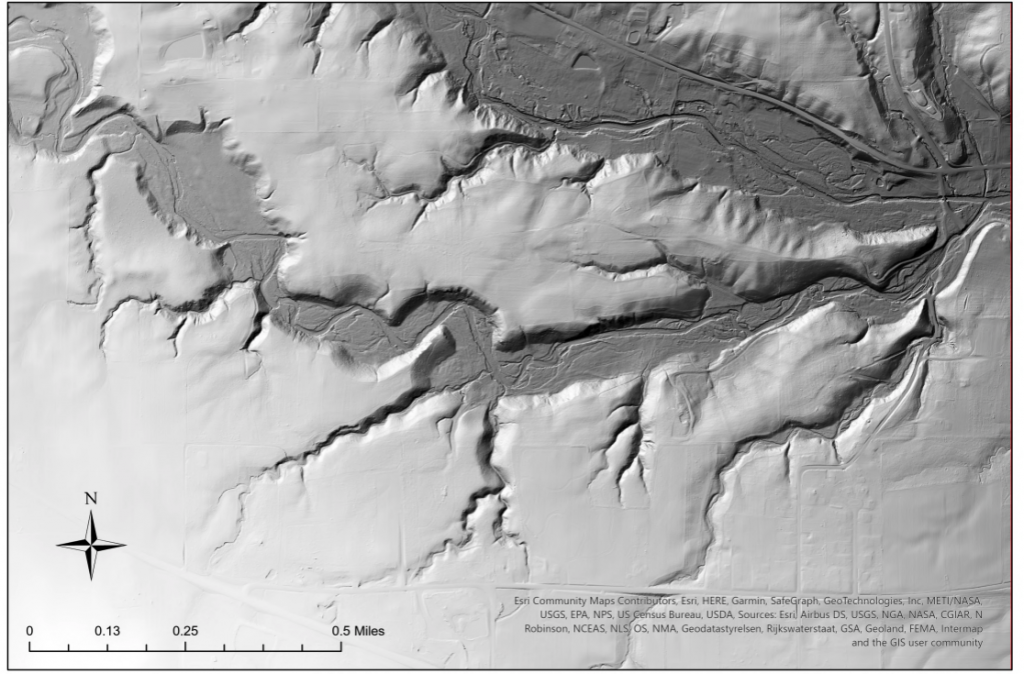

Guest bloggers: Damien, Rheo, Elliot and Arron: On September 9th the 2024 Fall Geomorphology Class took a trip to Spangler Gorge in Wooster Memorial Park. Here the students studied how the valley formed around Rathburn Run as well as the various unconformities that could be seen throughout the gorge. On a later trip the group visited a new site along the Little Killbuck River drainage and described the sediments in a delta built into glacial Lake Killbuck.

Figure 1. LiDAR map of the Wooster Memorial Park. The lower drainage is in Wooster Memorial Park (Rathburn Run) and the larger drainage to the north is the Little Killbuck drainage.

Figure 2. (above) The local Mississippian bedrock in the way into the gorge is creeping downhill due to unloading. (lower) Tree throw is a major sediment transport mechanism especially after some major storms over the last few years.

Figure 3. Once in the gorge the group discusses the various unconformities in the park. The drought early in the fall was evident with very low flow throughout the gorge.

Figure 4. A glacial erratic from Canada- the is from an outcrop to the Gowganda Tillite in Ontario. This dates back to the Snowball Earth interval in the Proterozoic and was brought down by various advances of the Laurentide Icesheet.

Figure 5. Unconformity (disconformity) with Holocene alluvium overlying the Mississippian bedrock. Note the knickpoint in the rock and its jointing.

Figure 6. Hayden pointing out an unconformity with holocene alluvium overlying a Pleistocene lodgement till.

Figure 7. Conjugate joint sets in the floor of the gorge – this angularity, in part, determines the zig-zag stream pattern of Rathburn Run as it continues to entrench into the bedrock.

Figure 8. Siltstone being undercut by Rathburn Run, note the varying structure of the rock contributing to a large range of rock strengths. This outcrop is an outlier in the gorge eroded by generations of ice ages and fluvial downcutting.

Figure 9. Debris cone at the base of the bedrock – these fans build in the dry fall and then get swept away with floods and incorporated in the alluvium.

Figure 10. A small alluvial fan built out into the valley alluvium. The fallen tree in the upper right has fallen along the long axis of the fan.

