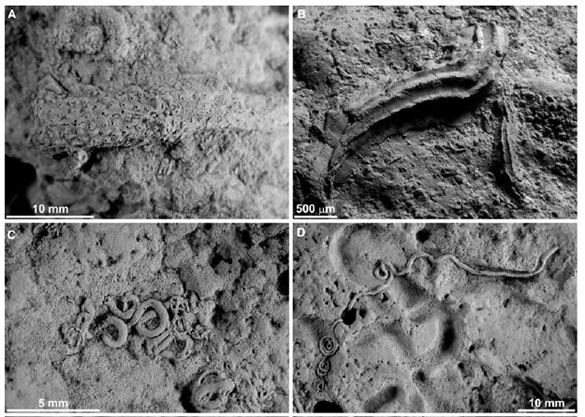

Bryozoans (the thin branching structures) and an edrioasteroid (with the "star") encrusting a hiatus concretion from the Kope Formation (Upper Ordovician) of northern Kentucky.

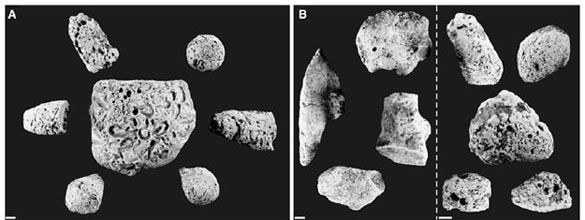

Way back in 1984, when I was just a green Assistant Professor of Geology, my wife Gloria and I explored a series of Upper Ordovician (about 445 million years old) outcrops in northern Kentucky to plan a paleontology course field trip. It was a rainy day were, as is too often the case, slippery with mud. On our last roadcut exposure of the day I stepped out of the car and found at my feet the cobble pictured above. It had edrioasteroid echinoderms and bryozoans encrusting it on all sides — and we knew we had found something special. We collected dozens of the cobbles in a few minutes. It changed my research trajectory by introducing me to the splendors of hard substrate communities and hiatus concretions.

This post is a celebration of another chapter of that work published next month in the journal Facies (volume 57, pp. 275-300). This time I’m a member of a large team led by my young friend and colleague Michal Zaton of the University of Silesia in Sosnowiec. We thoroughly examined a set of bored and encrusted cobbles from the Middle Jurassic (about 170 million years old) of south-central Poland. It was a pleasure to use some of the same research techniques I employed 26 years ago to help reconstruct an ancient ecosystem and environment.

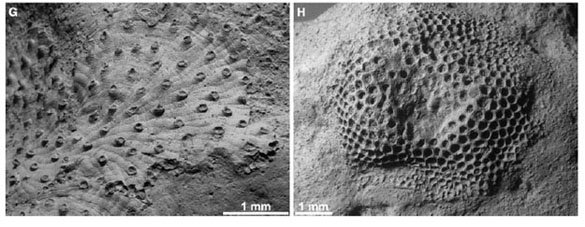

These cobbles are known as “hiatus concretions” because they collect in an environment when sediment has stopped (gone on “hiatus”, I suppose) and a lag of hard debris accumulates when fine sediment is washed away by currents. Organisms which require a hard substrate (“sclerobionts”) encrust the cobble surfaces (bryozoans, echinoderms, oysters and serpulid worms are most common) or bore into the matrix (sponges, bivalves, barnacles and worms commonly do this). A fossil record thus is formed in the absence of sedimentation, which is a bit different from the usual paradigm.

I enjoy studying marine hard substrate organisms through time because they show a type of community evolution over hundreds of millions of years. These diverse fossils have also provided countless research opportunities for my Wooster students, and tracking them down has taken us all over the world and throughout the geological column. (The Cretaceous of Israel is another recent example of this work.) It is very satisfying to see a young geologist like Michal Zaton finding pleasure and research success in the same pursuit.

great pictures of hard substrate communities! I worked on the Upper Ordovician of northern Georgia and although the focus was on diagenesis, this brings back a lot of memories..

Glad to have a message from you, Suvrat! You work in some very cool places.

Pingback: Wooster Geologists » Blog Archive » It is always a good day if there are sclerobionts in it

Pingback: Wooster Geologists » Blog Archive » Wooster’s Fossil of the Week: An edrioasteroid (Upper Ordovician of Kentucky)