This week’s fossil is another from the collection made in 1996 on a Keck Geology Consortium expedition to Cyprus with Steve Dornbos as a Wooster student. Steve and I found a spectacular undescribed coral reef in the Nicosia Formation (Pliocene) near the village of Meniko (N 35° 5.767′, E 33° 8.925′). Finding a reef was a surprise because the unit is mostly quartz silt, which is not a sediment you usually associate with coral reefs. It was an advantage, though, because the silt was poorly lithified and could be easily removed from the fossils. The significance of this reef was that it represents the early recovery of marine faunas following the Messinian Salinity Crisis and the later refilling of the Mediterranean basin (the Zanclean Flood). Steve and I published our observations and analyses of this reef community in 1999.

This week’s fossil is another from the collection made in 1996 on a Keck Geology Consortium expedition to Cyprus with Steve Dornbos as a Wooster student. Steve and I found a spectacular undescribed coral reef in the Nicosia Formation (Pliocene) near the village of Meniko (N 35° 5.767′, E 33° 8.925′). Finding a reef was a surprise because the unit is mostly quartz silt, which is not a sediment you usually associate with coral reefs. It was an advantage, though, because the silt was poorly lithified and could be easily removed from the fossils. The significance of this reef was that it represents the early recovery of marine faunas following the Messinian Salinity Crisis and the later refilling of the Mediterranean basin (the Zanclean Flood). Steve and I published our observations and analyses of this reef community in 1999.

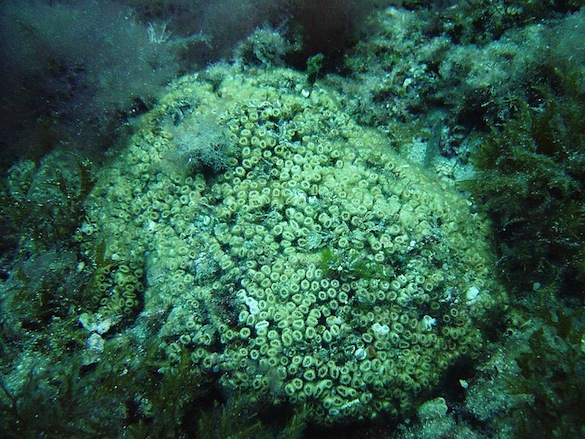

The coral is a species of the genus Cladocora Ehrenberg, 1834. This genus, a member of the Family Caryophylliidae, ranges from the Late Cretaceous to today, so it is a hardy group. This may be because it is unusually diverse in its habits, ranging from the shallow subtidal down to at least 480 meters, and including both zooxanthellate (containing symbiotic photosynthesizing organisms called zooxanthellae) and azooxanthellate (with no such symbionts) species. Since our fossils lived in shallow water, they were almost certainly zooxanthellate.

Cladocora is still found today in the Mediterranean (see the above Cladocora caespitosa). Like all zooxanthellate scleractinian corals, these shallow species of Cladocora obtain their nutrition from the byproducts of their photosynthetic symbionts and a diet of small animals (mostly arthropods and larvae) they collect with their tentacles. These tentacles are lined with “stinging cells” called nematocysts.

Our Pliocene Cladocora formed the framework of a reef at least six meters high and 50 meters wide. It had many shelled organisms living entwined in the branches of the coral, like the bivalve Spondylus pictured above. You can see the corallites (individual tubes) embedded in the shell.

Our Pliocene Cladocora formed the framework of a reef at least six meters high and 50 meters wide. It had many shelled organisms living entwined in the branches of the coral, like the bivalve Spondylus pictured above. You can see the corallites (individual tubes) embedded in the shell.

Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg (1795-1876) named the genus Cladocora from specimens in the Red Sea. He was a German naturalist and explorer who is often credited with founding the field of micropaleontology (the study of microfossils such as foraminiferans, ostracodes and diatoms). He earned an M.D. at the University of Berlin and remained on the university staff for his entire career. He was no homebody, though, traveling as a scientist throughout the Mediterranean and Middle East, Central Asia and Siberia. (His first expedition to the Middle East was an adventure, as you can read at the link.) He was the first to prove that fungi reproduce via spores, to describe the anatomy of corals, and to identify plankton as the source for marine phosphorescence. Ehrenberg was also the first to discover microfossils in rocks, noting that some rocks (like chalk) are made almost entirely of them. His best known books include Reisen in Aegypten, Libyen, Nubien und Dongola (1828; “Travels in Egypt, Libya, Nubia and Dongola”) and Die Infusionsthierchen als volkommene Organismen (1838; “The Infusoria as Complete Organisms”). That last concept (“volkommene Organismen” or “complete organisms”) was his idea that even the smallest organisms had all the working organs of the largest. That one didn’t go so well!

Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg (1795-1876) named the genus Cladocora from specimens in the Red Sea. He was a German naturalist and explorer who is often credited with founding the field of micropaleontology (the study of microfossils such as foraminiferans, ostracodes and diatoms). He earned an M.D. at the University of Berlin and remained on the university staff for his entire career. He was no homebody, though, traveling as a scientist throughout the Mediterranean and Middle East, Central Asia and Siberia. (His first expedition to the Middle East was an adventure, as you can read at the link.) He was the first to prove that fungi reproduce via spores, to describe the anatomy of corals, and to identify plankton as the source for marine phosphorescence. Ehrenberg was also the first to discover microfossils in rocks, noting that some rocks (like chalk) are made almost entirely of them. His best known books include Reisen in Aegypten, Libyen, Nubien und Dongola (1828; “Travels in Egypt, Libya, Nubia and Dongola”) and Die Infusionsthierchen als volkommene Organismen (1838; “The Infusoria as Complete Organisms”). That last concept (“volkommene Organismen” or “complete organisms”) was his idea that even the smallest organisms had all the working organs of the largest. That one didn’t go so well!

References:

Cowper Reed, F.R. 1935. Notes on the Neogene faunas of Cyprus, III: the Pliocene faunas. Annual Magazine of Natural History 10 (95): 489-524.

Cowper Reed, F.R. 1940. Some additional Pliocene fossils from Cyprus. Annual Magazine of Natural History 11 (6): 293-297.

Dornbos, S.Q. and Wilson, M.A. 1999. Paleoecology of a Pliocene coral reef in Cyprus: Recovery of a marine community from the Messinian Salinity Crisis. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 213: 103-118.