Today my wife Gloria and I visited the reconstructed Fort Meigs in the northwestern corner of Ohio in Perrysburg, just south of Toledo. It was a beautiful day and we practically had the place to ourselves. It was our first trip since I started my retirement from The College of Wooster. It felt a little naughty to be there during a work day! The above image is of one of the reconstructed fort blockhouses from the outside. Fort Meigs is sited on “Ohio’s War of 1812 battlefield”.

Today my wife Gloria and I visited the reconstructed Fort Meigs in the northwestern corner of Ohio in Perrysburg, just south of Toledo. It was a beautiful day and we practically had the place to ourselves. It was our first trip since I started my retirement from The College of Wooster. It felt a little naughty to be there during a work day! The above image is of one of the reconstructed fort blockhouses from the outside. Fort Meigs is sited on “Ohio’s War of 1812 battlefield”.

This inside view of another blockhouse shows the basic construction of the fort — blockhouses with cannon and rifle gunports connected by a strong wooden palisade. The fort is reconstructed as it would have appeared in 1813

This inside view of another blockhouse shows the basic construction of the fort — blockhouses with cannon and rifle gunports connected by a strong wooden palisade. The fort is reconstructed as it would have appeared in 1813

This reconstruction gun position overlooks the Maumee River, which is very difficult to see through all the vegetation.

This reconstruction gun position overlooks the Maumee River, which is very difficult to see through all the vegetation.

Fort Meigs was constructed by American troops during the bitter winter of 1813. It was designed to be a supply depot for military operations north into Canada and Michigan, as well as for protection of Ohio from invasion by British and Native American forces to the north. General William Henry Harrison was the American commander. The British commander was General Henry Procter, and the Indian warriors were under Chief Tecumseh. On April 28, 1813, the British and Indians began a siege of Fort Meigs, and a significant and bloody battle was fought outside the walls on May 5th. The Americans held the fort during that siege and a second siege attempt in July 1813. The British and Indians retreated and ended the last invasion threat to Ohio.

Fort Meigs was constructed by American troops during the bitter winter of 1813. It was designed to be a supply depot for military operations north into Canada and Michigan, as well as for protection of Ohio from invasion by British and Native American forces to the north. General William Henry Harrison was the American commander. The British commander was General Henry Procter, and the Indian warriors were under Chief Tecumseh. On April 28, 1813, the British and Indians began a siege of Fort Meigs, and a significant and bloody battle was fought outside the walls on May 5th. The Americans held the fort during that siege and a second siege attempt in July 1813. The British and Indians retreated and ended the last invasion threat to Ohio.

This post is not to describe in detail the battles at Fort Meigs, but to discuss the geological reasons Fort Meigs was built in this particular place.

This map shows the geography, towns and forts in the Detroit region during the War of 1812. Fort Meigs is shown in the southwest corner of the map on the Maumee River. The river is key to this story. It was a major transportation artery from Lake Erie into northern Indiana. The Maumee River watershed was otherwise difficult to traverse because of the Great Black Swamp, now entirely drained.

This map shows the geography, towns and forts in the Detroit region during the War of 1812. Fort Meigs is shown in the southwest corner of the map on the Maumee River. The river is key to this story. It was a major transportation artery from Lake Erie into northern Indiana. The Maumee River watershed was otherwise difficult to traverse because of the Great Black Swamp, now entirely drained.

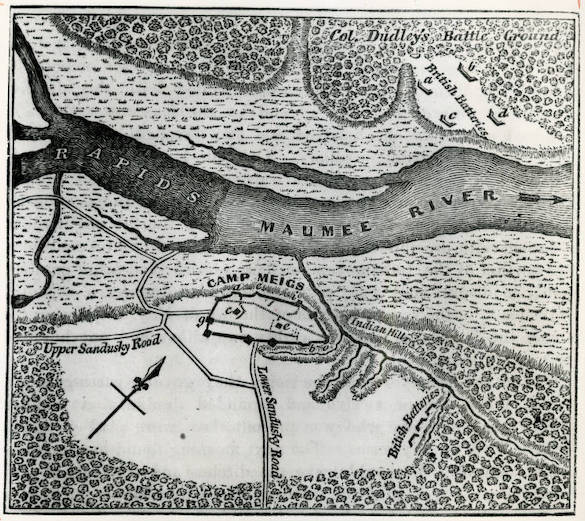

Here in this 1813 map we see the position of Fort Meigs overlooking the Maumee River. The British siege batteries of April and May 1813 are shown to the north and east of the fort. Note that the river flows to the northeast. Critically, just upstream from the fort are “Rapids”. Boats traveling upriver must unload and portage around these rapids. Fort Meigs is situated at this critical point where anyone continuing upriver is subject to cannon and gunfire.

Here in this 1813 map we see the position of Fort Meigs overlooking the Maumee River. The British siege batteries of April and May 1813 are shown to the north and east of the fort. Note that the river flows to the northeast. Critically, just upstream from the fort are “Rapids”. Boats traveling upriver must unload and portage around these rapids. Fort Meigs is situated at this critical point where anyone continuing upriver is subject to cannon and gunfire.

