About three years ago I became curious as to who the “Parkinson” was of Parkinson’s Disease. I found the Wikipedia entry for the man, and its first sentence is: “James Parkinson FGS (11 April 1755 – 21 December 1824) was an English surgeon, apothecary, geologist, palaeontologist, and political activist.”

About three years ago I became curious as to who the “Parkinson” was of Parkinson’s Disease. I found the Wikipedia entry for the man, and its first sentence is: “James Parkinson FGS (11 April 1755 – 21 December 1824) was an English surgeon, apothecary, geologist, palaeontologist, and political activist.”

Wait. What? Palaeontologist? The man who described in detail “the shaking palsy” (Parkinson, 1817) so well that the disease was later named for him was also a paleontologist? Why did I not know this? I looked him up in a few handy histories of paleontology and found nothing until I dug deep into the historical literature. I asked my paleontologist friends if they knew Parkinson was one of ours — no one had a clue. There must be a story here.

Of course, many science historians do know about Parkinson’s career in paleontology, and some have described it in detail. One of the best and most readable accounts is by Cherry Lewis (2017). For some reason, though, Parkinson the Paleontologist has slipped out of sight for several generations of his disciplinary community. Why?

I approached my good friends and colleagues Bill Ausich (Ohio State University) and Caroline Buttler (National Museum of Wales) and we teamed up to address Parkinson’s paleontological contributions. Because Bill is one of the world’s top experts on fossil crinoids, and crinoids were a favorite of Parkinson, we started with this group of echinoderms. Just this week our first paper appeared in the journal Earth Sciences History (Ausich et al., 2025). This is a granular account of Parkinson and crinoids, so it is a bit esoteric to most readers. For a broader view of Parkinson the Paleontologist, please see this blog entry describing a presentation we gave in 2024. Everything below comes from Ausich et al. (2025).

ABSTRACT

James Parkinson (1755–1824) was a late 18th and early 19th century apothecary surgeon. In addition to medicine, he published on other topics such as radical politics and paleontology. His paleontological monographs were important during the transitional period when fossils came to be regarded as the remains of once living organisms and were disentangled from Biblical explanations of their origins and distribution. Parkinson published on plants, invertebrates, and vertebrate fossils. Although his work on crinoids was regarded as significant during the 19th century, it has largely been forgotten in the 21st century. Parkinson’s observations led him to interpret crinoids as animals, which was reflected in his morphological terminology, and he expanded crinoid classification beyond that based solely on columnals and pluricolumnals. However, Parkinson’s morphological terminology, like that of many 19th century students of crinoids, did not reflect homology; and he did not apply a Linnean crinoid taxonomy. Despite what is now regarded as inadequate morphological terminology and an obsolete classification scheme, James Parkinson’s significant contributions to the study of crinoids should not be forgotten.

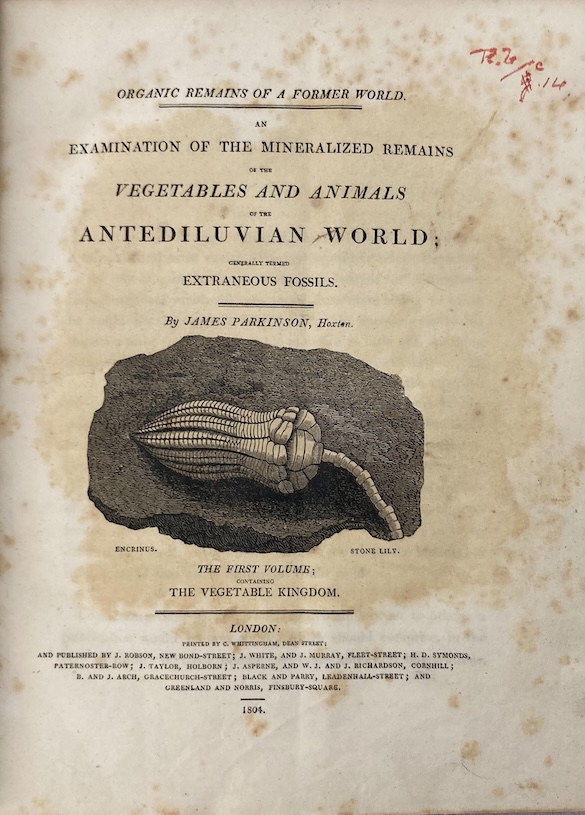

The title page of the first volume of Parkinson’s best known paleontological work: Organic Remains of a Former World (Parkinson, 1804).

