Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.– As a retirement gift in 2024, my thoughtful department and other friends gave Gloria and me a certificate to stay in a beautiful and charming bed & breakfast establishment in Gettysburg. (Shout out to the Brafferton Inn!) They knew we would enjoy the old town as we explored the local history. The focus of our trip, of course, would be the beautiful and tragic Gettysburg battlefield of the Civil War.

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.– As a retirement gift in 2024, my thoughtful department and other friends gave Gloria and me a certificate to stay in a beautiful and charming bed & breakfast establishment in Gettysburg. (Shout out to the Brafferton Inn!) They knew we would enjoy the old town as we explored the local history. The focus of our trip, of course, would be the beautiful and tragic Gettysburg battlefield of the Civil War.

This month we were finally able to travel to Gettysburg from our new home in northern Virginia. (Yes, it was ironic that this descendant of Union soldiers arrived in a car with Virginia plates!). It was the day after Labor Day when we arrived. The weather was perfect, and there were no crowds anywhere (except, of course, the inescapable Beltway around Washington, DC.) I had been to the battlefield several times before, with one visit recorded in a blog post. This time we could focus on particular parts of the battlefield that interested us. One of those places was Little Round Top, which was on the far left of the Union line on the second day of the battle. We wanted to see for ourselves how the geology of the battlefield influenced the fighting.

On July 2, 1863, the Confederate forces to the west of the Union lines were attacking at several places. The Union officer Brigadier General Gouverneur K. Warren was horrified to discover in the late afternoon that the high ground to the south of the main Union army was virtually undefended and about to be taken by Confederate forces. If the Confederates gained this high ground, which later became known as Little Round Top, they would flank the entire Union line and threaten to “roll it up” to the north. Warren immediately sent for Union troops to occupy and defend Little Round Top. This is why there is a statue of him on the summit looking west (image above). The action on and around Little Round Top was dramatic and bloody, with Union forces retaining the high ground in the face of repeated Confederate attacks up the western slopes. Here is a good account of the fighting.

There have been many excellent descriptions and analyses of the geological influences on the Battle of Gettysburg. Two very useful sources are Smith and Keen (2004) and Cuffey et al. (2006) in the references below. The crucial tactical high grounds on the battlefield are sills and dikes of the coarse-grained mafic intrusive igneous rock diabase. (Some guides call this rock “granite” at Gettysburg. It is not.) The geologic name here is the York Haven Diabase. It is a Jurassic unit that was intruded into the Triassic sedimentary rock sequence called the Gettysburg Formation. These rocks were formed as the modern Atlantic Basin began to pull apart. The softer Gettysburg rocks erode faster than the hard diabase, so over time the sills and dikes begin to appear on the land surface as positive features — the ridge and hills.

There have been many excellent descriptions and analyses of the geological influences on the Battle of Gettysburg. Two very useful sources are Smith and Keen (2004) and Cuffey et al. (2006) in the references below. The crucial tactical high grounds on the battlefield are sills and dikes of the coarse-grained mafic intrusive igneous rock diabase. (Some guides call this rock “granite” at Gettysburg. It is not.) The geologic name here is the York Haven Diabase. It is a Jurassic unit that was intruded into the Triassic sedimentary rock sequence called the Gettysburg Formation. These rocks were formed as the modern Atlantic Basin began to pull apart. The softer Gettysburg rocks erode faster than the hard diabase, so over time the sills and dikes begin to appear on the land surface as positive features — the ridge and hills.

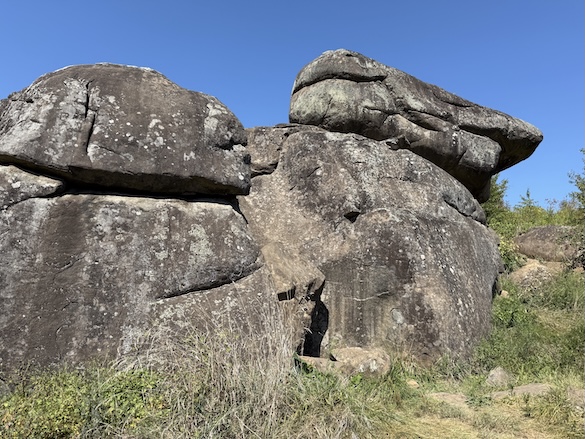

On this trip I was impressed by the numbers and sizes of diabase boulders scattered across Little Round Top and the valley to the west. These were critical in the fighting as both obstacles to coordinated troop movements and safe spaces for soldiers under fire on both sides.

