Wooster, OH – The summer portion of the Keck Iceland project is officially over, but our research isn’t finished. We’ll be working together throughout the academic year and will synthesize our final results at the Keck Symposium at Wesleyan University in April 2017. Along the way, we’ll be presenting at GSA in Denver, Colorado. We wrote and submitted 4(!) abstracts based on our work this summer. Here they are:

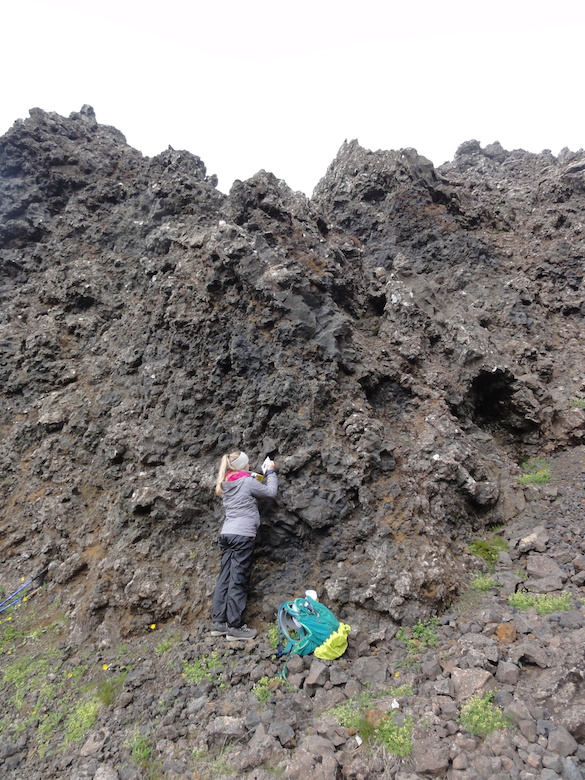

Cara Lembo (’17, Amherst) stands next to a ridge-parallel dike intruding through a tephra cone. Helgafell, a hyalocastite edifice, is in the distance.

NEW INSIGHTS ON THE FORMATION OF GLACIOVOLCANIC TINDAR RIDGES FROM DETAILED MAPPING OF UNDIRHLIDAR RIDGE, SW ICELAND

HEINEMAN, Rachel1, LEMBO, Cara2, ENGEN, Carl-Lars3, KOCHTITZKY, William4, WALLACE, Chloe5, ORDEN, Michelle4, THOMPSON, Anna C6, KUMPF, Benjamin5, EDWARDS, Benjamin R.4 and POLLOCK, Meagen5, (1)Department of Geology, Oberlin College, 52 West Lorain St, Oberlin, OH 44074, (2)Department of Geology, Amherst College, 11 Barrett Hill Dr, Amherst, MA 01002, (3)Department of Geology, Beloit College, 700 College Street, Box 777, Beloit, WI 53511, (4)Department of Earth Sciences, Dickinson College, 28 N. College Street, Carlisle, PA 17013, (5)Department of Geology, The College of Wooster, 944 College Mall, Wooster, OH 44691, (6)Department of Geology, Carleton College, One North College Street, Northfield, MN 55057, rheinema@oberlin.edu

