My retiring Sophomore Research student, Annette Hilton (’17), is excellent at making acetate peels. These peels, like the one above she made from a mysterious Callovian (Middle Jurassic) coral, show fine internal details of calcareous fossils and rocks.

My retiring Sophomore Research student, Annette Hilton (’17), is excellent at making acetate peels. These peels, like the one above she made from a mysterious Callovian (Middle Jurassic) coral, show fine internal details of calcareous fossils and rocks.

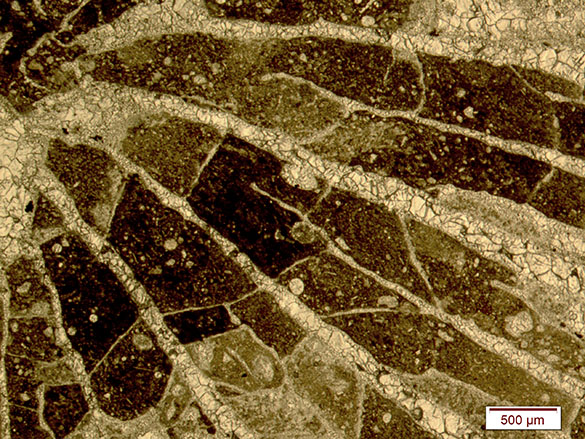

This is a closer view of the acetate peel of the coral showing incredible detail in the radiating septa and connecting dissepiments. This is a solitary coral from the Matmor Formation of southern Israel. We thought we knew what it was until we examined this peel and saw features we can’t match with any coral taxa. (Experts are invited to tell us what it is!) This view looks like it is from a thin-section, but it is all acetate and was made in about 20 minutes.

This is a closer view of the acetate peel of the coral showing incredible detail in the radiating septa and connecting dissepiments. This is a solitary coral from the Matmor Formation of southern Israel. We thought we knew what it was until we examined this peel and saw features we can’t match with any coral taxa. (Experts are invited to tell us what it is!) This view looks like it is from a thin-section, but it is all acetate and was made in about 20 minutes.

An acetate peel is a replica of a polished and etched surface of a carbonate rock or fossil mounted between glass slides for microscopic examination. Peels cannot give the mineralogical and crystallographic information that a thin-section can, but they are faster and easier to make. For most carbonate rocks most of the information you need for a petrographic analysis can be recovered from an acetate peel. In many paleontological applications, an acetate peel is preferred to a thin-section because you get essentially two dimensions without sometimes confusing depth.

To make a peel you need the following:

A trim saw for rock cutting.

A grinding wheel with diamond embedded disks (with 45µm and 30µm plates)

Grinding grit (3.0 µm) in a water slurry on a glass plate.

Acetate paper.

A supply of 5% hydrochloric acid in a small dish.

A supply of water in another small dish.

A squeeze bottle of acetone.

Glass biology slides (one by three inches)

Transparent tape.

Scissors

A carbonate rock or fossil

We’re now going to show you how we make peels. This process was worked out by my friend Tim Palmer and me back in the 1980s. See the reference at the end of this entry.

Annette is in her required safety gear about to start the process by cutting a fossil. She needs to cut a flat surface that is usually perpendicular to bedding in a carbonate rock, or through a fossil at some interesting angle.

Annette is in her required safety gear about to start the process by cutting a fossil. She needs to cut a flat surface that is usually perpendicular to bedding in a carbonate rock, or through a fossil at some interesting angle.

The specimen approaches the spinning diamond-embedded blade of the rock saw. Annette is holding the rock sample steady on a carriage she is pushing towards the blade. It is important to hold the specimen still as the blade cuts through it.

The specimen approaches the spinning diamond-embedded blade of the rock saw. Annette is holding the rock sample steady on a carriage she is pushing towards the blade. It is important to hold the specimen still as the blade cuts through it.

My camera is faster than I thought. Not only do you see those suspended drops of water, the spray is frozen in the air! The cut is almost complete.

My camera is faster than I thought. Not only do you see those suspended drops of water, the spray is frozen in the air! The cut is almost complete.