The title page of the first volume of Parkinson’s best known paleontological work: Organic Remains of a Former World (Parkinson, 1804).

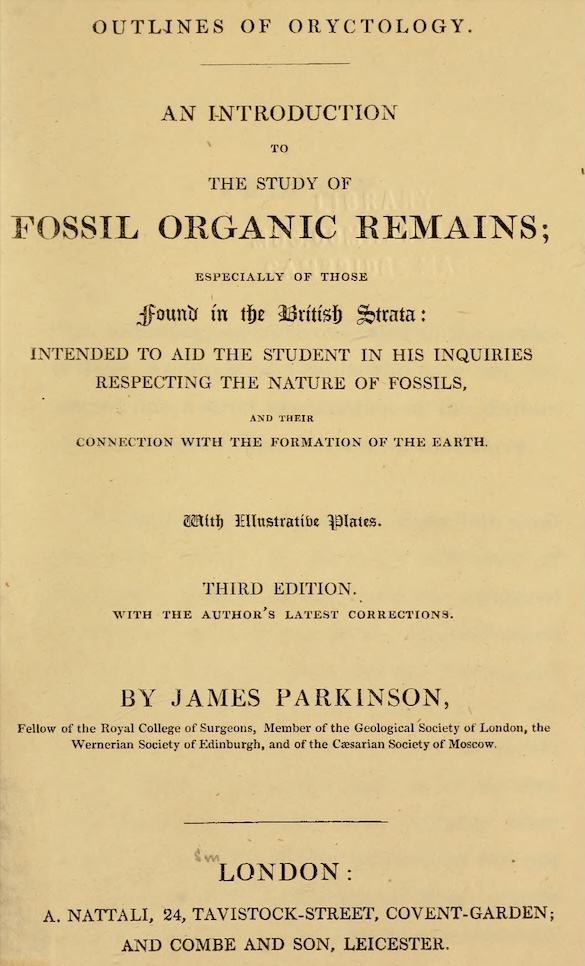

Title page for Outlines of Oryctology. An Introduction to the Study of Fossil Organic Remains (Parkinson, 1821a). Parkinson intended this to be the equivalent of a paleontological textbook for students.

Title page for Outlines of Oryctology. An Introduction to the Study of Fossil Organic Remains (Parkinson, 1821a). Parkinson intended this to be the equivalent of a paleontological textbook for students.

