Guest bloggers: Andrew Wayrynen and Jeff Gunderson

First attempt at collecting wood in Muir Inlet with Dan Lawson

Two College of Wooster geologists in the Alaskan wilderness is always a recipe for success. Thanks to Dr. Wiles and the geo gang, we took our interests in glaciology and dendroclimatology to Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve in Southern Alaska, where scrambling up glaciers, maneuvering slippery alders, and finally sampling old growth trees became daily routine. As the first time in Alaska for Andrew and the second for Jeff, the beauty of the historic place was stunning and allowed scientific inquiry to flourish in its wake. Jeff’s tall task stood as “bridging the gap” of Glacier Bay’s glacial and climate history and Andrew, an English major by night, explored the location’s history in accordance with the writing of esteemed preservationist John Muir.

We were met by none other than Nick Wiesenberg at the Juneau airport, where we promptly sorted out food supplies and last minute gear checklists. After a few quick stops around town and a quiet night in the state’s capitol we were set to take off for Glacier Bay and to enter the field. We spent the night in a park-designated campsite and the next day we, as a trio, embarked a national park service boat to scoop up Dr. Wiles and his bright-eyed photographer Jesse who were already at Marble Mountain. Thereafter, we voyaged up-Bay to Muir Inlet where we set up camp between the Eastern-Arm’s McBride and Riggs Glaciers.

Carrying supplies in the sand dunes to cross the river and find the log

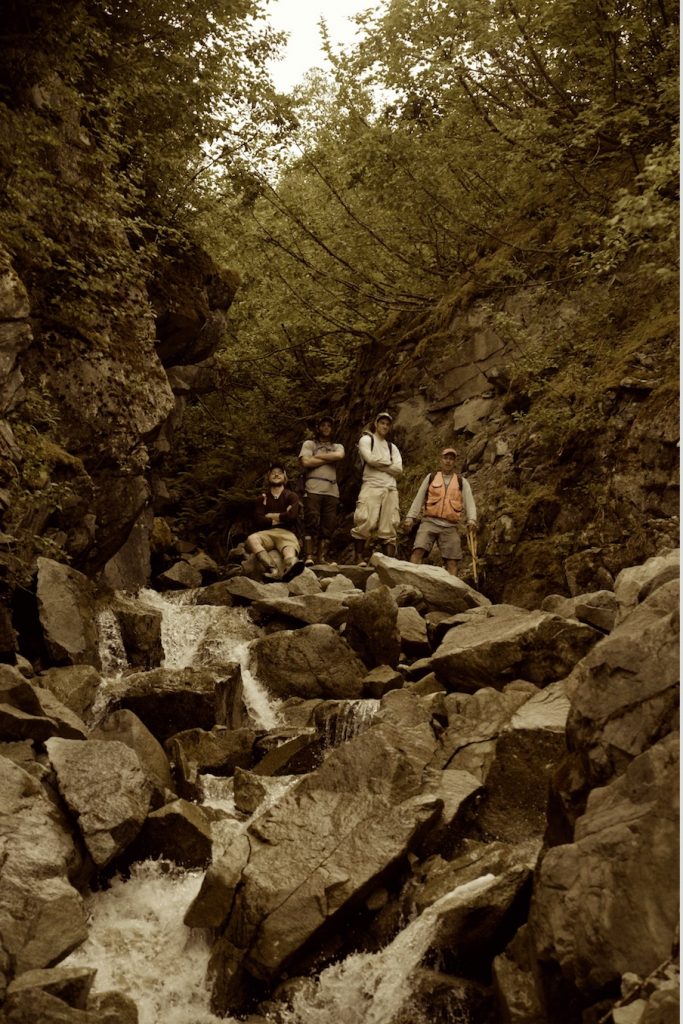

The older generation showing us how it’s done

The following day, the five of us kayaked to Wolf Lake in hopes of finding logs that would bridge the 2000-year old gap in the Glacier Bay tree-ring chronology. This totaled to a 14-mile round trip venture, where 6 miles were by foot and 8 were by kayak. The trek followed a decent sized creek, through marshy, bug-infested alders up a ridge to a drainage divide. From the top, a beautiful lake was visible whose crystal waters contained the remnants of an icy past. Down the other side of the divide was our goal- the roaring braided streams and the encasing alluvial fans. The mosquitoes brandished whatever the hell it is that they so eagerly stab us with and we set forth, mesh bug nets swaying in the wind, serving as a sort of lifeline. At last in the outwash plain, we spread out and surveyed the area for the missing pieces to our chronological puzzle. Our efforts proved fruitful, for there was more wood than we could conceivably carry.

A teachable moment for us in the field

We’re considering making a show called Alaskan Bushwhackers

We’re considering making a show called Alaskan Bushwhackers

This first day of fieldwork truly set the tone for the remainder of the project. Sunny skies would subsequently outweigh threatening thunderous clouds, and complacency would never overcome hard work. The following afternoon the crew seized the opportunity to explore McBride Glacier by sea kayak, both resting tired legs and experiencing the immensity of one of the only remaining tidewater glaciers left in the Bay. We found it incredibly rewarding and inspiring to be so close to the very living beings that we have, and indeed will continue to, spend so much time studying. That afternoon, ice appeared the most brilliant shade of blue. Later that night, rice and beans never tasted so good.

Glaciers make us smile… stay posted for part 2

Excellent writing and images, Team Alaska! Another advantage for desert fieldwork, though: no mosquitoes!

Pingback: Warming at the Third Pole, Northwest Kashmir and Tree Rings | College of Wooster Tree Ring Lab