Undirhlíðar ridge on the Reykjanes Peninsula in southwest Iceland is a glaciovolcanic tindar formed by fissure eruptions under ice. Previous work in two quarries along the ridge shows that this specific tindar has had a complex eruption history. Here we report new results from investigations along the length of the ridge (~3 km) between the quarries. We have identified aerially significant fragmental deposits and a potential vent area on the ridge’s eastern side. The newly mapped tephra deposits are dominated by lapilli- and ash-size grains that are palagonitized to some degree (~20-60%) but locally contain up to ~75% fresh glass. Basal units are tuff breccia to volcanic breccia with basaltic and rare gabbroic lithic clasts. Upper units are finely bedded with few large clasts and some glassy bombs. Locally, lapilli-tuff units show repetitive normally graded bedding and cross bedding. Measured bedding attitudes suggest that present exposures represent a moderately eroded tephra cone that was subsequently intruded by basaltic dikes. Extending north and south of the tephra cone, the upper surface of the ridge comprises pillow rubble with outcrops of massive basalts showing radial jointing and concentric vesicle patterns. All of the outcrops appear to be similar coarse-grained, olivine- and plagioclase-bearing basalts; ongoing petrographic and geochemical analysis will determine if the bodies represent “megapillows” or if they are related to intrusions that are present in both quarries. Along the western side of the ridge, lapilli tuff and/or volcaniclastic diamictites overlie pillow lava (or volcanic breccia made of pillow fragments) that is locally intruded by dikes. In northern gullies, at least two stratigraphically distinct units of pillow lava are present. In order to communicate the implications of our detailed research to a broad audience, we are constructing two “map tours” of the ridge: one that is centered on the abandoned and accessible Undirhlíðar quarry, and another that describes features along the upper part of the ridge between the quarries. Stops along the tour include exposures of dikes, pillow lavas, and erosional alcoves within the tephra cone. The goal of these tours is to compare similar units across the ridge and quarry and to show the general anatomy of a glaciovolcanic ridge.

Rachel Heineman (’17, Oberlin) stands next to a potential “megapillow.”

Cross section of a pillow lava, with Michelle Orden’s (’17, Dickinson) head for scale.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF GLACIOVOLCANIC PILLOW LAVAS FROM UNDIRHLIDAR, SW ICELAND

THOMPSON, Anna C1, ORDEN, Michelle2, LEMBO, Cara3, WALLACE, Chloe4, KUMPF, Benjamin4, HEINEMAN, Rachel5, ENGEN, Carl-Lars6, EDWARDS, Ben2, POLLOCK, Meagen4 and KOCHTITZKY, William2, (1)Department of Geology, Carleton College, One North College Street, Northfield, MN 55057, (2)Department of Earth Sciences, Dickinson College, 28 N. College Street, Carlisle, PA 17013, (3)Department of Geology, Amherst College, 11 Barrett Hill Dr, Amherst, MA 01002, (4)Department of Geology, The College of Wooster, 944 College Mall, Wooster, OH 44691, (5)Department of Geology, Oberlin College, 52 West Lorain St, Oberlin, OH 44074, (6)Department of Geology, Beloit College, 700 College Street, Box 777, Beloit, WI 53511, thompsona@carleton.edu

Chloe Wallace (’17, Wooster) samples glassy pillow lava rinds for geochemical analysis by XRF and FTIR.

GEOCHEMICAL CONSTRAINTS ON THE MAGMATIC SYSTEM AND ERUPTIVE ENVIRONMENT OF A GLACIOVOLCANIC TINDAR RIDGE FROM UNDIRHLíðAR, SW ICELAND

WALLACE, Chloe1, KUMPF, Benjamin1, HEINEMAN, Rachel2, LEMBO, Cara3, ORDEN, Michelle4, THOMPSON, Anna C5, ENGEN, Carl-Lars6, KOCHTITZKY, William4, POLLOCK, Meagen1, EDWARDS, Ben4and HIATT, Alex1, (1)Department of Geology, The College of Wooster, 944 College Mall, Wooster, OH 44691, (2)Department of Geology, Oberlin College, 52 West Lorain St, Oberlin, OH 44074, (3)Department of Geology, Amherst College, 11 Barrett Hill Drive, Amherst, MA 01002, (4)Department of Earth Sciences, Dickinson College, 28 N. College Street, Carlisle, PA 17013, (5)Department of Geology, Carleton College, One North College Street, Northfield, MN 55057, (6)Department of Geology, Beloit College, 700 College Street, Box 777, Beloit, WI 53511, cwallace17@wooster.edu

