Gloria and I and our daughter Amy took advantage of the first days of Fall Break at Wooster to visit the Gettysburg Battlefield in Pennsylvania, about a 5.5 hour drive from home. The weather was spectacularly beautiful, as you can see in these images. The blue skies and bright sun made the place all the more heart-wrenching, though, considering the events of July 1-3, 1863, commemorated so vigorously here. This is one of the best maintained battlefield in the world, and one of the most visited. Over four million tourists (or, arguably, pilgrims) travel to this site in eastern Pennsylvania every year. They are greeted by more than 1200 monuments (“stone sentinels“) to this American Civil War battle. There were over 45,000 casualties on both sides, making it the bloodiest battle in North American history.

Gloria and I and our daughter Amy took advantage of the first days of Fall Break at Wooster to visit the Gettysburg Battlefield in Pennsylvania, about a 5.5 hour drive from home. The weather was spectacularly beautiful, as you can see in these images. The blue skies and bright sun made the place all the more heart-wrenching, though, considering the events of July 1-3, 1863, commemorated so vigorously here. This is one of the best maintained battlefield in the world, and one of the most visited. Over four million tourists (or, arguably, pilgrims) travel to this site in eastern Pennsylvania every year. They are greeted by more than 1200 monuments (“stone sentinels“) to this American Civil War battle. There were over 45,000 casualties on both sides, making it the bloodiest battle in North American history.

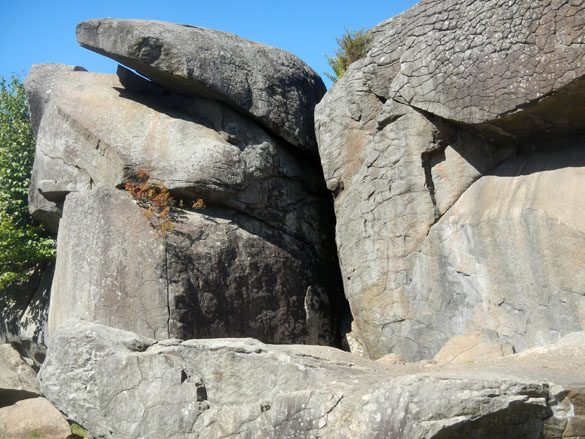

The geology of the Gettysburg battlefield is very well known, and much has been written about how the bedrock provided the dramatic setting and constrained the tactics of both sides. In a simple summary, during the Triassic break-up of the supercontinent Pangaea, rift basins occurred along what would become the northeastern margin of North America. A variety of sediments filled these widening valleys as the terrain around them eroded. The thinning crust below produced considerable igneous activity and these sediments were intruded by dikes and sills made of the igneous rock diabase. Diabase is very hard and resistant, so when this area was later eroded, the igneous bodies stood in relief from the softer materials around them, forming rocky hills and ridges. In the top image we see this diabase exposed at a place on the battlefield known as Devil’s Den. During the battle the Union forces occupied most of the high ground underlain by these diabase rocks, including iconic names like Little Round Top, Cemetery Ridge and Culp’s Hill.

I have no intent of telling the story of the Gettysburg battle here. What follows are just a few images of the places most meaningful to me.

It is at Devil’s Den that we see the best exposures of the diabase. This place was occupied by Confederates during most of the battle, and is probably most famous for the photographs of Confederate dead. The top surfaces of these rocks are worn slick by the shoes of visitors over the past 150 years.

It is at Devil’s Den that we see the best exposures of the diabase. This place was occupied by Confederates during most of the battle, and is probably most famous for the photographs of Confederate dead. The top surfaces of these rocks are worn slick by the shoes of visitors over the past 150 years.

The hard diabase was immediately useful to Union troops, who constructed these low stone breastworks across the western slopes of Little Round Top, Cemetery Ridge and Culp’s Hill. The bedrock is very close to the surface, so it was impossible to dig useful trenches or foxholes.

The hard diabase was immediately useful to Union troops, who constructed these low stone breastworks across the western slopes of Little Round Top, Cemetery Ridge and Culp’s Hill. The bedrock is very close to the surface, so it was impossible to dig useful trenches or foxholes.

The focus of my pilgrimage every time I visit Gettysburg is Little Round Top, seen here from Devil’s Den looking eastward. In one of the most dramatic actions of the battle, college professor Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain led his men of the 20th Maine in a desperate bayonet charge downhill into advancing Confederates. This surprising action on the second day, for which Colonel Chamberlain won the Congressional Medal of Honor, stopped the Confederate assault on the far left of the Union line, saving it from collapse. That decision to charge, and the Maine men’s willingness to do it, likely saved the battle for the Union, and maybe even the war.

The focus of my pilgrimage every time I visit Gettysburg is Little Round Top, seen here from Devil’s Den looking eastward. In one of the most dramatic actions of the battle, college professor Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain led his men of the 20th Maine in a desperate bayonet charge downhill into advancing Confederates. This surprising action on the second day, for which Colonel Chamberlain won the Congressional Medal of Honor, stopped the Confederate assault on the far left of the Union line, saving it from collapse. That decision to charge, and the Maine men’s willingness to do it, likely saved the battle for the Union, and maybe even the war.

This is the monument to the 20th Maine at the charge site on Little Round Top.

This is the monument to the 20th Maine at the charge site on Little Round Top.

