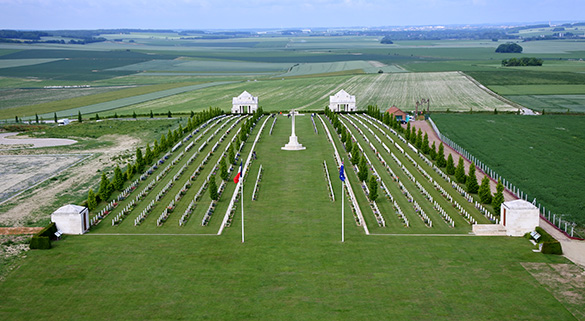

Amiens, France — I had two days between the bryozoan meeting in Vienna and the fieldwork in southwestern France, so I decided to visit the World War I battlefields in the Somme Valley of northern France. It was a somber experience of natural beauty, stark and effective memorial architecture, and one of the deepest historical tragedies. I had a similar journey in 2010 to my Grandfather Snuffer’s World War I battlefield in the Meuse-Argonne. Above is a view of the cemetery at the Australian National Memorial near Villers-Bretonneux.

Amiens, France — I had two days between the bryozoan meeting in Vienna and the fieldwork in southwestern France, so I decided to visit the World War I battlefields in the Somme Valley of northern France. It was a somber experience of natural beauty, stark and effective memorial architecture, and one of the deepest historical tragedies. I had a similar journey in 2010 to my Grandfather Snuffer’s World War I battlefield in the Meuse-Argonne. Above is a view of the cemetery at the Australian National Memorial near Villers-Bretonneux.

There were two major battles between the Allies and the Germans in the Somme Valley. The first, between July 1 and November 18, 1916, was the largest in terms of soldiers involved and lost. There were more than a million casualties, about even on each side, during those four and a half months of battle. A large proportion of those losses occurred on the first day; indeed, the first few minutes. The results were a draw. The second Battle of the Somme took place August 21 through September 2, 1918, and was an overwhelming Allied victory. This brief blog post is about my impressions of the battlefields a century later, so please follow the links for the historical background.

Gravestones at the Australian National Memorial. These are primarily for Australian soldiers, but there were also stones for New Zealanders, South Africans, Britons, and Canadians.

Gravestones at the Australian National Memorial. These are primarily for Australian soldiers, but there were also stones for New Zealanders, South Africans, Britons, and Canadians.

Flanders poppies grow naturally in this region, and they are also used decoratively in cemeteries. See the famous poem by John McCrae: In Flanders Fields.

Flanders poppies grow naturally in this region, and they are also used decoratively in cemeteries. See the famous poem by John McCrae: In Flanders Fields.

An emblem of the soldier’s unit is engraved at the top of each stone.

An emblem of the soldier’s unit is engraved at the top of each stone.

The memorial building has walls of Portland Limestone (Jurassic of southern England) listing the thousands of missing Australian soldiers in the first battle.

The memorial building has walls of Portland Limestone (Jurassic of southern England) listing the thousands of missing Australian soldiers in the first battle.

In a compounding irony, the Australian National Memorial buildings and gravestones were shot up in turn during a skirmish here between Allied soldiers and invading Germans in 1940.

In a compounding irony, the Australian National Memorial buildings and gravestones were shot up in turn during a skirmish here between Allied soldiers and invading Germans in 1940.

This is the small Proyart German Cemetery from the 1918 battle. There are over 450 cemeteries from all the involved nationalities throughout the valley. This one is seldom visited but immaculately maintained. The town of Proyart saw much fighting from the beginning of the war to its end.

This is the small Proyart German Cemetery from the 1918 battle. There are over 450 cemeteries from all the involved nationalities throughout the valley. This one is seldom visited but immaculately maintained. The town of Proyart saw much fighting from the beginning of the war to its end.

An unknown German soldier. There are tens of thousands of unknown graves on the battlefields, matched by long, long lists of the missing.

An unknown German soldier. There are tens of thousands of unknown graves on the battlefields, matched by long, long lists of the missing.

Lochnagar Crater is a massive hole produced by the explosion of a British mine under the German lines on July 1, 1916 — the first day of the first battle. The bedrock is Cretaceous chalk, which was easy to tunnel with simple tools except that it had to be done in silence. No pickaxes were allowed. The last part of the explosives tunnel was dug under the German trenches with bayonettes alone. It is said that one soldier would pry a flint from the wall as another caught it before it struck the floor. The mine explosion was at that time the largest man-made sound in history.

Lochnagar Crater is a massive hole produced by the explosion of a British mine under the German lines on July 1, 1916 — the first day of the first battle. The bedrock is Cretaceous chalk, which was easy to tunnel with simple tools except that it had to be done in silence. No pickaxes were allowed. The last part of the explosives tunnel was dug under the German trenches with bayonettes alone. It is said that one soldier would pry a flint from the wall as another caught it before it struck the floor. The mine explosion was at that time the largest man-made sound in history.