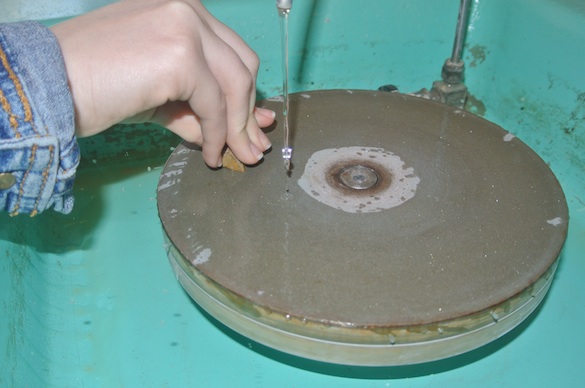

Now we use a diamond-embedded grinding wheel (45 µm or 30 µm) to polish the surface cut with the saw. This will be the side from which we make the acetate peel.

Now we use a diamond-embedded grinding wheel (45 µm or 30 µm) to polish the surface cut with the saw. This will be the side from which we make the acetate peel.

A closer view of the rock (which contains an embedded bryozoan, by the way) being polished flat on the spinning wheel.

A closer view of the rock (which contains an embedded bryozoan, by the way) being polished flat on the spinning wheel.

The best peels are made from surfaces that have the finest polish. We are using a 3.0 µm grit-water slurry on a glass plate to again polish the rock surface as smooth as possible, removing all saw and grinding marks.

The best peels are made from surfaces that have the finest polish. We are using a 3.0 µm grit-water slurry on a glass plate to again polish the rock surface as smooth as possible, removing all saw and grinding marks.

Keep the plate wet and push down hard to polish the cut surface in the grit slurry. With carbonate rocks and fossils it takes no more than five minutes here to get an excellent polish.

Keep the plate wet and push down hard to polish the cut surface in the grit slurry. With carbonate rocks and fossils it takes no more than five minutes here to get an excellent polish.

Wash the specimen thoroughly in water to remove all grit. Check the polished surface for grinding marks. If you see any, return to the glass plate and slurry for more polishing.

Wash the specimen thoroughly in water to remove all grit. Check the polished surface for grinding marks. If you see any, return to the glass plate and slurry for more polishing.

We’re ready for the simple etching process. We use a Petri dish half-filled with 5% hydrochloric acid and a another dish with water. (Yes, I have a dirty hood in my lab.)

We’re ready for the simple etching process. We use a Petri dish half-filled with 5% hydrochloric acid and a another dish with water. (Yes, I have a dirty hood in my lab.)

Annette is suspending the polished surface of the specimen downward into the acid bath. She dips it in only a couple millimeters or so. The acid reacts with the carbonate and fizzes. Her fingers are safely above the action, but if you’re nervous you can use tongs to hold the specimen. We usually keep the specimen in the acid for about 15 seconds, and then quench it with the water in the second dish. The etching time will vary with the strength of the acid and carbonate content of the specimen.

Annette is suspending the polished surface of the specimen downward into the acid bath. She dips it in only a couple millimeters or so. The acid reacts with the carbonate and fizzes. Her fingers are safely above the action, but if you’re nervous you can use tongs to hold the specimen. We usually keep the specimen in the acid for about 15 seconds, and then quench it with the water in the second dish. The etching time will vary with the strength of the acid and carbonate content of the specimen.

This is the kit you need to make the acetate peel itself. Note that we use a thin acetate rather than the thick sheets preferred by others.

This is the kit you need to make the acetate peel itself. Note that we use a thin acetate rather than the thick sheets preferred by others.

The tricky part. When the specimen is dry, cut a piece of acetate somewhat larger than the etched surface. We then hold this acetate and the specimen in one hand, and the squeeze bottle of acetone in the other. The next step is to flood the etched surface, which is held flat and upwards, with the acetone and quickly place the acetate on the wetted surface. The acetate will adhere fast, so smooth it out with your fingers across the etched surface. At this point the acetone is partially dissolving the acetate, causing it to flow into the tiny nooks and crannies of the etched surface. The acetone evaporates and the acetate hardens into this microtopography.