Above is a view from the Union line on Cemetery Ridge westward across the fields to Seminary Ridge, which was occupied by the Confederates. On the third and last day of the battle, General Robert E. Lee ordered General James Longstreet to organize a general attack across these fields against the center of the Union line here. This is known to history as Pickett’s Charge. It was a foolish move, and everyone but Lee seemed to know that it was a hopeless, murderous gesture. The failure of this charge marked the end of the battle. General Lee retreated the next day.

Above is a view from the Union line on Cemetery Ridge westward across the fields to Seminary Ridge, which was occupied by the Confederates. On the third and last day of the battle, General Robert E. Lee ordered General James Longstreet to organize a general attack across these fields against the center of the Union line here. This is known to history as Pickett’s Charge. It was a foolish move, and everyone but Lee seemed to know that it was a hopeless, murderous gesture. The failure of this charge marked the end of the battle. General Lee retreated the next day.

I was taken by this unusual monument to the 20th Massachusetts Infantry, which was one of the Union units that repulsed Pickett’s Charge on the third day of battle. Rather than statuary, the veterans of the 20th Massachusetts chose to transport a large rock from a neighborhood of Boston to be placed on their spot of the battlefield. The message was, of course, that here stood men of Massachusetts rock who could not be moved.

I was taken by this unusual monument to the 20th Massachusetts Infantry, which was one of the Union units that repulsed Pickett’s Charge on the third day of battle. Rather than statuary, the veterans of the 20th Massachusetts chose to transport a large rock from a neighborhood of Boston to be placed on their spot of the battlefield. The message was, of course, that here stood men of Massachusetts rock who could not be moved.

The rock is known as Roxbury Puddingstone, more formally called the Roxbury Conglomerate. It is the official state rock of Massachusetts. (Do you know your state rock?)

The rock is known as Roxbury Puddingstone, more formally called the Roxbury Conglomerate. It is the official state rock of Massachusetts. (Do you know your state rock?)

This rock contains a jumble of clasts of different sizes and maybe a dozen compositions. It is Ediacaran in age and likely accumulated in deep-sea fans as turbidites that formed when gravity-driven slurries of sediment flowed down submarine slopes. Or you can believe another story told in an 1830 poem by the future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., called “The Dorchester Giant“, who fed his rowdy family “a pudding stuffed with plums” that they flung about, leaving us the fossil evidence. Holmes served as an officer in the 20th Massachusetts.

This rock contains a jumble of clasts of different sizes and maybe a dozen compositions. It is Ediacaran in age and likely accumulated in deep-sea fans as turbidites that formed when gravity-driven slurries of sediment flowed down submarine slopes. Or you can believe another story told in an 1830 poem by the future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., called “The Dorchester Giant“, who fed his rowdy family “a pudding stuffed with plums” that they flung about, leaving us the fossil evidence. Holmes served as an officer in the 20th Massachusetts.

References:

Brown, A. 2006. Geology and the Gettysburg Campaign. Pennsylvania Geological Survey Educational Series 5, published by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania/Department of Conservation and Natural Resources/ Bureau of Topographic and Geological Survey: 14 pp.

Murray, J.M. 2014. On a Great Battlefield: The Making, Management, and Memory of Gettysburg National Military Park, 1933–2012. Univ. of Tennessee Press.

Newman, R.J. 2015. When the secular is sacred: The Memorial Hall to the Victims of the Nanjing Massacre and the Gettysburg National Military Park as pilgrimage sites. Global Secularisms in a Post-Secular Age 2: 261-270.

Weeks, J. 1998. Gettysburg: Display window for popular memory. The Journal of American Culture 21: 41-56.

Weeks, J. 2003. Gettysburg: Memory, market, and an American shrine. Princeton University Press.

All new to me – great to see the Roxbury Puddingstone, Theresa’s home town rock (and state rock as well).

The ugliest monument on the field, the most beautiful monument at Gettysburg, the 20th Massachusetts Roxbury Conglomerate. This ancient stone was from a rock playground around Boston and later transported to the battlefield marking the spot where those who frolicked in youth fought and held the line during Pickett’s Charge.

Clasts and pebbles, boulders all of diverse lithologies from disparate terrains were tumbled together and locked in a complex matrix. Pressure and heat with the flux of chemistry indurated the Roxybury Conglomerate. Soldiers of the 20th Massachusetts Regiment also represented diversity tumbled together through a nation’s convulsive war. They found unity in the heat and pressure cauldron of this battle, bonded forever.

(It was also noted that stone bases for all Confederate monuments on the Gettysburg battlefield are cut from Rapakivi granites, the mantle of Ca-Na feldspars cloaking orthoclase cores)

You need to educate the National Park Service. Their writeups of the geology of the field are pathetic. They contradict themselves in a single sentence and impart nonsense to the unknowledgeable reader such as diabase being the same as granite. That’s news to me. I guess that is what you get when you give people a uniform and they think they know something. I heard the same kind of ill informed tripe coming out of the uniformed docent’s at numberous national parks when it came to things geologic.

As a geologist of 40 years experience with a background in igneous geology, I appreciated your article.

Thanks, Keith. I’m laughing at that comment of diabase being the same as granite. I’d be run out of town by my colleagues if I even implied that! Thanks for your kind words. We are educators to the end in an awesome field.

That’s really interesting something you don’t think about how geology played a role in the battle.