bumpy but eventually the car made it to a suitable stopping point. The walk to the toes (the extent) of the lava flows was a brief flat jog that took minutes; however, the real challenge began when it became necessary to climb the lava flows in order to press on. Over the course of the trip, the sharp basaltic rocks have claimed many a causality, so the group favored precision over speed. In searching for Miter/Crescent boundary evidence, it was impossible to ignore other important geologic occurrences. One of these interesting being a large boulder, about 8ft. tall, comprised of lava bombs that must have been part of a cinder cone that rode a lava flow to the edge.

Measuring a boulder that was transported to its current location by a lava flow.

This helped give an idea about the power of the flows. Measurements of the boulder were taken along with photos for reference.

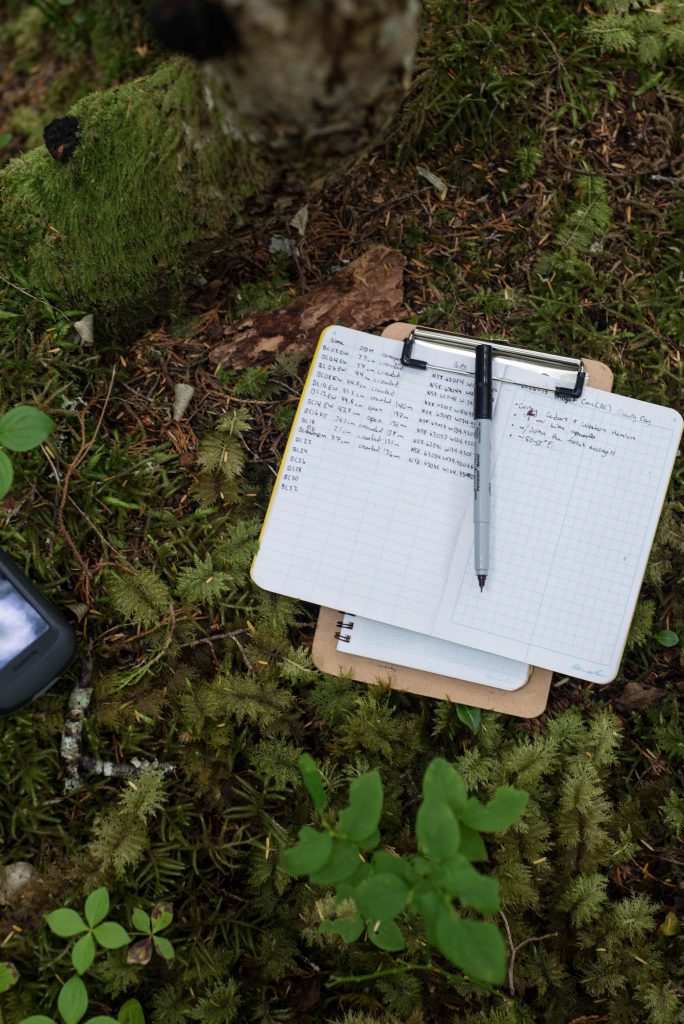

As the group pressed deeper into the flows they began to notice an accumulation of large basaltic slabs sticking out of the ground in all directions and angles. Dr. Pollock noted that information about these slabs could be important towards our ultimate goal, so slab measurements needed to be taken, twenty in all. Taking a slab measurement consisted of noting the coordinates of the hunk of rock, its width in centimeters, taking photos of the slab under examination, and lastly noting the size of the vesicles (holes created by the expulsion of gas during the cooling process).

Two members of Team Keck measuring a slab’s width.

The reward was lunch and maybe shade. Luckily, shade was easier to find than the day before and the group crouched, laid, and sprawled under the angled rocks. But like all good things, lunch came to an end. Regardless of the heat, the group was always eager for more field work so they decided to push farther east in search of a boundary that had previously been visible from a birds eye map. At the boundary, samples were to be taken for geochemistry analysis. Eventually the boundary was reached and the samples were taken. After a efficient day in the field it was time to turn around. Dinner was burgers and everyone went to sleep soon there after.

6.25.17 The third full day in Utah did an excellent of of testing everyones nerves. A special thanks goes out to Dr. Pollock for her cool disposition in the face of a turbulent situation. The day began as a normal day does with breakfast, then lunch packing, and finally going over the mission of the day. The catch was that the back right tire of the car that didn’t want to go along with the plan. Minutes away from the field site the low tire pressure sign flashed on the dashboard so the group turned around and went to go get air for the noticeably deflated tier. However the issue was that the tire had a puncture, not that it simply had low pressure. With the spare now on the car, there was no backup and driving over rocky terrain without a spare tire is a disaster waiting to happen, so the call was made to switch rental cars. This required Dr. Pollock driving the rental up to the Salt Lake Airport to exchange cars, a two hour trip both ways. This exchange took a majority of the day so there was sadly no time left for field work. This was definitely a disappointment, but the group handled it well. The day was instead spent relaxing, uploading information from the field and doing any other minor housekeeping chores. Emily Randall (’20 College of Wooster and Team Keck member) created a map locating every coordinate where a sample had been taken. Finally towards the end of the day a few members went on a hike along an ATV path that wound towards the mountains behind the camp site.

A panoramic taken from the hike.

Although no field work was conducted it was a productive day.