The tricky part. When the specimen is dry, cut a piece of acetate somewhat larger than the etched surface. We then hold this acetate and the specimen in one hand, and the squeeze bottle of acetone in the other. The next step is to flood the etched surface, which is held flat and upwards, with the acetone and quickly place the acetate on the wetted surface. The acetate will adhere fast, so smooth it out with your fingers across the etched surface. At this point the acetone is partially dissolving the acetate, causing it to flow into the tiny nooks and crannies of the etched surface. The acetone evaporates and the acetate hardens into this microtopography.

If you did it correctly, you now have a sheet of acetate adhering entirely to the etched surface. With practice you learn how to avoid bubbles between the acetate and specimen. Opinions vary and how long to let the system thoroughly dry. We found that we can proceed to the next step in about five minutes.

If you did it correctly, you now have a sheet of acetate adhering entirely to the etched surface. With practice you learn how to avoid bubbles between the acetate and specimen. Opinions vary and how long to let the system thoroughly dry. We found that we can proceed to the next step in about five minutes.

Now you peel! Slowly and firmly pull the acetate off the specimen.

Now you peel! Slowly and firmly pull the acetate off the specimen.

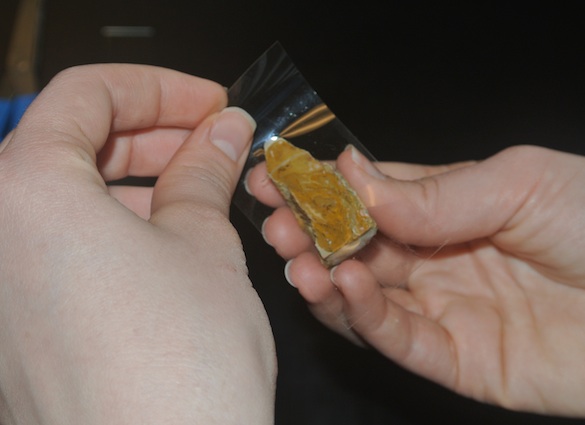

Carefully trim the acetate with scissors. Place this peel between two glass slides, squeeze tight, and seal the assemblage like a sandwich with transparent tape. You have now made an acetate peel. Easy!

Carefully trim the acetate with scissors. Place this peel between two glass slides, squeeze tight, and seal the assemblage like a sandwich with transparent tape. You have now made an acetate peel. Easy!

Here’s our finished product. Twenty minutes from rock saw to peel. You’ll have to wait until another blog post to see what this particular peel shows us!

Here’s our finished product. Twenty minutes from rock saw to peel. You’ll have to wait until another blog post to see what this particular peel shows us!

Reference:

Wilson, M.A. and Palmer, T.J. 1989. Preparation of acetate peels. In: Feldmann, R.M., Chapman, R.E. and Hannibal, J.T. (eds.), Paleotechniques. The Paleontological Society Special Publication 4: 142-145. [The link is to a PDF.]

Pingback: Phylum Mollusca: Introduction (October 6 & 8) | Invertebrate Paleontology at Wooster

Hi there,

I also did this procedure to get information of the texture of some carbonate rocks years ago. Probably more than 200 for a research project. We also classified the rocks and gave a very detailed description of their texture. I found, under my experience, that your explanation of how to make a acetate peel is very excellent and easy to follow. The photographs are a perfect guide and the fact that you put an explanation of this procedure on the internet is more than amazing.

Thanks for sharing this very ‘specific’ information with the rest of the world.

Concepcion

Thank you very much, Concepcion. Good luck with your work! Mark

Excited to use this method to do some analysis soon!

-Juda C.

A Good explanation.

We also used this method in the UK in 1979 both on Carbonate sections and indeed Granite etched using HF (very carefully!) and stained using Alizarin Red and K-Ferricyanide

Hi Mark. Do you know if Grafix clear acetate of 0.005 of thickness works well too?

Hi Daniel: I’ve never tried it. I imagine it would work. The key is to have acetate that is not too thick that it obscures the details, and not too thin that it tears when peeling. Good luck!

Dear Mark:

Thank you for the quick response.

Hi Mark, may I ask how long you can keep the peel between the slides before studying it under the microscope?

Hi Nuy: You can study the peel microscopically immediately. Best wishes, Mark