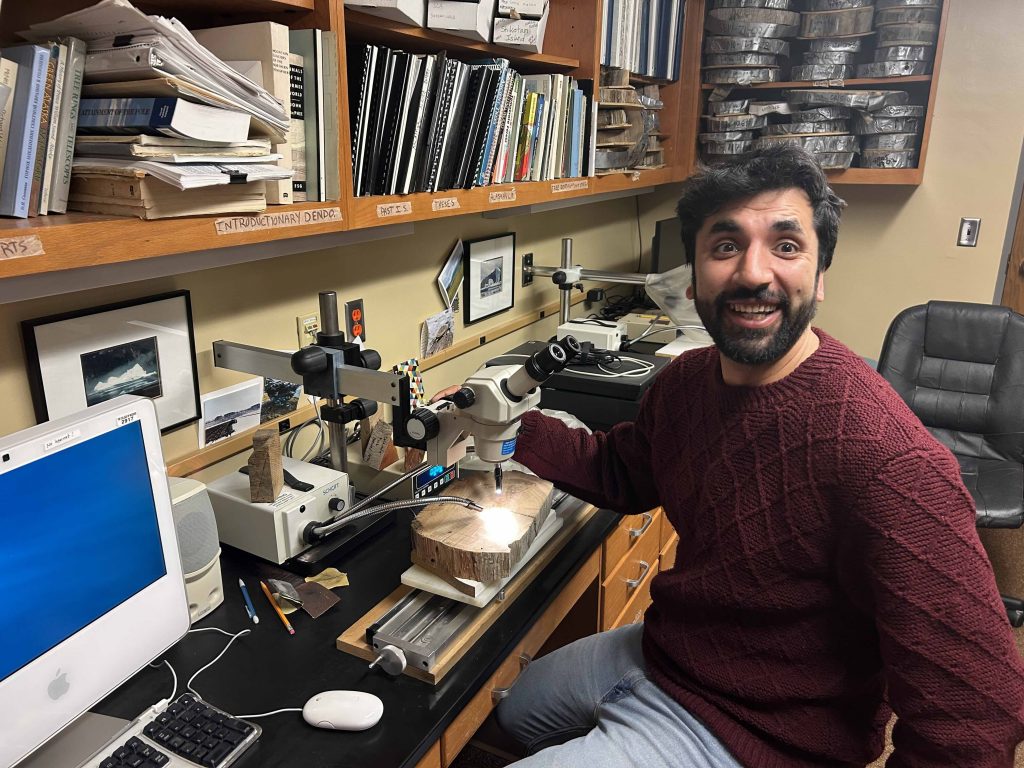

It was a honor to welcome Dr. Nicolás Young (’05) back to the College to be our 44th Osgood Speaker. Dr. Young hails from the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory’s Cosmo Lab, where he is a Associate Research Scientist. Nicolás is a leader in developing the analytical side of cosmogenic surface exposure dating and is a gifted and creative field geologist.

His Osgood talk “Disappearance of North Atlantic ice sheets over the last 2.6 million years” focused on his work with colleagues aimed at trying to figure out what ice sheets may have looked like during past warm intervals in Earth’s recent history, which is particularly important considering Earth’s current climate trajectory. This work is extremely challenging because evidence of small ice sheets has largely been destroyed by repeated episodes of subsequent ice advance. His team has been combining new sampling approaches in the field with evolving geochemical techniques to better constrain what ice sheets may have looked like during the past warm times. He outlined methods of sampling bedrock along ice sheet margins (Barnes Ice Cap) that has become ice free in the last few years, and drilling through existing ice to sample bedrock currently resting beneath extant ice sheets (Greenland). He deftly described how geochemical measurements from these unique samples help determine how often in the recent geologic past the Laurentide and Greenland ice sheets completely disappeared. This work focused on recent results of a major project Greendrill as well as his ongoing projects on Baffin Island’s Barnes Ice Cap.