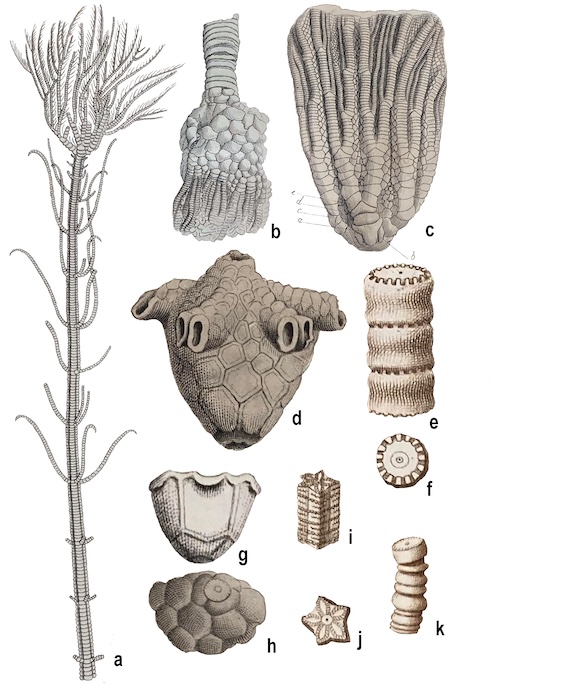

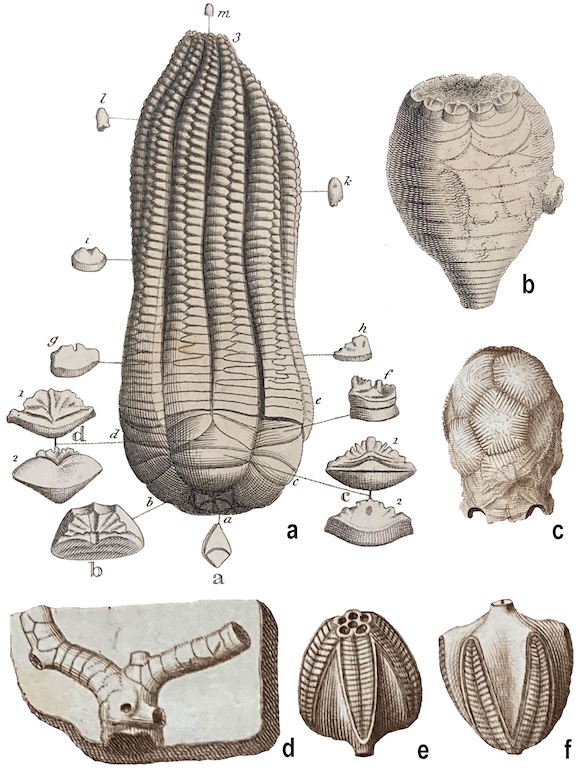

Crinoids illustrated in Parkinson (1808). These plates were remarkably detailed for the time. Note that the crinoid head indicated as b is upside-down.

Crinoids illustrated in Parkinson (1808). These plates were remarkably detailed for the time. Note that the crinoid head indicated as b is upside-down.

Crinoids illustrated in Parkinson (1808), with the exception of e and f, which are related stemmed echinoderms now called blastoids.

Crinoids illustrated in Parkinson (1808), with the exception of e and f, which are related stemmed echinoderms now called blastoids.

For the details of this story, please see the original article: Ausich, Wilson and Buttler (2025).

References: (I’ve listed all of Parkinson’s paleontological writing for the record.)

Ausich, W.I., Wilson, M.A. and Buttler, C.J. 2025. The lost legacy of James Parkinson’s work on the Crinoidea (Echinodermata). Earth Sciences History 44: 421-439.

Lewis, C. 2017. The Enlightened Mr. Parkinson: The Pioneering Life of a Forgotten English Surgeon. Icon Books.

Parkinson, J. 1804. Organic Remains of a Former World. An Examination of the Mineralized Remains of the Vegetables and Animals of the Antediluvian World; Generally Termed Extraneous Fossils. Volume 1. London: C. Whittingham.

Parkinson, J. 1808. Organic Remains of a Former World. An Examination of the Mineralized Remains of the Vegetables and Animals of the Antediluvian World; Generally Termed Extraneous Fossils. Volume 2. London: C. Whittingham.

Parkinson, J. 1811a. Organic Remains of a Former World. An Examination of the Mineralized Remains of the Vegetables and Animals of the Antediluvian World; Generally Termed Extraneous Fossils. Volume 3. London: C. Whittingham.

Parkinson, J. 1811b. XIV. Observations on some of the strata in the neighbourhood of London, and on the fossil remains contained in them. Transactions of the Geological Society of London 1(1): 324‒354.

Parkinson, J. 1817. An Essay on the Shaking Palsy. London: Whittingham and Rowland for Sherwood, Neely and Jones, 66 pp.

Parkinson, J. 1821a. Outlines of Oryctology. An Introduction to the Study of Fossil Organic Remains. London: W. Phillips.

Parkinson, J. 1821b. V. Remarks on the fossils collected by Mr. Phillips near Dover and Folkstone. Transactions of the Geological Society of London 5(1): 52‒59.