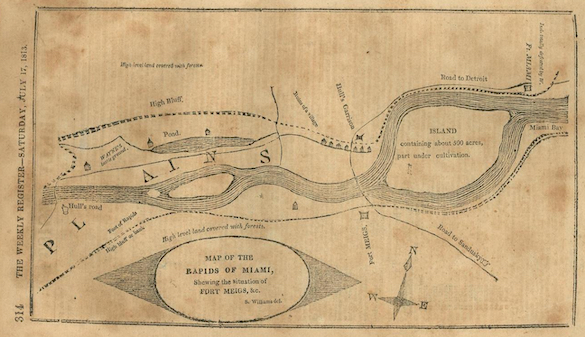

This is another 1813 map of the Fort Meigs area. The Maumee River was sometimes called the “Miami”, which is confusing in Ohio because there is another Miami river.

This is another 1813 map of the Fort Meigs area. The Maumee River was sometimes called the “Miami”, which is confusing in Ohio because there is another Miami river.

Today Fort Meigs still overlooks the Maumee River, bit of course the topography and hydrology here has been highly engineered since 1813. The rapids still exist, though, upstream from the fort and are not visible because of high water levels at the time of this Google Earth image.

Today Fort Meigs still overlooks the Maumee River, bit of course the topography and hydrology here has been highly engineered since 1813. The rapids still exist, though, upstream from the fort and are not visible because of high water levels at the time of this Google Earth image.

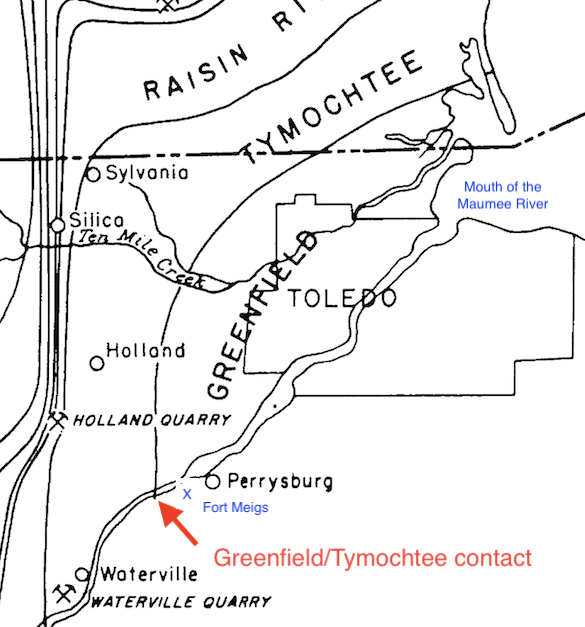

So why do rapids appear at this interval of the Maumee River? Here’s where the geology comes in. In the above map from Ehlers et al. (1951), we see a contact between two geological units at the downstream boundary of the rapids. The red arrow indicates where the river flows off the Tymochtee Dolomite onto the underlying Greenfield Formation. Both of these are Silurian carbonate units. Critically, the Tymochtee Dolomite is more resistant than the upper beds of the Greenfield Formation. The riverbed on the Tymochtee is therefore more rocky, thus producing the rapids. Fort Meigs, at the small blue “x” on the map, took advantage of this change in the navigability of the river. Geology controlled this War of 1812 battlefield.

So why do rapids appear at this interval of the Maumee River? Here’s where the geology comes in. In the above map from Ehlers et al. (1951), we see a contact between two geological units at the downstream boundary of the rapids. The red arrow indicates where the river flows off the Tymochtee Dolomite onto the underlying Greenfield Formation. Both of these are Silurian carbonate units. Critically, the Tymochtee Dolomite is more resistant than the upper beds of the Greenfield Formation. The riverbed on the Tymochtee is therefore more rocky, thus producing the rapids. Fort Meigs, at the small blue “x” on the map, took advantage of this change in the navigability of the river. Geology controlled this War of 1812 battlefield.

We didn’t go down to the rapids today, so I got the above image of the rapids from Google Maps. Slabs of the Tymochtee Dolomite are visible in the riverbed and banks. A much more evocative image of these carbonate rocks can be seen here. I learned a new word for a biome through this research: alvar. These flooded, flat carbonate exposures support a unique flora and fauna that is periodically wet and dry. The rapids here are part of the Maumee River alvar.

We didn’t go down to the rapids today, so I got the above image of the rapids from Google Maps. Slabs of the Tymochtee Dolomite are visible in the riverbed and banks. A much more evocative image of these carbonate rocks can be seen here. I learned a new word for a biome through this research: alvar. These flooded, flat carbonate exposures support a unique flora and fauna that is periodically wet and dry. The rapids here are part of the Maumee River alvar.

Reference:

Ehlers, G.M., Stumm, E.C. and Kesling, R.V. 1951. Devonian rocks of southeastern Michigan and northwestern Ohio. Stratigraphic field trip of the Geological Society of America, Detroit Meeting (November 1951)