On July 3, 1754, colonial lieutenant Colonel George Washington fought and lost a small battle on this site in southwestern Pennsylvania. He and his 400 men had built this makeshift fort about a month before in anticipation of an attack by several hundred French soldiers and their Indian allies. The French were incensed at Washington and his troops after they killed or captured most of a French party at the Battle of Jumonville Glen two months before. (Accounts vary as to who was at fault for that deadly encounter as France and Britain were not at war.) The Battle of Fort Necessity was just one day long, and the British under Washington had the worst of it. Washington accepted French surrender terms and he and his men were allowed to march home. This pair of skirmishes between the French and British started the French and Indian War, known outside of the USA as the Seven Years’ War. It quickly became a global fight between empires; in many ways it was the first modern world war. And it all started in this lonely part of the Pennsylvania country.

On July 3, 1754, colonial lieutenant Colonel George Washington fought and lost a small battle on this site in southwestern Pennsylvania. He and his 400 men had built this makeshift fort about a month before in anticipation of an attack by several hundred French soldiers and their Indian allies. The French were incensed at Washington and his troops after they killed or captured most of a French party at the Battle of Jumonville Glen two months before. (Accounts vary as to who was at fault for that deadly encounter as France and Britain were not at war.) The Battle of Fort Necessity was just one day long, and the British under Washington had the worst of it. Washington accepted French surrender terms and he and his men were allowed to march home. This pair of skirmishes between the French and British started the French and Indian War, known outside of the USA as the Seven Years’ War. It quickly became a global fight between empires; in many ways it was the first modern world war. And it all started in this lonely part of the Pennsylvania country.

Washington chose to place his ill-fated fort, a reconstruction of which is shown above, in a high grassy spot known as the Great Meadows. It is situated near two passes in the Allegheny Mountains, and thus sits strategically beside major trails. Washington liked the area because there was plenty of feed for his pack animals and horses, lots of available water (too much, it turned out), and it was not in the midst of the endless woods of the region.

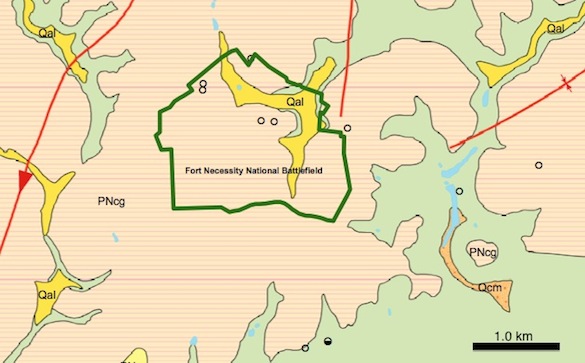

This geological map of the area (from the National Park Service) shows that the fort was situated on the Upper Carboniferous Glenshaw Formation. This unit has much clay, trapping water in the thin soil above (“Philo Loam“). Further, the area is a floodplain, thus making the area a kind of wetland with grasses and sedges. Great for horse grazing, not so good for walls, buildings or trenches.

This geological map of the area (from the National Park Service) shows that the fort was situated on the Upper Carboniferous Glenshaw Formation. This unit has much clay, trapping water in the thin soil above (“Philo Loam“). Further, the area is a floodplain, thus making the area a kind of wetland with grasses and sedges. Great for horse grazing, not so good for walls, buildings or trenches.

Here we see the shallow entrenchments made by Washington and his men as they awaited attack. The clayey soil and pouring rain made a mess of these boggy trenches.

Here we see the shallow entrenchments made by Washington and his men as they awaited attack. The clayey soil and pouring rain made a mess of these boggy trenches.

Inside the fort was a simple square building used mainly to keep supplies and wounded men dry, During the battle it was partially flooded with rainwater.

Inside the fort was a simple square building used mainly to keep supplies and wounded men dry, During the battle it was partially flooded with rainwater.

This is the British view from the fort of the surrounding woods. Washington miscalculated his placing of the fort because the French and Indians could easily hit it with musket shots while hiding among the trees.

This is the British view from the fort of the surrounding woods. Washington miscalculated his placing of the fort because the French and Indians could easily hit it with musket shots while hiding among the trees.

The French and Indian view of the hapless fort. It was easy to rain bullets on the British from the woods with little fear of the return fire.

The French and Indian view of the hapless fort. It was easy to rain bullets on the British from the woods with little fear of the return fire.

Nearby is a trace of the military road Washington’s unit had blazed through the Pennsylvania woods on their way to the French Fort Duquesne in what is now Pittsburgh. The British General Edward Braddock enlarged this road the next year in his famous march to a spectacular defeat nearby (the “Battle of Monongahela“).

Nearby is a trace of the military road Washington’s unit had blazed through the Pennsylvania woods on their way to the French Fort Duquesne in what is now Pittsburgh. The British General Edward Braddock enlarged this road the next year in his famous march to a spectacular defeat nearby (the “Battle of Monongahela“).

We can’t fault Washington too much for his choice of a fort location. He did not have the resources to clear a large patch of forest, so the meadow would have to do. He expected to be reinforced soon, so he saw the fort as a temporary measure of protection. The rain was beyond his control that July day, and the clay-rich meadow floor ensured wet misery and ruined supplies. The French surprisingly gave good terms for surrender because they were wet, too, in those woods, and they also expected more British and colonial troops would arrive soon. They feared being surrounded, and so thought their message to Washington and his countrymen had been sufficiently made. How different our world would be if the French were not so generous here in southwestern Pennsylvania!

Additional Reference:

Thornberry-Ehrlich, T. 2009. Fort Necessity National Battlefield Geologic Resources Inventory Report. Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/082. National Park Service, Denver, Colorado.