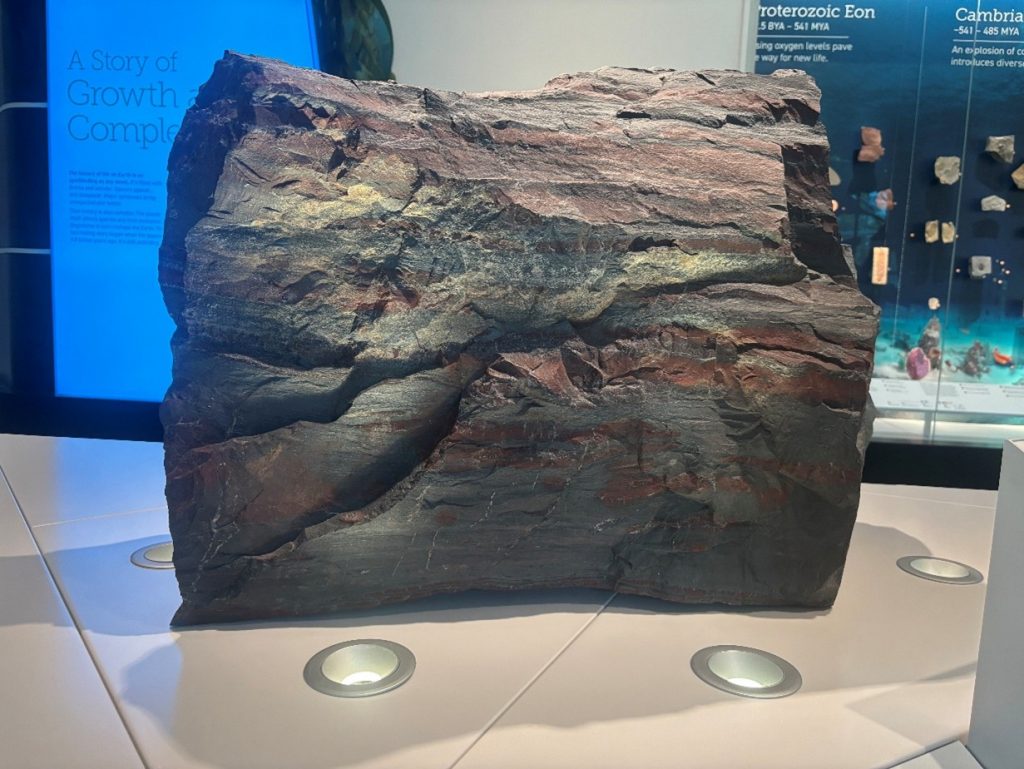

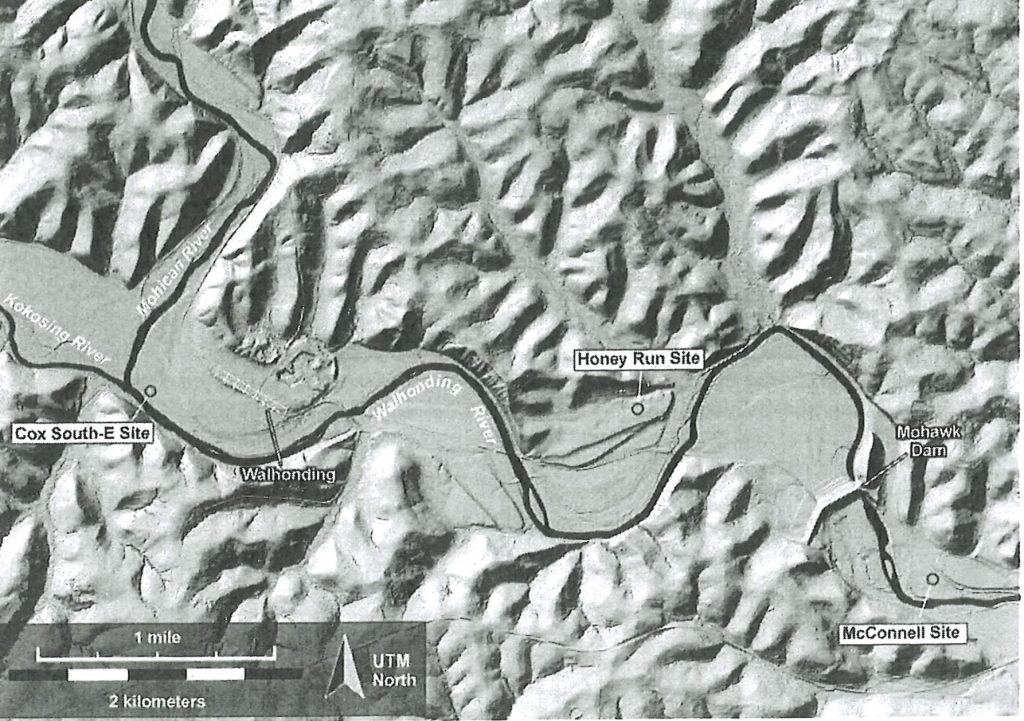

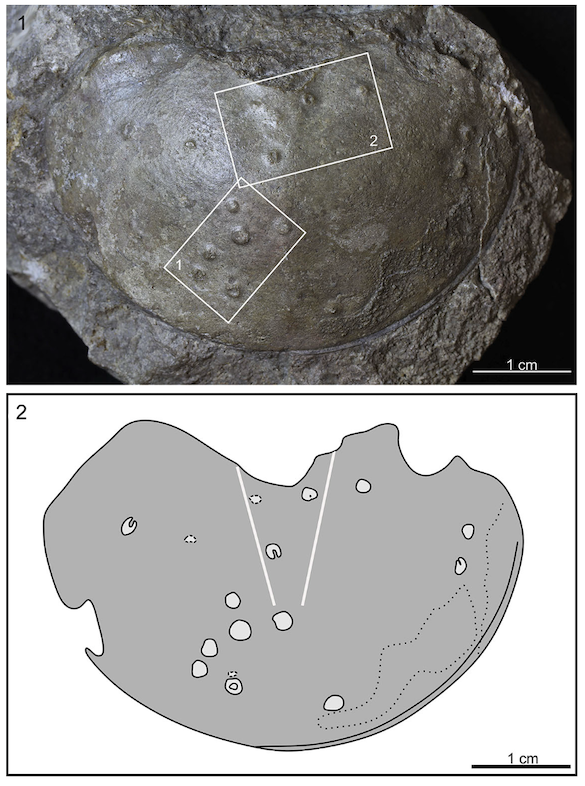

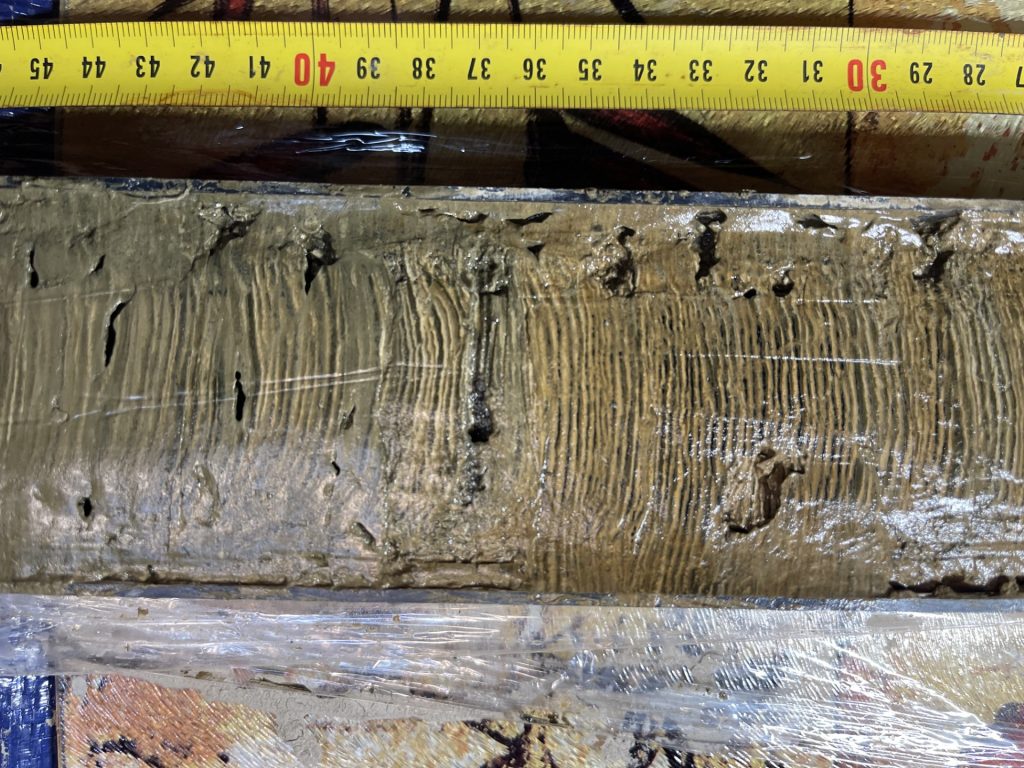

News to many in the audience is that the Laurentide Ice Sheet still exists as the remanent Barnes Ice Cap on Baffin Island in the Canadian Arctic. It was the Barnes Ice Cap and the fascinating story of its recent (the last few millennia) history that blew many of us away. Nicolás presented these recent results to our Geoclub. Note the trimline around the extent of the ice cap pictured above in this Sentinel image.