You’ve heard that French farmers still find live artillery shells in their fields? Here’s one of them. About 60 tons a year of WWI explosives are removed from the Somme battlefields. The one above was marked for disposal with a red plastic cup. Demolition teams drive through the countryside in armored ammunition disposal vehicles removing munitions.

You’ve heard that French farmers still find live artillery shells in their fields? Here’s one of them. About 60 tons a year of WWI explosives are removed from the Somme battlefields. The one above was marked for disposal with a red plastic cup. Demolition teams drive through the countryside in armored ammunition disposal vehicles removing munitions.

The local farmers repurpose many WWI items. Here a modern barbed wire fence is constructed with German barbed wire stakes from the war.

The local farmers repurpose many WWI items. Here a modern barbed wire fence is constructed with German barbed wire stakes from the war.

The Battle of Thiepval Ridge was a complicated and bloody operation in September, 1916. The ridge which cost so many Allied lives was selected as the site of the Anglo-French Memorial to the Missing of the Somme. Over 72,000 names are engraved on the limestone panels. The architectural design itself is moving. Its high arches reflect the missing space in lives after so many personal tragedies without even grave for compensation.

The Battle of Thiepval Ridge was a complicated and bloody operation in September, 1916. The ridge which cost so many Allied lives was selected as the site of the Anglo-French Memorial to the Missing of the Somme. Over 72,000 names are engraved on the limestone panels. The architectural design itself is moving. Its high arches reflect the missing space in lives after so many personal tragedies without even grave for compensation.

A departure from the grim narrative with a brief paleontological note: The Jurassic crinoid Apiocrinites can be identified in the steps of the memorial. I know it well from other contexts.

A departure from the grim narrative with a brief paleontological note: The Jurassic crinoid Apiocrinites can be identified in the steps of the memorial. I know it well from other contexts.

There is a very well maintained part of the 1916 battlefield at Beaumont-Hamel. Here the Newfoundland Regiment attacked the German lines on the first day of the first Battle of the Somme. The regiment was destroyed in less than twenty minutes after they emerged from their trenches. Six-hundred and seventy men were casualties.

There is a very well maintained part of the 1916 battlefield at Beaumont-Hamel. Here the Newfoundland Regiment attacked the German lines on the first day of the first Battle of the Somme. The regiment was destroyed in less than twenty minutes after they emerged from their trenches. Six-hundred and seventy men were casualties.

These are remnants of the first line of British trenches.

These are remnants of the first line of British trenches.

The killing field of the Newfoundlanders. It is estimated 300-400 of their bodies still remain in the churned soil.

The killing field of the Newfoundlanders. It is estimated 300-400 of their bodies still remain in the churned soil.

There was an original blasted trunk here called the Danger Tree. It is midway between the British and German lines, about as far as the Newfoundlanders got on July 1, 1916.

There was an original blasted trunk here called the Danger Tree. It is midway between the British and German lines, about as far as the Newfoundlanders got on July 1, 1916.

A caribou memorial faces the old German positions from the trenches of the Newfoundlanders. All the stones below it are from Newfoundland. The site is maintained by the government of Canada.

A caribou memorial faces the old German positions from the trenches of the Newfoundlanders. All the stones below it are from Newfoundland. The site is maintained by the government of Canada.

The end of my journey was to Hawthorn Ridge, site of a German position blown up by another British mine on the first day of the 1916 battle. The explosion was filmed.

The end of my journey was to Hawthorn Ridge, site of a German position blown up by another British mine on the first day of the 1916 battle. The explosion was filmed.

This is the same perspective as the famous photographs and films of the 1916 Hawthorn Ridge explosion. The trees are growing on the crater rim.

This is the same perspective as the famous photographs and films of the 1916 Hawthorn Ridge explosion. The trees are growing on the crater rim.

This is a famous photo of British soldiers awaiting the Hawthorn mine explosion on July 1, 1916. They had tunneled out of a trench into a sunken lane in no-man’s-land to get as close to the German lines as possible for their attack.

This is a famous photo of British soldiers awaiting the Hawthorn mine explosion on July 1, 1916. They had tunneled out of a trench into a sunken lane in no-man’s-land to get as close to the German lines as possible for their attack.

That sunken lane is still present 101 years later.

That sunken lane is still present 101 years later.

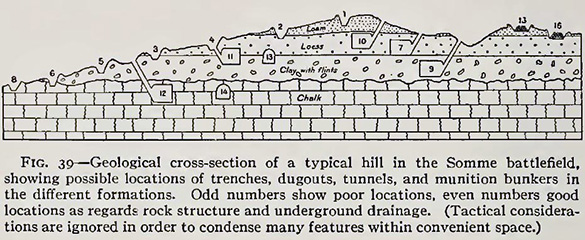

I wanted to add more about the geology of the battlefield, but the human tragedy is so overwhelming I decided to leave it for later. For now, see the geological cross-section below. Also consider the remarkable observation that the intensity of the artillery bombardments actually changed the geology of the region. “Bombturbation” is a term that has been proposed in our clinical scientific way.