Figure 11. Debris flow at the unconformity with the bedrock and overlain by alluvium.

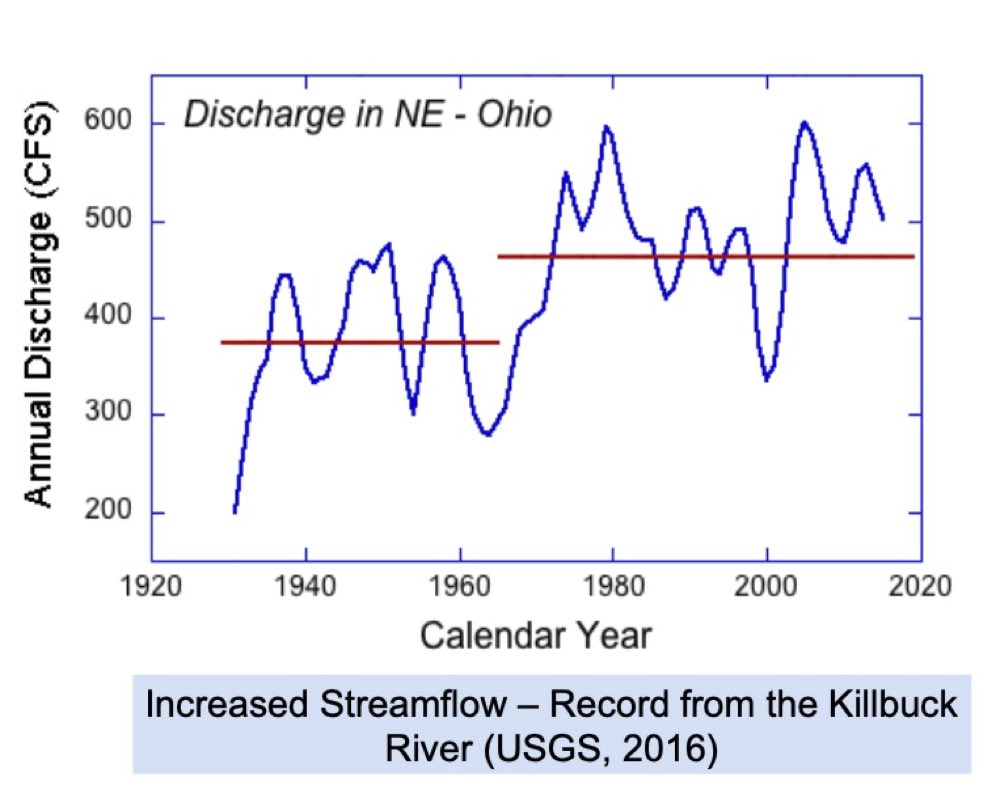

Erosion in Spangler Gorge has been rapidly increasing over the last several decades. A major factor driving this change seems to be due to climate change bringing in greater amounts of precipitation with more extreme weather patterns, often flooding the system with large amounts of water and increasing the stream’s strength and velocity. The increased strength of the stream (Figure 12) has led to it downcutting, and eventually being unable to reach its floodplains. Floodplains have an important role in managing the energy from flooding streams, allowing them to overflow, spread out, and slow down. However, now that the floodplains have become inaccessible, the high kinetic energy during a flood stays condensed within the streambed, leading to further erosion. Notably, this intensity causes undercutting to occur in the surrounding rocks which eventually causes them to become unstable and collapse, dumping more sediments into the rushing water. While a healthier stream system would be able to eventually rebuild its banks and reach its floodplains again, the velocity of the stream in Spangler erodes sediments faster than they can be deposited, leading only to more widening and downcutting of the streambed. It seems unlikely, with the intensifying climate of the area, that Spangler will be able to rebuild its banks on its own and become more stabilized. However, there could be opportunities in the future for stream restoration projects to try and reestablish healthier and stronger banks for the stream.

Figure 12. Discharge from the nearby Killbuck Creek. Rathburn Run is a tributary to the Killbuck. Note the shift in the mid-1970s to high annual streamflow. Our working hypthesis is that the rivers and streams in the NE Ohio region are now downcutting over the past few decades at faster rates than they have for several thousand years.

Well done, Geomorphology Team! I like the start with the high-resolution LiDAR map for contrast, and then the detailed analysis of the geomorphological processes in the context of climate change. I especially appreciate the sed/strat stories!