Nicolás speaking to Geoclub on his recent discoveries at the Barnes Ice Cap.

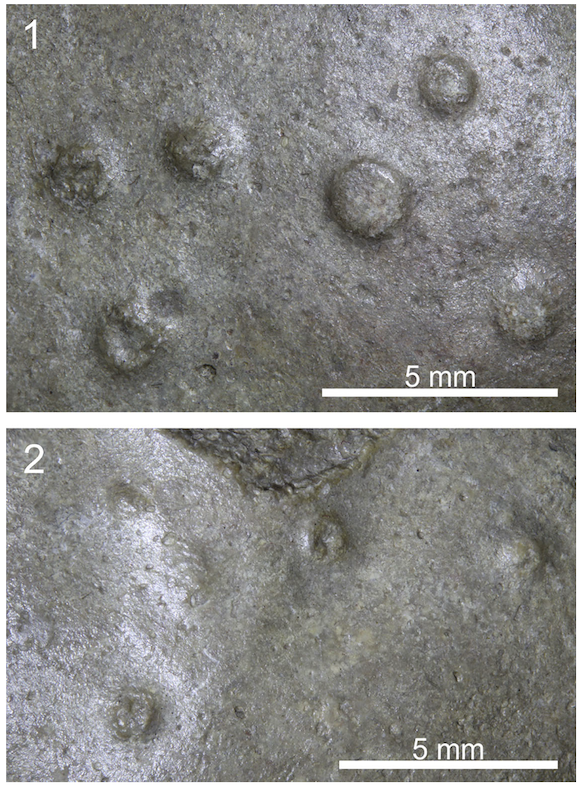

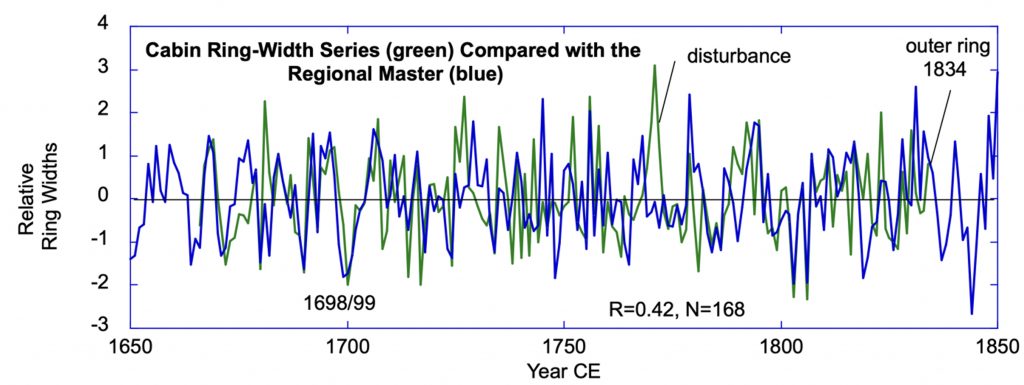

I can’t give the story away as the article is in review (I will post again when it comes out). The gray trimline area seen in the figure above marks a “recent” advance to this 1960 CE position, after which retreat has dominated. Nicolás described the trimline as a knife-edge and that only through careful dating using cosmogenic isotopes could one determine when this “recent” advance of ice began. The significance of this recent advance of the remanent of the Laurentide Icesheet is remarkable and transforms our thinking of Earth’s recent climate history.

We greatly thank the Osgood family for endowing the funds to bring innovative science to our Wooster community each year.

The Weather station active in the Arboretum since the late 1800s provided the monthly climate records.

The Weather station active in the Arboretum since the late 1800s provided the monthly climate records.