DAYTON, OHIO–It was 37°F and raining this morning as three stalwart Wooster Geology students and I worked in a muddy quarry near Fairborn, Ohio (N 39.81472°, W 83.99471°). Our task was to scout out a beautiful exposure of the Brassfield Formation (Early Silurian, Llandovery) for a future field trip by the Sedimentology & Stratigraphy class. Until today this week was sunny and warm in Ohio. Nevertheless, our students persevered and efficiently measured and described the exposed units, and then they searched for glacial grooves and truncated corals on the top surface.

DAYTON, OHIO–It was 37°F and raining this morning as three stalwart Wooster Geology students and I worked in a muddy quarry near Fairborn, Ohio (N 39.81472°, W 83.99471°). Our task was to scout out a beautiful exposure of the Brassfield Formation (Early Silurian, Llandovery) for a future field trip by the Sedimentology & Stratigraphy class. Until today this week was sunny and warm in Ohio. Nevertheless, our students persevered and efficiently measured and described the exposed units, and then they searched for glacial grooves and truncated corals on the top surface.

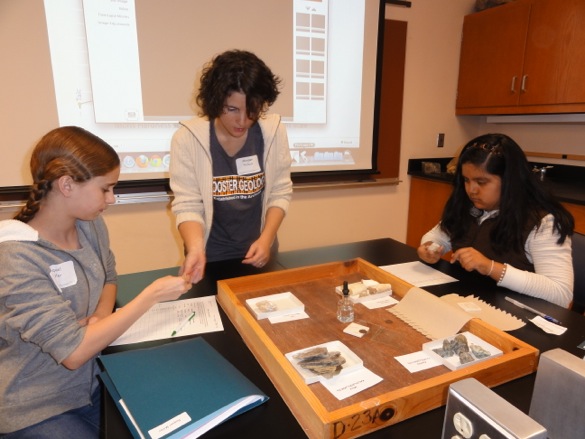

Abby, Steph and Lizzie during a relatively dry moment. The striped stick, by the way, is a Jacob’s Staff divided into tenths of meters. We use these large and simple rulers to measure the thickness of rock units. Our technician Matt Curren made us nice set of these this semester. Previous Wooster students may remember the long dowels we had in the past that Stephanie Jarvis discovered one day were not very precise! Why do we call them “Jacob’s Staffs”? Read Genesis 30:25-43. (This must be the first biblical reference in this blog!)

Abby, Steph and Lizzie during a relatively dry moment. The striped stick, by the way, is a Jacob’s Staff divided into tenths of meters. We use these large and simple rulers to measure the thickness of rock units. Our technician Matt Curren made us nice set of these this semester. Previous Wooster students may remember the long dowels we had in the past that Stephanie Jarvis discovered one day were not very precise! Why do we call them “Jacob’s Staffs”? Read Genesis 30:25-43. (This must be the first biblical reference in this blog!)

Dolomite at the base of the Brassfield with a pervasive fabric of burrows. These trace fossils were probably produced by shrimp-like arthropods tunneling in the seafloor sediments.

Dolomite at the base of the Brassfield with a pervasive fabric of burrows. These trace fossils were probably produced by shrimp-like arthropods tunneling in the seafloor sediments.

A well-sorted encrinite (limestone made almost entirely of crinoid skeletal fragments) from the lower third of the Brassfield Formation. These are mostly stem and arm pieces. The articulated portion on the left is a small stem.

A well-sorted encrinite (limestone made almost entirely of crinoid skeletal fragments) from the lower third of the Brassfield Formation. These are mostly stem and arm pieces. The articulated portion on the left is a small stem.

A poorly-sorted encrinite. Here you can see a much greater range of bioclast size than in the previous image. There are also some brachiopod shell fragments mixed in.

A poorly-sorted encrinite. Here you can see a much greater range of bioclast size than in the previous image. There are also some brachiopod shell fragments mixed in.

The Brassfield Formation is a critical one in stratigraphy because most of the other Silurian carbonates in northeastern North America have been altered by dolomitization, which destroys the original fabric and texture of the rock. Fossils become mere ghosts in dolomitized limestone, but here they are superbly preserved.

It may have been a damp and chilly day, but how bad could it have been if we had limestones and fossils in it?