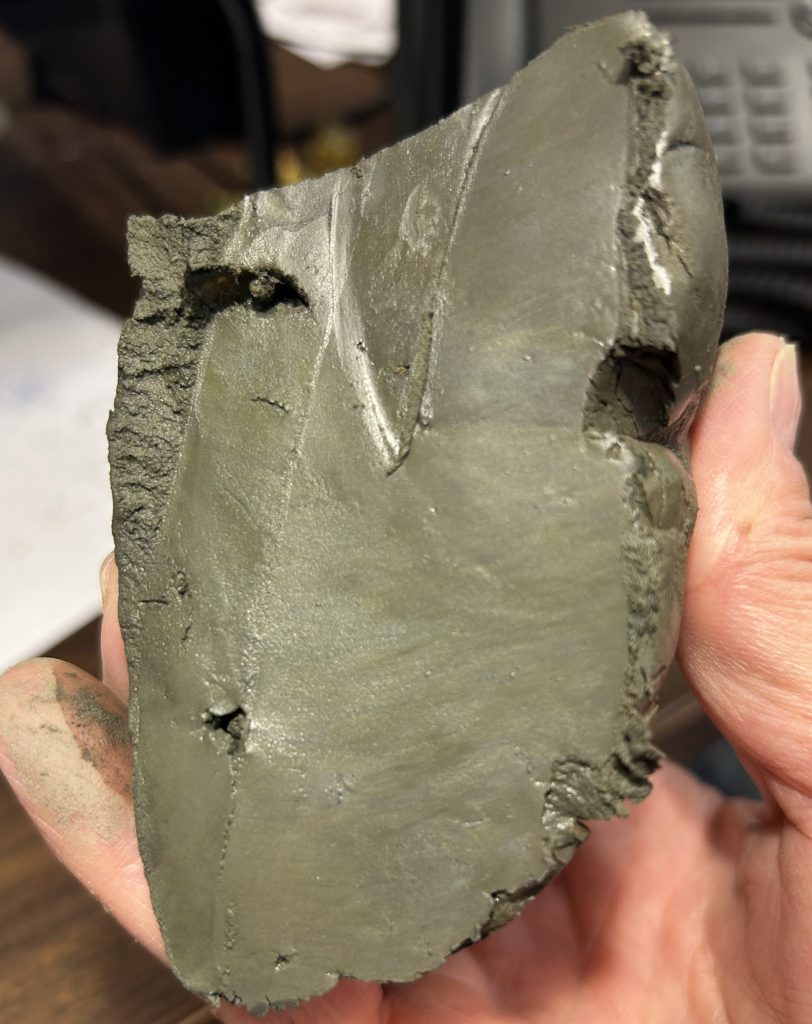

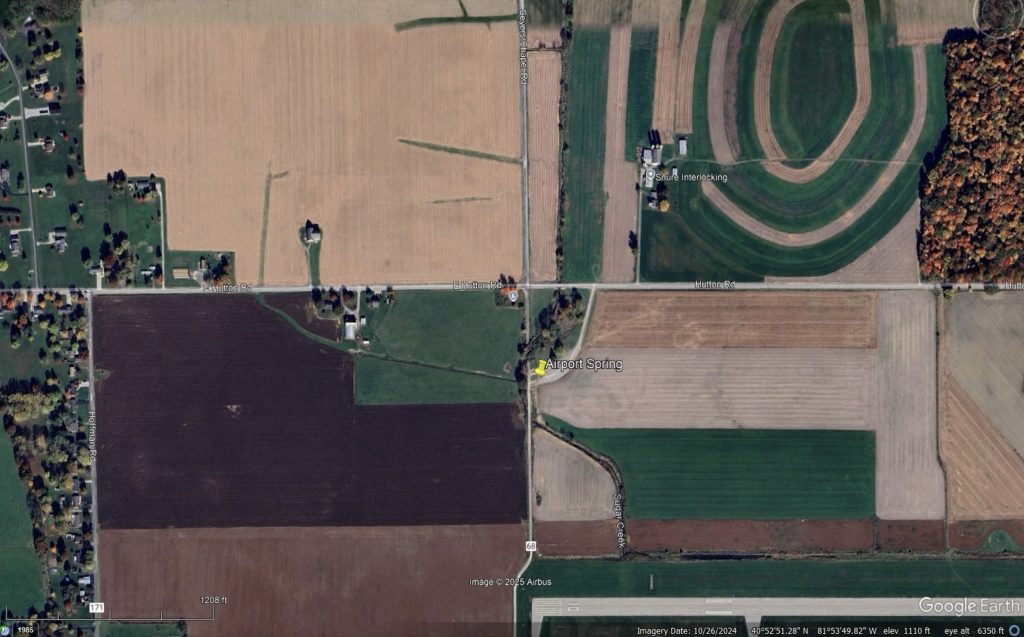

Our primary objective was measuring water levels in the confined Wooster Aquifer, however here we are measuring the water table that is a perched aquifer on top of the clay. Just a kilometer aways is a BTEX plume on top of the clay that is actively being remediated.

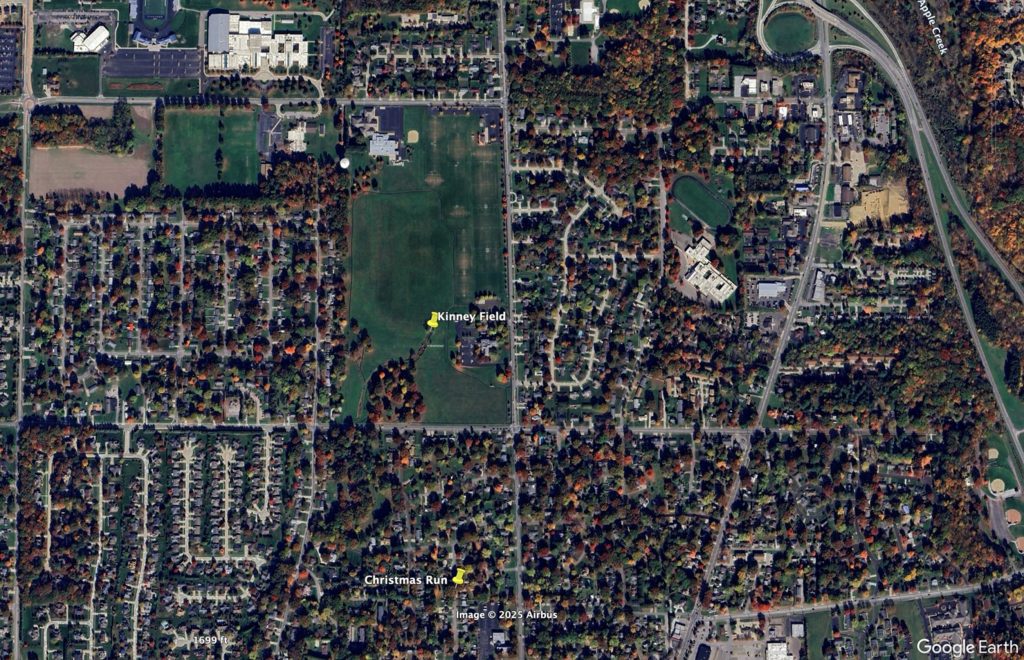

Our primary objective was measuring water levels in the confined Wooster Aquifer, however here we are measuring the water table that is a perched aquifer on top of the clay. Just a kilometer aways is a BTEX plume on top of the clay that is actively being remediated. The observation wells are all completed in the confined Wooster aquifer, and here the team is sneaking up on observation well #4. The levees to Apple Creek are in the background.

The observation wells are all completed in the confined Wooster aquifer, and here the team is sneaking up on observation well #4. The levees to Apple Creek are in the background. We also had a team in the Apple Creek measuring discharge and probing the bottom of the stream for the clay confining layer. What a welcoming team of stream gaugers.

We also had a team in the Apple Creek measuring discharge and probing the bottom of the stream for the clay confining layer. What a welcoming team of stream gaugers. The team bailed a few of the wells to sample the water. We will obtain the stable isotopes of the various waters sampled to investigate the origin of the waters. This was last done by the USGS decades ago.