Glaciovolcanic tindar ridges are landforms created by the eruption of magma through fissure swarms into ice. The cores of many of these ridges comprise basaltic pillow lava, so they serve an accessible analogue for effusive mid-oceanic ridge volcanism. Furthermore, similar landforms have been identified on Mars, and thus they may also serve as models for planetary volcanic eruptions. To better understand pillow formation and effusive glaciovolcanic eruptions, we are investigating Undirhlíðar ridge, a pillow-dominated tindar on the Reykjanes Peninsula in southwest Iceland. Our detailed mapping and sampling in two rock quarries along the ridge and in the ~3 km area between the quarries show that this specific tindar ridge has had a complex eruption history. In the northern quarry (Undirhlíðar), Pollock et al. (2014) demonstrated that at least two geochemically distinct magma batches have erupted. Further trace element and isotope analyses in the southern quarry (Vatnsskarð) suggest that the ridge is fed by a heterogeneous mantle source. Isotopic Pb data show a spatially systematic linear array, which is consistent with a heterogeneous mantle mixing between depleted and enriched endmembers. The occurrence of multiple magma batches in dikes and irregular intrusions suggests that these structures are important to transporting magma within the volcanic edifice. Glassy pillow rinds were sampled for volatile analysis by FTIR in order to determine how paleo-water pressures vary along the ridge. In Undirhlíðar quarry, paleo-water pressures decrease with stratigraphic height (1.6-0.7 MPa). In Vatnsskarð quarry, paleo-water pressures show evidence of two separate eruptions, where pressure values decrease with an increase in stratigraphic height from 1.1 to 0.7 MPa over ~30 m, at which point pressure resets to 1.1 MPa and continues to decrease with elevation. When comparing the two quarries, paleo-water pressures in the upper units of Undirhlíðar and all the units in Vatnsskarð have similar values (0.7-1.1 MPa), and these are lower than the basal units of Undirhlíðar (1.2-1.6 MPa). Overall, compositional variations correlate with stratigraphy and spatial distribution along axis, suggesting that glaciovolcanic eruptions and their resulting landforms show a higher level of complexity than previously thought.

A view looking NE into Undirhlidar quarry on a moody Icelandic day. (Photo Credit: Ben Edwards)

3-D

MAPPING OF QUARRY WALLS TO CONSTRAIN THE INTERNAL STRUCTURE OF A GLACIOVOLCANIC TINDAR, SW ICELAND

EDWARDS, Benjamin R.1, POLLOCK, Meagen2, KOCHTITZKY, William1 and ENGEN, Carl-Lars3, (1)Department of Earth Sciences, Dickinson College, 28 N. College Street, Carlisle, PA 17013, (2)Department of Geology, The College of Wooster, 944 College Mall, Wooster, OH 44691, (3)Department of Geology, Beloit College, 700 College Street, Box 777, Beloit, WI 53511, edwardsb@dickinson.edu

Documentation of the internal structures of volcanoes are critical for understanding how edifices are built over time, especially for glaciovolcanoes, which have rarely formed historically and are inaccessible during eruptions. We have been unraveling the internal structure of a complex glaciovolcanic ridge (tindar) in southwestern Iceland for the past 5 years in order to better understand the sequence of events that built the ridge. Undirhlidar ridge is ~5 km long, and has been dissected by two different aggregate mines along its axis. The northern mine (Undirhlidar quarry) is inactive and has walls up to 40 m in height that fully expose several critical stratigraphic relationships including multiple sequences of separate pillow lava flows, cross-cutting dikes that locally feed overlying pillow flows, and ridge parallel, continuous massive jointed basaltic units that may be the remnants of internal lava supply networks. The second quarry, ~3 km to the southwest (Vatnsskard quarry) is presently active and continually has new exposures. This quarry only penetrates halfway through the width of the ridge but has ~500 m of exposure along strike. It also has remnants of what appears to be the internal magma distributary system, and many components clearly show evidence that they were (and some still are) open lava tubes. While both quarries contain excellent exposures, many of the structures are difficult to safely access or are inaccessible due to mining activity. In order to overcome access issues, we have used Structure-from-Motion techniques to make 3-D maps of the quarry walls. A series of overlapping pictures were taken from points constrained with D-GPS using a Trimble GeoXH data logger and external antennae. The image locations with corrected positions were imported into Photoscan software to create a point cloud representative for each quarry and to derive a Digital Elevation Model with a reported vertical resolution of less than 1 m. Field testing of a preliminary, low resolution DEM shows that measurements of dyke widths on the DEM have errors of ~5% relative to measurements on the ground. Measurements made from the field-generated DEM will provide significantly better constraints on deposit thicknesses and volume estimates compared to traditional methods of estimating unit thicknesses on vertical faces.