Geology, of course, is so much our fundamental basis for being that we rarely think about it. Occasionally, though, particular geological circumstances play direct roles in history. Today as I was visiting Góra Świętej Anny with my geologist friends I was intrigued by events that took place here in 1921 that provided another twist in the story that leads to the cataclysm of World War II.

Geology, of course, is so much our fundamental basis for being that we rarely think about it. Occasionally, though, particular geological circumstances play direct roles in history. Today as I was visiting Góra Świętej Anny with my geologist friends I was intrigued by events that took place here in 1921 that provided another twist in the story that leads to the cataclysm of World War II.

The image at the top is from Google Earth showing the low prominence of Góra Świętej Anny in the center. It is not particularly high (just 406 meters), but it dominates the surrounding low countryside of fertile fields, productive mines, and scattered factories. As noted in our previous blog entry, Góra Świętej Anny is elevated because it has a core of resistant basalt from an extinct Paleogene volcano. It was an isolated volcano (the furthest eastern exposed basalt in Europe) and thus forms an isolated hill.

This is a view west from Góra Świętej Anny. The haze in the background is from large smokestacks on the right.

This is a view west from Góra Świętej Anny. The haze in the background is from large smokestacks on the right.

On Góra Świętej Anny is the above monument to Polish Silesians who rebelled against the Germans throughout history (Teutonic knights are portrayed on the right panel), particularly during a 1921 battle on this elevation. The monument was dedicated in 1955 during “communist times” and shows many elements of Soviet-style design. It contains within it ashes from Poles killed in the Warsaw Uprising in 1945, and it is on the site of a German mausoleum that was dynamited to oblivion during liberation in 1945.

On Góra Świętej Anny is the above monument to Polish Silesians who rebelled against the Germans throughout history (Teutonic knights are portrayed on the right panel), particularly during a 1921 battle on this elevation. The monument was dedicated in 1955 during “communist times” and shows many elements of Soviet-style design. It contains within it ashes from Poles killed in the Warsaw Uprising in 1945, and it is on the site of a German mausoleum that was dynamited to oblivion during liberation in 1945.

These lead outlines represent Polish workers advancing against German troops in 1921 on Góra Świętej Anny. It is a story too complex for a blog entry, but here was the Battle of Annaberg between German Silesians and Polish Silesians during the Third Silesian Uprising. The Poles had taken this hill and defended it against an attack of German Freikorps, which were essentially World War I soldiers who had refused to demobilize in the chaos following the Armistice. The Poles were eventually forced off Góra Świętej Anny at great cost to the Germans. Later international commissions then divided up Silesia between Germans and Poles, with this area falling to the Germans. Polish Silesians, of course, took this very hard and continued to resist the Germans. Tension in this area eventually fed into pretexts for the German invasion of Poland in 1939, the start of World War II.

These lead outlines represent Polish workers advancing against German troops in 1921 on Góra Świętej Anny. It is a story too complex for a blog entry, but here was the Battle of Annaberg between German Silesians and Polish Silesians during the Third Silesian Uprising. The Poles had taken this hill and defended it against an attack of German Freikorps, which were essentially World War I soldiers who had refused to demobilize in the chaos following the Armistice. The Poles were eventually forced off Góra Świętej Anny at great cost to the Germans. Later international commissions then divided up Silesia between Germans and Poles, with this area falling to the Germans. Polish Silesians, of course, took this very hard and continued to resist the Germans. Tension in this area eventually fed into pretexts for the German invasion of Poland in 1939, the start of World War II.

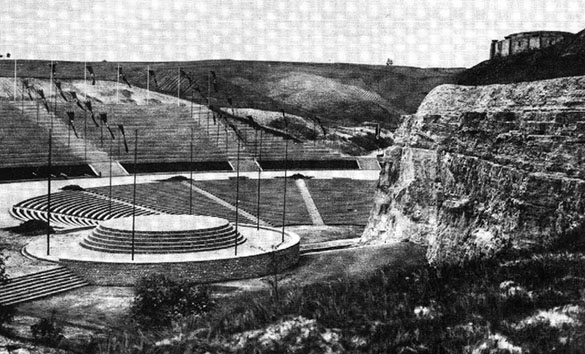

German nationalists, many of them early members of the Nazi Party, wanted to make Góra Świętej Anny (or Annaberg, as they called it) a kind of shrine to their past and future efforts to make Silesia part of the Reich. They built a mausoleum (seen in the top right in this pre-war image) and a large amphitheater called a Thingstätte. The idea was to have Nazi rallies here with the dead from 1921 elevated above in some sort of Valhalla. The excavation of the amphitheater is what exposed the Middle Triassic Muschelkalk rocks for our study today.

German nationalists, many of them early members of the Nazi Party, wanted to make Góra Świętej Anny (or Annaberg, as they called it) a kind of shrine to their past and future efforts to make Silesia part of the Reich. They built a mausoleum (seen in the top right in this pre-war image) and a large amphitheater called a Thingstätte. The idea was to have Nazi rallies here with the dead from 1921 elevated above in some sort of Valhalla. The excavation of the amphitheater is what exposed the Middle Triassic Muschelkalk rocks for our study today.

The amphitheater today survives for Polish festivals (it is a delight to hear the ring of schoolchildren’s voices here) and visiting geologists. (It is part of a geological interpretive trail). At the top of this view is the 1955 Polish monument on the site of the destroyed Nazi mausoleum.

The amphitheater today survives for Polish festivals (it is a delight to hear the ring of schoolchildren’s voices here) and visiting geologists. (It is part of a geological interpretive trail). At the top of this view is the 1955 Polish monument on the site of the destroyed Nazi mausoleum.

The Germans cut most of the trees of the area down when they made the amphitheater. The Poles have allowed the forest to return. There is something profound about the peaceful, natural healing this reforestation represents.

The Germans cut most of the trees of the area down when they made the amphitheater. The Poles have allowed the forest to return. There is something profound about the peaceful, natural healing this reforestation represents.