The team bailed a few of the wells to sample the water. We will obtain the stable isotopes of the various waters sampled to investigate the origin of the waters. This was last done by the USGS decades ago.

One last shot of the Auger team under a big Wooster sky with their feet firmly planted in a recently harvested no-till soybean field with the water treatment plant and its anaerobic digested in the far background.

One last shot of the Auger team under a big Wooster sky with their feet firmly planted in a recently harvested no-till soybean field with the water treatment plant and its anaerobic digested in the far background.

Figure 5. One of three tanks that hold chemical solutions that are added to the water to purify it; this tank holds sodium hypochlorite.

Figure 5. One of three tanks that hold chemical solutions that are added to the water to purify it; this tank holds sodium hypochlorite.

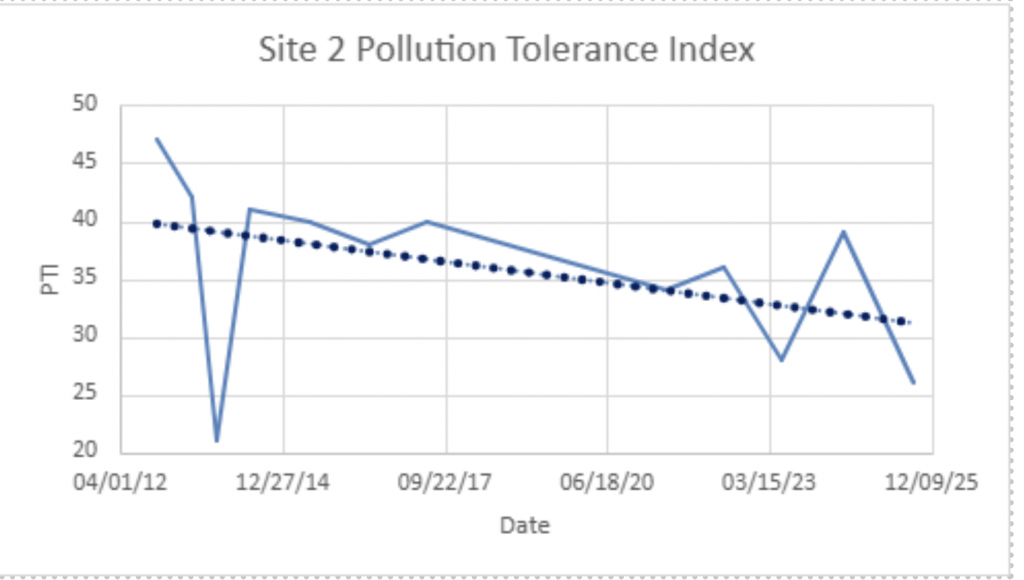

Guest bloggers: Phillipp Drappatz and Elliot Miller, the Hydrology class at the College of Wooster performed a macroinvertebrate survey on 8/25/25 on Apple Creek in Wooster. The first lab of the semester was a trip to Grosjean Park in Wooster. The class was joined by and guided by macroinvertebrate expert Carry Elvie from the CFAES who is also the director of the Bug Zoo. Apple Creek unusually for Ohio is a freestone trout stream under the stewardship of the Clear Fork River chapter of Trout Unlimited, which has been performing surveys since 2012. The purpose of this fieldtrip was to add on the current Trout Unlimited record and to gain insight into the health of the stream based on the assemblage of macroinvertebrates.

Guest bloggers: Phillipp Drappatz and Elliot Miller, the Hydrology class at the College of Wooster performed a macroinvertebrate survey on 8/25/25 on Apple Creek in Wooster. The first lab of the semester was a trip to Grosjean Park in Wooster. The class was joined by and guided by macroinvertebrate expert Carry Elvie from the CFAES who is also the director of the Bug Zoo. Apple Creek unusually for Ohio is a freestone trout stream under the stewardship of the Clear Fork River chapter of Trout Unlimited, which has been performing surveys since 2012. The purpose of this fieldtrip was to add on the current Trout Unlimited record and to gain insight into the health of the stream based on the assemblage of macroinvertebrates.