In my early days of teaching paleontology I had an enthusiastic trading program with colleagues around the country. I would supply fine fossils from the Upper Ordovician of southern Ohio for what I considered exotic specimens from elsewhere. In one of the trades I received a block of limestone from the Road Canyon Formation found in the Glass Mountains of southwestern Texas. It was from the Roadian Stage of the Guadalupian Series of the Permian System, so about 270 million years old.

In my early days of teaching paleontology I had an enthusiastic trading program with colleagues around the country. I would supply fine fossils from the Upper Ordovician of southern Ohio for what I considered exotic specimens from elsewhere. In one of the trades I received a block of limestone from the Road Canyon Formation found in the Glass Mountains of southwestern Texas. It was from the Roadian Stage of the Guadalupian Series of the Permian System, so about 270 million years old.

This limestone is famous for its silicified fossils. The original calcite shells of the fossils were replaced by silica (similar to the mineral quartz), yet the matrix of the limestone remained mostly calcite. This meant that my students and I could immerse the limestone block in hydrochloric acid and watch the calcite matrix dissolve and the silicified shells remain as an insoluble residue. What emerged from the acid were beautiful fossils where even the finest spines are preserved.

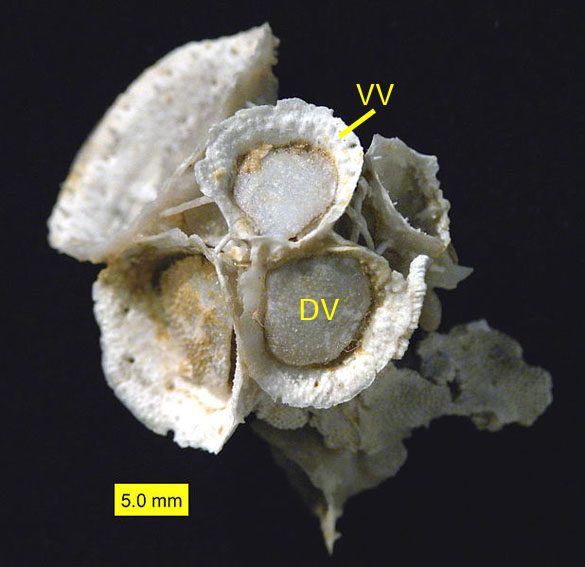

Cluster of Hercosestria cribrosa brachiopods with the conical ventral valve (VV) and lid-like dorsal valve (DV) labelled.

Our particular block was part of a reef complex in which the primary framework was made by conical brachiopods attached to each other by long spines. These brachiopods are unlike any that came before or since. Each shell consists of two valves: the ventral valve is an open cone and the dorsal valve attaches to it as a hinged lid. The spines come from the ventral valve and wrap around other shells to make a wave-resistant structure — a reef. These brachiopod reefs were unique to the Permian.

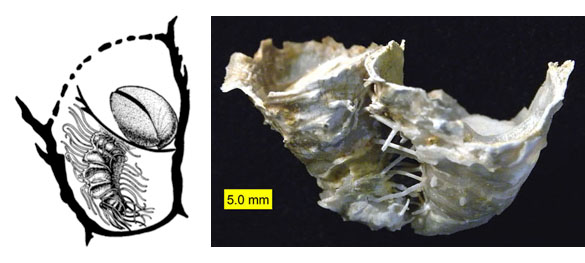

The species we have, Hercosestria cribrosa Cooper & Grant 1969, belongs to the Superfamily Richthofenioidea in the Order Productida, so they are often called richthofenids and productids. Hercosestria had its moment of paleontological fame in the mid-1970s. Two prominent paleontologists, Richard Cowen and Richard Grant, debated the role of models in assessing the functional morphology of extinct species. Richthofenid brachiopods were used as an example: did they flap their dorsal valves to create a current (Cowen’s suggestion), or did they crack the valves open and pump the water in and out with their fleshy lophophores? Grant showed a specimen of Hercosestria cribrosa with another brachiopod living on its dorsal valve, convincingly demonstrating that the valves did not likely flap.

On the left is a figure from Grant (1975) showing Hercosestria cribrosa with a small brachiopod living on its dorsal valve; on the right is a side view of two H. cribrosa ventral valves with attaching spines.

To make it even more interesting, by the 1980s there was considerable support for the idea that richthofenid brachiopods like Hercosestria had algal symbionts in their tissues and thus were effectively photosynthetic!

To see the other Wooster’s Fossil of the Week posts, please click on this link or the appropriate tag to the right.

References —

Cooper, G.A. and Grant, R.E. 1969. New Permian brachiopods from west Texas. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 1: 1-20.

Cowen, R. 1975. ‘Flapping valves’ in brachiopods. Lethaia 8: 23-29.

Cowen, R. 1983, Algal symbiosis and its recognition in the fossil record: in Tevesz, M.J.S. and McCall, P.L., eds., Biotic Interactions in Recent and Fossil Benthic Communities: Plenum Press, New York, p. 431-478.

Grant, R.E. 1975. Methods and conclusions in functional analysis: a reply. Lethaia 8: 31–33.