The view above, one quite familiar to me, is of a carbonate hardground from the Upper Ordovician Corryville Formation exposed near Washington, Mason County, Kentucky. We are looking directly at the bedding plane of this limestone. The lumpy, spotted fossil covering about half the surface is a trepostome bryozoan. It looks like a dollop of thick pudding plopped on the rock. In the upper left are round holes that are openings of the trace fossil Trypanites, a common boring in carbonate hard substrates.

The view above, one quite familiar to me, is of a carbonate hardground from the Upper Ordovician Corryville Formation exposed near Washington, Mason County, Kentucky. We are looking directly at the bedding plane of this limestone. The lumpy, spotted fossil covering about half the surface is a trepostome bryozoan. It looks like a dollop of thick pudding plopped on the rock. In the upper left are round holes that are openings of the trace fossil Trypanites, a common boring in carbonate hard substrates.

This closer view shows the bryozoan details in the right half. You can barely pick out the tiny pin holes of the zooecia (the tubes that contained the individual zooids) and see the raised areas called maculae, which may have assisted in directing water currents for these colonial filter-feeders. Without a thin-section or peel I can’t identify the bryozoan beyond trepostome. The Trypanites borings in the hardground surface are also visible.

This closer view shows the bryozoan details in the right half. You can barely pick out the tiny pin holes of the zooecia (the tubes that contained the individual zooids) and see the raised areas called maculae, which may have assisted in directing water currents for these colonial filter-feeders. Without a thin-section or peel I can’t identify the bryozoan beyond trepostome. The Trypanites borings in the hardground surface are also visible.

This oblique view brings all the elements together. The bryozoan has closely encrusted the microtopography of the hardground surface. The Trypanites borings are shown cutting directly through the limestone of the hardground. Both of these observations confirm that the hardground was cemented seafloor sediment when the encrusters and borers occupied it.

This oblique view brings all the elements together. The bryozoan has closely encrusted the microtopography of the hardground surface. The Trypanites borings are shown cutting directly through the limestone of the hardground. Both of these observations confirm that the hardground was cemented seafloor sediment when the encrusters and borers occupied it.

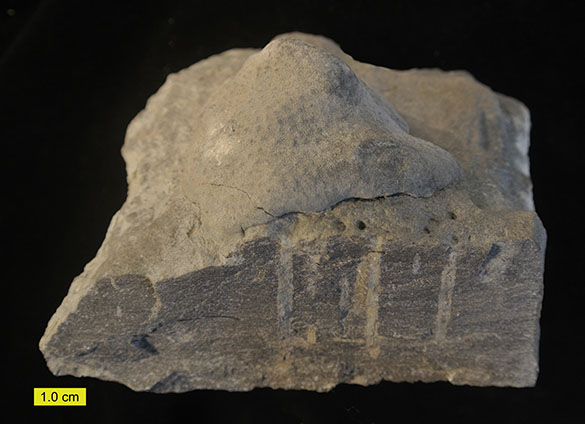

Here is a full cross-section view showing the borings and the draping nature of the bryozoan. Now for the twist — I’m showing the specimen upside-down! It was actually found in place with the bryozoan down, not up. This is the roof of a small cave on the Ordovician seafloor. The bryozoan was hanging down from the ceiling, and the boring organisms were drilling upwards. The true orientation of this specimen is thus —

Here is a full cross-section view showing the borings and the draping nature of the bryozoan. Now for the twist — I’m showing the specimen upside-down! It was actually found in place with the bryozoan down, not up. This is the roof of a small cave on the Ordovician seafloor. The bryozoan was hanging down from the ceiling, and the boring organisms were drilling upwards. The true orientation of this specimen is thus —

The cave was apparently formed after the carbonate hardground was cemented on the seafloor. Currents may have washed away unconsolidated muds underneath the hardground, forming a small cavity then occupied by the borers and the bryozoan: an ancient cave fauna. Brett & Liddell (1978) showed similar cavity encrustation in the Middle Ordovician, and I recorded a nearly identical situation in the Middle Jurassic of Utah (Wilson, 1998). Other detailed fossil marine caves are described from the Jurassic by Palmer & Fürsich (1974) and Taylor & Palmer (1994).

The cave was apparently formed after the carbonate hardground was cemented on the seafloor. Currents may have washed away unconsolidated muds underneath the hardground, forming a small cavity then occupied by the borers and the bryozoan: an ancient cave fauna. Brett & Liddell (1978) showed similar cavity encrustation in the Middle Ordovician, and I recorded a nearly identical situation in the Middle Jurassic of Utah (Wilson, 1998). Other detailed fossil marine caves are described from the Jurassic by Palmer & Fürsich (1974) and Taylor & Palmer (1994).

I should write up this Ordovician story someday!

References:

Brett, C.E. and Liddell, W.D. 1978. Preservation and paleoecology of a Middle Ordovician hardground community. Paleobiology 4: 329– 348.

Bromley, R.G. 1972. On some ichnotaxa in hard substrates, with a redefinition of Trypanites Mägdefrau. Paläontologische Zeitschrift 46: 93–98.

Palmer, T.J. 1982. Cambrian to Cretaceous changes in hardground communities. Lethaia 15: 309–323.

Palmer, T.J. and Fürsich, F.T. 1974. The ecology of a Middle Jurassic hardground and crevice fauna. Palaeontology 17: 507–524.

Taylor, P.D. and Palmer, T.J. 1994. Submarine caves in a Jurassic reef (La Rochelle, France) and the evolution of cave biotas. Naturwissenschaften 81: 357-360.

Taylor, P.D. and Wilson. M.A. 2003. Palaeoecology and evolution of marine hard substrate communities. Earth-Science Reviews 62: 1–103.

Wilson, M.A. 1998. Succession in a Jurassic marine cavity community and the evolution of cryptic marine faunas. Geology 26: 379-381.

Wilson, M.A. and Palmer, T.J. 1992. Hardgrounds and hardground faunas. University of Wales, Aberystwyth, Institute of Earth Studies Publications 9: 1–131.