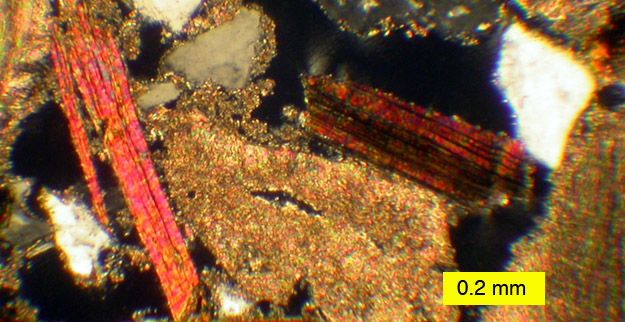

A beautiful view of a modern hardground in thin-section with cross-polarized light. The platy pinkish and brown grains are the minerals muscovite and biotite (micas), the gray and white angular grains are quartz, and the tan irregular grains are recrystallized shells and cements. Sample dredged from about 650 meters in the Strait of Messina between the Italian mainland and Sicily. Collected by Agostina Vertino.

WOOSTER, OHIO–Bitterly cold Ohio days are perfect for geological lab work, especially with thin-sections under a warm microscope accompanied by a music-filled iPod. The next best thing to fieldwork. A thin-section is a slice of polished rock glued to a microscope slide and then ground down to a standard thickness of 30 microns so that light easily passes through it. Minerals, fossils and other internal features become visible in a thin-section which would otherwise go unnoticed in the hand sample. We use polarized light to reveal optical properties of the crystals for identification and analysis. Often a thin-section in cross-polarized light shows an astonishing array of colors, fabrics and textures.

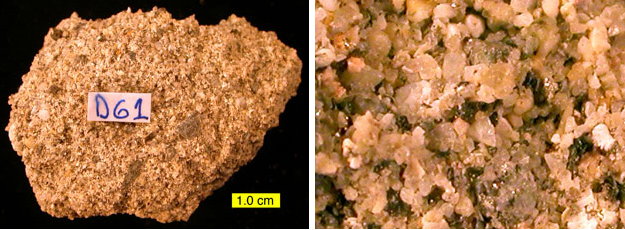

What is most fun is to take a drab rock and find the microscopic treasures within through thin-sectioning. For example, this is the rock I worked with today:

A hardground (cemented seafloor) sample from the Strait of Messina (the same rock as seen in the thin-section above). This sample was dredged from the deep-sea and is encrusted by the coral Desmophyllum dianthus and tiny tubeworms. Collected by Agostina Vertino.

A sample of the same hardground as above with the organic material removed. On the right is a closer view of the sand-sized grains making up the rock. Notice that even in this view you can tell that the grains are poorly cemented to each other.

An Italian colleague (Agostina Vertino of the Dipartimento Scienze Geologiche – Università Catania) and I are examining these unusual hardgrounds from deep in the underwater canyon at the bottom of the Strait of Messina. This is a very energetic system (the currents are fast), so the grain size is surprisingly coarse for a deep-water deposit. The composition of the sediment is highly variable, ranging from feldspars and micas to shell fragments and microscopic skeletons of foraminiferans. Our first question is the simplest: How are these sediments cemented? The thin-sections show us.

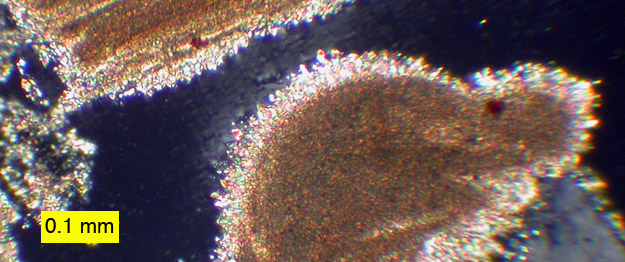

Carbonate rock fragments in the Strait of Messina hardground showing a thin fringe of calcareous crystals (probably aragonite) precipitated on their edges. The cement is formed when these crystalline fringes intersect and hold the grains together.

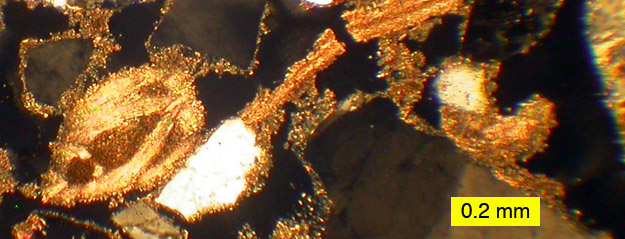

As you would expect, a rock so lightly cemented crumbles easily, and it has a very high porosity and permeability. It is remarkable that such an unstable substrate serves so well as an attachment surface for encrusting organisms such as corals, tubeworms, bryozoans and sponges.

The black areas in this thin-section view (as in the others) are open spaces. This particular hardground is highly porous and permeable. Note the bright fringing cements on the grains.

The porosity and permeability of this sediment is undoubtedly a key to its cementation. Fluids could move quickly and in considerable volume through this deposit, gradually precipitating the tiny, tiny calcareous crystals on the exposed grain surfaces. It is also possible that dissolving aragonite shells in the sediment supplied the necessary carbonate for the cement. There is much work ahead to figure that one out.

We will post more portraits of our geological laboratory studies this winter as we simultaneously prepare for next summer’s fieldwork. This is the life!