One of my favorite trace fossils (fossils that record ancient behavior) is the ichnogenus Arachnostega. It was first formally described and named by Bertling in 1992, which is surprisingly recent for such a common fossil. This week my Estonian colleagues and I, led by Olev Vinn (University of Tartu) have a new paper showing it may be an indicator of ancient climate change (Vinn et al., 2025).

One of my favorite trace fossils (fossils that record ancient behavior) is the ichnogenus Arachnostega. It was first formally described and named by Bertling in 1992, which is surprisingly recent for such a common fossil. This week my Estonian colleagues and I, led by Olev Vinn (University of Tartu) have a new paper showing it may be an indicator of ancient climate change (Vinn et al., 2025).

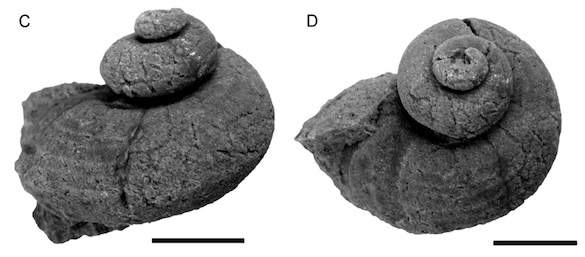

The taphonomy (preservation process) of Arachnostega is unusual. The top image on this page from Figure 2 in the new paper. It shows an internal mold of the gastropod Prosolarium from the Sheinwoodian stage of the middle Silurian. (The scale bar is one centimeter.) It was collected from Ninase Cliff on Saaremaa Island, Estonia. The preservation process started with the death of the snail and filling of its shell with muddy sediment. A very small soft-bodied organism then tunneled its way into the shell and began to work through the internal sediment like a modern earthworm, digesting the mud and extracting organic material from it. It left in its path a set of tunnels filled with the processed sediment. The trick with Arachnostega is that this trace maker fed at the boundary between the shell and sediment, always keeping in contact with the shell’s internal surface. This burrow system was exposed much later when the infilling sediment cemented up and the snail shell dissolved away, producing an internal mold of the shell with branching tunnels of Arachnostega on its outer surface. The shell was made of the carbonate mineral aragonite, which easily dissolved after burial.

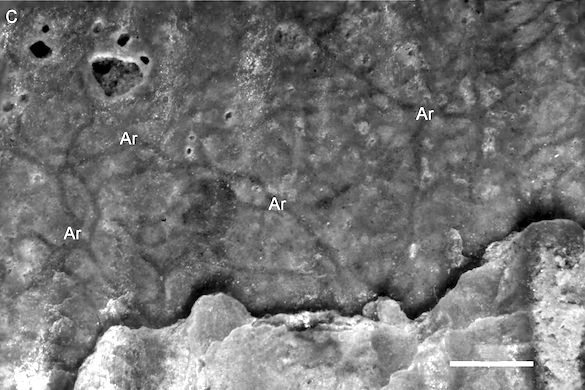

This image above is of Arachnostega burrows (marked “Ar”) in an internal mold of the brachiopod Estonirhynchia estonica, again from the Sheinwoodian of Saaremaa Island, this time from the Paramaja Coast. (Scale bar is one millimeter.) Again we see the web of burrows that were formed inside the shell against its inner surface. This time, though, the shell is made of calcite, a carbonate mineral that does not dissolve as easily as aragonite. Arachnostega is thus exposed only when the brachiopod shell is broken away. You can see remnants of the shell in the lower part of the image.

This image above is of Arachnostega burrows (marked “Ar”) in an internal mold of the brachiopod Estonirhynchia estonica, again from the Sheinwoodian of Saaremaa Island, this time from the Paramaja Coast. (Scale bar is one millimeter.) Again we see the web of burrows that were formed inside the shell against its inner surface. This time, though, the shell is made of calcite, a carbonate mineral that does not dissolve as easily as aragonite. Arachnostega is thus exposed only when the brachiopod shell is broken away. You can see remnants of the shell in the lower part of the image.

Bertling (1992) came up with the ichnogenus name Arachnostega by combining the Greek terms arachne (spider) and stega (roof, cave). Makes sense for a trace fossil with a web-like appearance that was formed in a shell cavity.

Now that we have the taphonomy of Arachnostega explained, we can best describe the significance of these recent finds with the paper’s abstract —

Arachnostega gastrochaenae burrows occur in internal molds of the brachiopod Estonirhynchia estonica in the Wenlock of Saaremaa, Estonia, and in gastropod steinkerns [= internal molds] in the Wenlock of Gotland, Sweden. The trace-making worms either entered the shell through the slit between the closed brachiopod valves as juveniles, or they used the brachiopod foramen to enter the shell interior. The Arachnostega traces in closed brachiopod shells are hidden until shell fragments are removed, exposing the internal mold. Because they are hidden in complete, articulated shells, Arachnostega may be more common in the Silurian of Baltica than currently recognized, though markedly less common than in the Ordovician. The trace makers responsible for burrows in brachiopods and gastropods presumably persisted from the Ordovician to the Silurian. The rarity of Arachnostega burrows in the Silurian of Baltica as compared to that of early Late Ordovician supports the view that, at least during the early Paleozoic, Arachnostega trace makers preferred colder climates.

Finally, the above gastropod internal mold with Arachnostega was photographed a decade ago by Olev Vinn. It is from the Ordovician of Estonia and was not part of this new study. It is beautiful, though, and shows this trace fossil well. Past Wooster paleontology students may recall seeing Arachnostega in their Ordovician fossil collections. Vinn et al. (2014) is a study of Ordovician Arachnostega in Estonia.

Finally, the above gastropod internal mold with Arachnostega was photographed a decade ago by Olev Vinn. It is from the Ordovician of Estonia and was not part of this new study. It is beautiful, though, and shows this trace fossil well. Past Wooster paleontology students may recall seeing Arachnostega in their Ordovician fossil collections. Vinn et al. (2014) is a study of Ordovician Arachnostega in Estonia.

References:

Bertling, M. 1992. Arachnostega n. ichnog. – burrowing traces in internal moulds of boring bivalves (late Jurassic, northern Germany). Paläontologische Zeitschrift 66: 177-185.

Vinn, O., Wilson, M.A., Isakar, M. and Toom, U. 2025. Rare Arachnostega traces in brachiopod and gastropod molds from the Silurian of Gotland (Sweden) and Saaremaa (Estonia): Was tropical climate unfavorable for the trace makers? Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie 313/2: 153–159. DOI: 10.1127/njgpa/2024/1226

Vinn, O., Wilson, M.A., Zatoń, M. and Toom, U. 2014. The trace fossil Arachnostega in the Ordovician of Estonia (Baltica). Palaeontologia Electronica Article number 17.3.40A.