As with the example above, these boulders are rounded, sometime almost spherical. This is curious at first because rounded boulders are often found in rushing rivers that roll the rocks downstream, knocking off corners and smoothing surfaces. These Gettysburg boulders have clearly not been river-worn — they are mostly in place directly above their source rock.

These Gettysburg boulders are rounded by two primary processed. One is exfoliation. As the sediments on top of the diabase intrusions eroded away, the lithostatic pressure on these units decreased. The rocks began to ever so slowly expand and crack, usually along curved surfaces following the landscape above. The second process is surficial frost-wedging. In the winter water from rain and snow seeps into the cracks in the rocks. When this water freezes it expands in volume, wedging the rocks apart and lengthening the cracks. The result is that the diabase units begin to peel like onions and become progressively rounder with time.

This is a view of Devil’s Den from Little Round Top. It is the best exposure of the York Haven Diabase in the park. There was bitter fighting among these rocks and in the valley in front of them. Confederate snipers used the many crevices for cover as they fired at Union soldiers on Little Round Top.

This is a view of Devil’s Den from Little Round Top. It is the best exposure of the York Haven Diabase in the park. There was bitter fighting among these rocks and in the valley in front of them. Confederate snipers used the many crevices for cover as they fired at Union soldiers on Little Round Top.

These boulders show the smooth rounded surfaces typically formed by exfoliation and frost-wedging. These rocks also show erosion from generations of visitors climbing over them in the years since the battle.

These boulders show the smooth rounded surfaces typically formed by exfoliation and frost-wedging. These rocks also show erosion from generations of visitors climbing over them in the years since the battle.

The top of the Devil’s Den outcrop shows the incipient formation of rounded boulders.

The top of the Devil’s Den outcrop shows the incipient formation of rounded boulders.

This boulder lies between Little Round Top and Devil’s Den.

This boulder lies between Little Round Top and Devil’s Den.

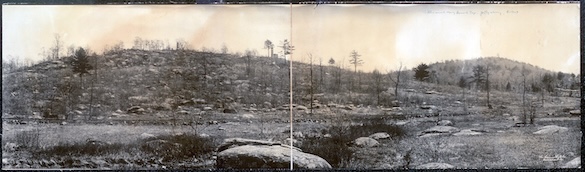

The view of Little Round Top from its western base. This is the slope that the Confederates advanced up as they attacked the Union forces at the crest. It is also the slope that Union troops charged down to win the fight on the evening of July 2, 1863. You can make out the scattering of boulders on this western face.

The view of Little Round Top from its western base. This is the slope that the Confederates advanced up as they attacked the Union forces at the crest. It is also the slope that Union troops charged down to win the fight on the evening of July 2, 1863. You can make out the scattering of boulders on this western face.

The above image shows Little Round Top from the west taken shortly after the battle by the United States Army Corps of Engineers. It shows the boulders well, and the light cover of small trees and bushes. The vegetation here today is reasonably close to that present during the battle.

The above image shows Little Round Top from the west taken shortly after the battle by the United States Army Corps of Engineers. It shows the boulders well, and the light cover of small trees and bushes. The vegetation here today is reasonably close to that present during the battle.

Thank you again to my department and friends for the gift of this trip to Gettysburg. We learned a great deal more about the battle because we had lots of time to explore at our own pace. As with all battlefields there are innumerable stories of tragedy and heroism here. May this park continue to be treasured and protected for the education of future generations.

References —

Cuffey, R.J., Inners, J.D., Fleeger, G.M., Smith, R.C., Neubaum, J.C., Keen, R.C., Butts, L., Delano, H.L., Neubaum, V.A. and Howe, R.H., 2006, Geology of the Gettysburg battlefield: How Mesozoic events and processes impacted American history. In: Pazzaglia, F. J. (Ed.), Excursions in Geology and History: Field Trips in the Middle Atlantic States: Geological Society of America, 8, p.1-16.

Smith, R.C., II, and Keen, R.C., 2004, Regional rifts and the Battle of Gettysburg: Pennsylvania Geology, v. 34, no. 3, p. 2–12.